What makes a life in art? What does it mean to pursue something with daily diligence and passion to an uncertain result? Art can be hard to measure in worldly terms. History may deliver a different verdict from the contemporary one.

It wasn’t long after I entered UCSB in 1957 as a 17-year-old freshman that I met Michael Dvortcsak. Mickey, as he was known, was probably the most vivid person I’d encountered. Though only a semester ahead of me, he seemed far advanced in this game of life I was trying to scope out. Witty, talented, athletic, charismatic, he lived in a trailer off the road from Goleta to Santa Barbara where he cooked, listened to music, studied, drew, played ukulele, and hosted girlfriends.

We soon became fast friends. But partly to placate my father’s hopes for me, I transferred to Stanford my sophomore year. My return to UCSB the following year probably had a lot to do with Mickey, who epitomized what Stanford lacked: inspiration, originality, unfettered imagination.

UCSB at that time was still little more than a collection of Quonset huts and administration buildings. Yet drawn by the twin allures of good weather and good salaries, a formidable array of elite educators had landed there, notably in the literature and art departments, inducing in us kids a heady mix of surfer hedonism and high seriousness.

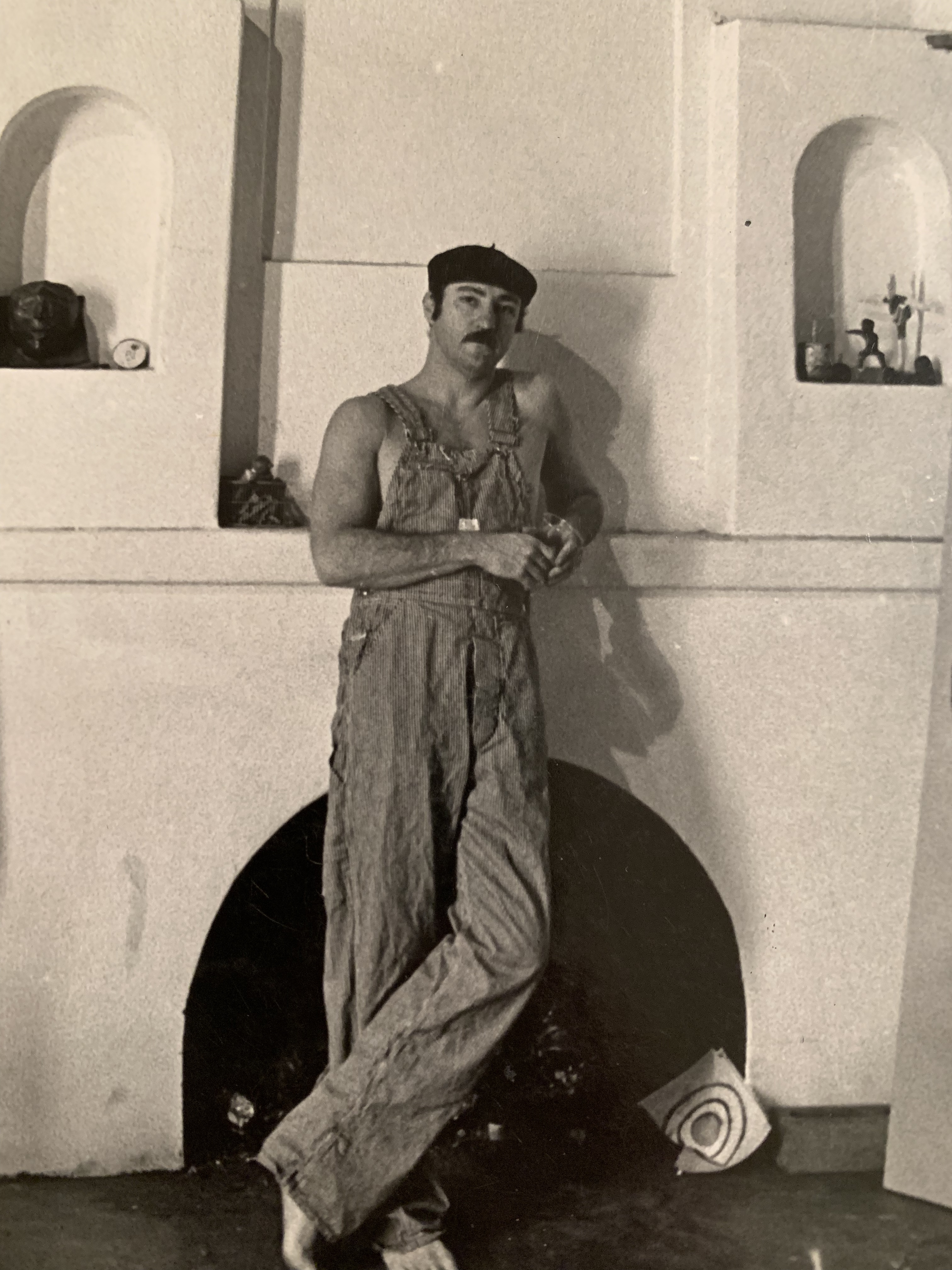

Mickey, who’d shown an early facility at drawing, was studying under the fiercely figurative tutelage of Howard Warshaw and the visiting Italian-American master Rico LeBrun. In the English Department, we sat in small seminars with the likes of Aldous Huxley and Christopher Isherwood.

Weekends we listened to early Ray Charles, drank beer, played volleyball, and compared notes on Caravaggio, Hermann Hesse, Art Blakey. Mickey was starting to draw attention outside UCSB as a young artist to watch, while I edited the school paper and drummed at a jazz club called The Spigot. There were lots of parties. Once, suspended from school for being at a gathering where alcohol was present, we spent the days playing frisbee at the beach.

After graduation, Mickey headed for Italy and the museums, me to Paris, Copenhagen, and Barcelona to work in jazz clubs while trying to write. We met up outside of Rome and lived together in Florence for a while, Mickey deepening his communion with the Renaissance masters.

Back in California, our lives diverged. He taught in the Art Department at UCSB, while I moved to San Francisco, then Los Angeles. We started families. At one point, enthused by new ideas running through California’s 1960s, we made a few experimental films together. I recollect a visit to Mickey in his large house on the Mesa and running into our roommate from UCSB, Richard Serra, on the brink of global fame as a sculptor.

After that, Mickey and I drifted out of touch. Word reached me that he no longer taught at UCSB. There had been a family tragedy, difficulties with alcohol. Once in 1984, our paths crossed in Manhattan. He had work in a show; I had a novel coming out. A few years later, we met in L.A. for an exhibit of his, Mickey entertaining as always but loud, off-key, a parody of my brilliant friend from youth. His painting, what I saw of it, seemed wooden, stalled. The drinking had overtaken him.

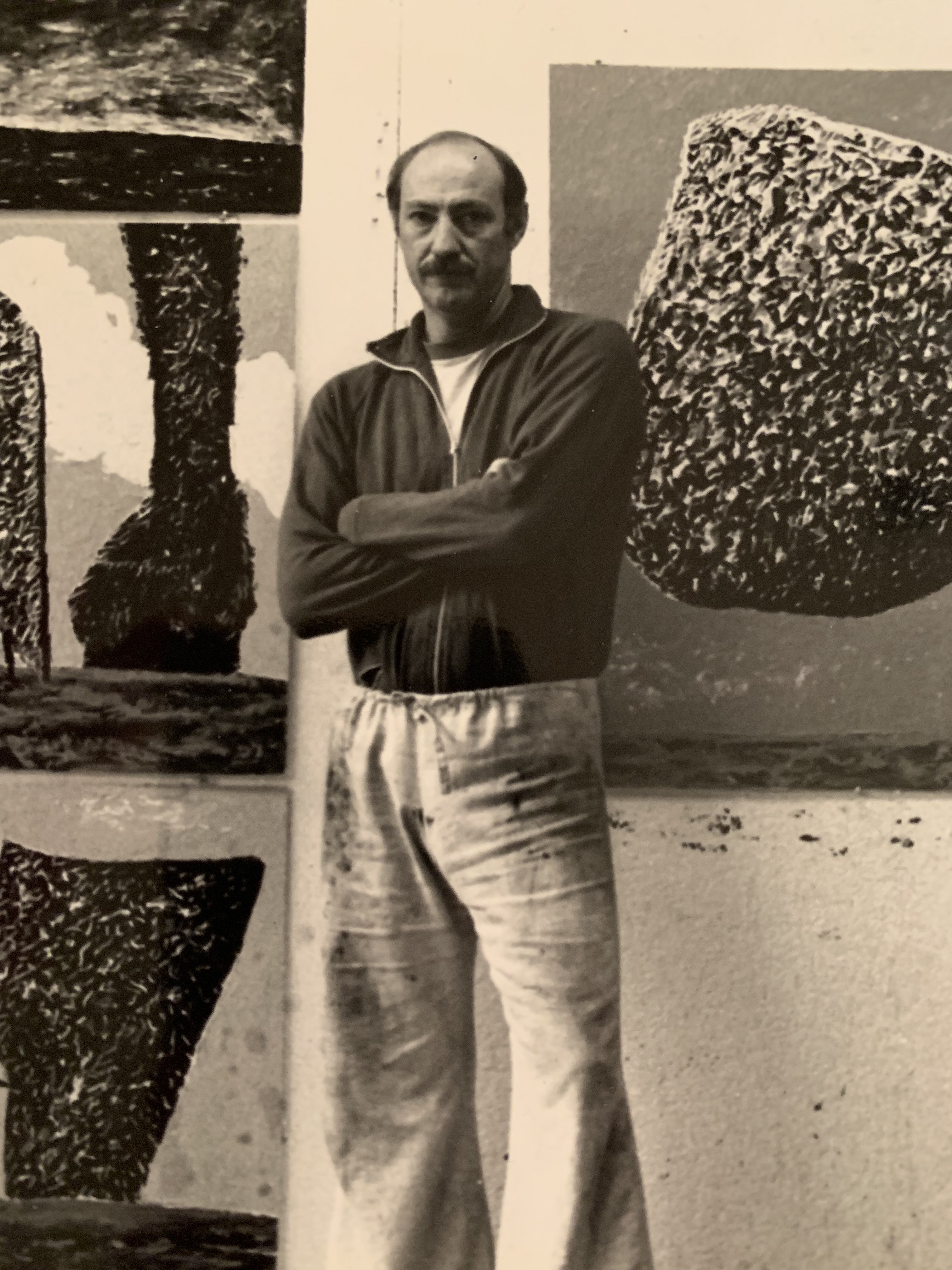

Toward the end of that decade, admittedly out of a sense of duty, I visited him at his studio in Ojai. There had been a recovery; he had come through. The man I encountered was sober, wise, spiritual.

He was painting daily, assiduously. The work was coming alive. Portraits. Studies. Figures. Landscapes. There followed shows, galleries, patrons, museums. A variety of recognitions. The rich respect of his peers. Visits from loyal friends, fellow artists.

Each day, Mickey got up and painted. This is a life in art; this is what you do. He would do it for the rest of his days.

Across Michael Dvortcsak’s lifetime, a good deal of art had moved off the canvas. Classical painting, that ancient pursuit, ceased to command the stage. Sometimes there were lean stretches. Yet Mickey remained steadfast. Once or twice a year I’d visit, and he’d make pasta; we’d maybe play a little piano, listen to Glenn Gould, talk of mutual friends. The visits were always warm, insightful. We’d laugh over the weirdness of growing up in Southern California in the 1950s, the peculiarities of aging.

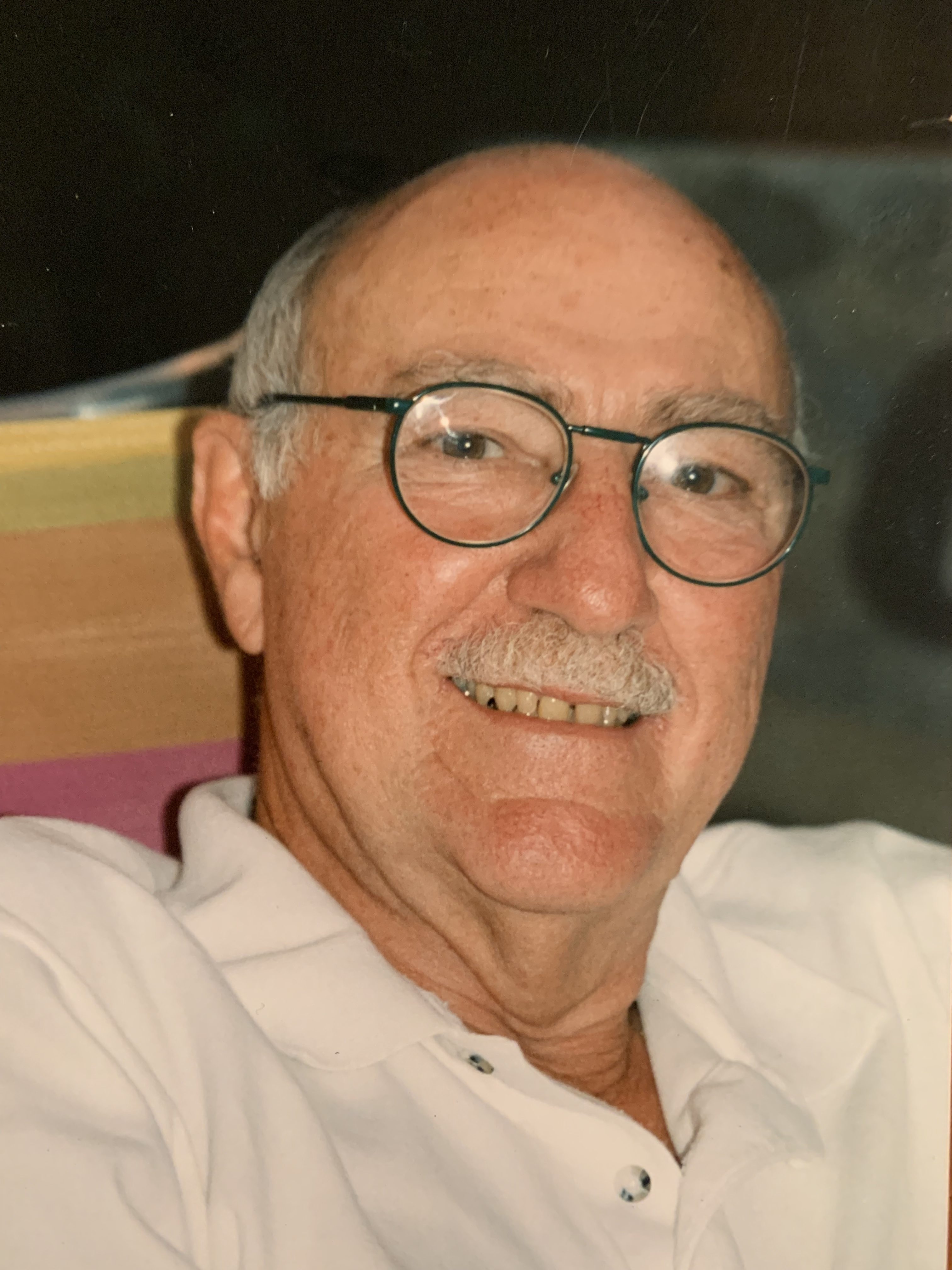

He became a lovely man, at peace with much, rich in art, children, and grandchildren.

Beginning in 2008, my friend’s lifelong conversation with art culminated in a striking new series, an homage to painting itself. Set in the world’s great museums, the artist looks at people looking at masterworks, which he has also rendered. A marvelous, magical hall of mirrors, summoning all his artistry and skills.

Michael Dvortcsak lived an exemplary life of devotion to his chosen creative art. He ventured far into the spiritual heart of things. He knew love and passion and friendship and family. How I’ll miss him.

A celebration of life for Mickey Dvortcsak will be held on January 25 in Ojai to share his art and his life with friends and family. To attend, please email alexeyd@gene.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.