Three Murders That Made Santa Barbara Shiver

Armenians and Greeks, Bullies and Editors, Teen Soldiers and Homeless

by Nick Welsh | Published October 31, 2019

Santa Barbara may be paradise, but its inhabitants have been killing each other in ways mundane and spectacular since the days of Adam and Eve. The three recounted here, however, hit us with their loud and obvious resonance with what’s happening today on the world stage and right here in Santa Barbara. The point being, the more things change, the more they don’t.

The Armenian Assassin

The Armenian Assassin

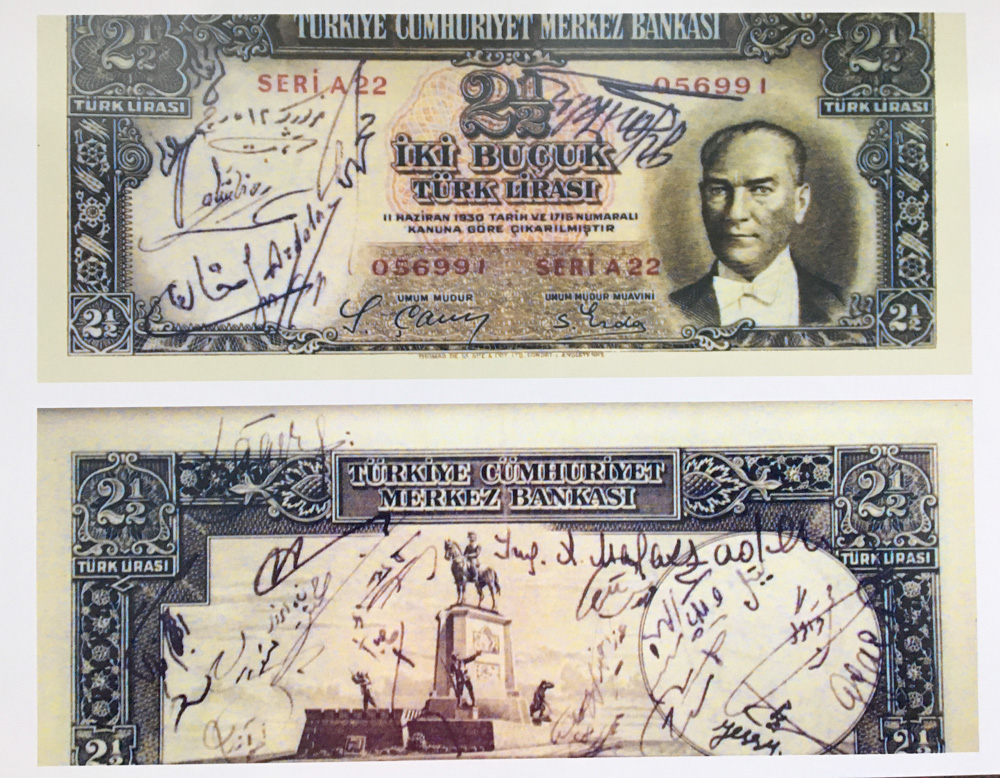

Gourgen Yanikian | Photo: David Minier

Gourgen Yanikian was in a big hurry. “Where have you been?” he asked the sheriff’s deputies when they showed up at the Biltmore Hotel to arrest him for the murder of two Turkish diplomats. “I’ve been waiting 30 minutes.” Actually, Yanikian had been waiting considerably longer than that.

At age 77, Yanikian was known to many in Santa Barbara as a retired civil engineer, folk-dance aficionado, and man about town — but the true story of his life had been written long ago in the blood of slaughtered Armenians. At age 8, he watched Turks slit the throat of his older brother. By 20, Yanikian had seen thousands of dead Armenians — 26 bodies were members of his own family.

After the murder of his brother, Yanikian’s family moved from their Armenian village, seeking refuge throughout the region. Yanikian studied engineering in Russia, built railroads in Iran, and, after World War II, moved to the United States, where he developed subdivisions, made money, lost money, wrote books, and then moved to Santa Barbara, where he strode through the streets, an imposing figure with long silver hair.

He had spent more than 20 years trying to make a Hollywood film depicting the Armenian genocide — three million dead, killed by the Turks in 1915. When funding for the movie deal collapsed — done in, it would turn out, by actions of the State Department and the Shah of Iran — Yanikian began searching for a Plan B. He finally settled on murder.

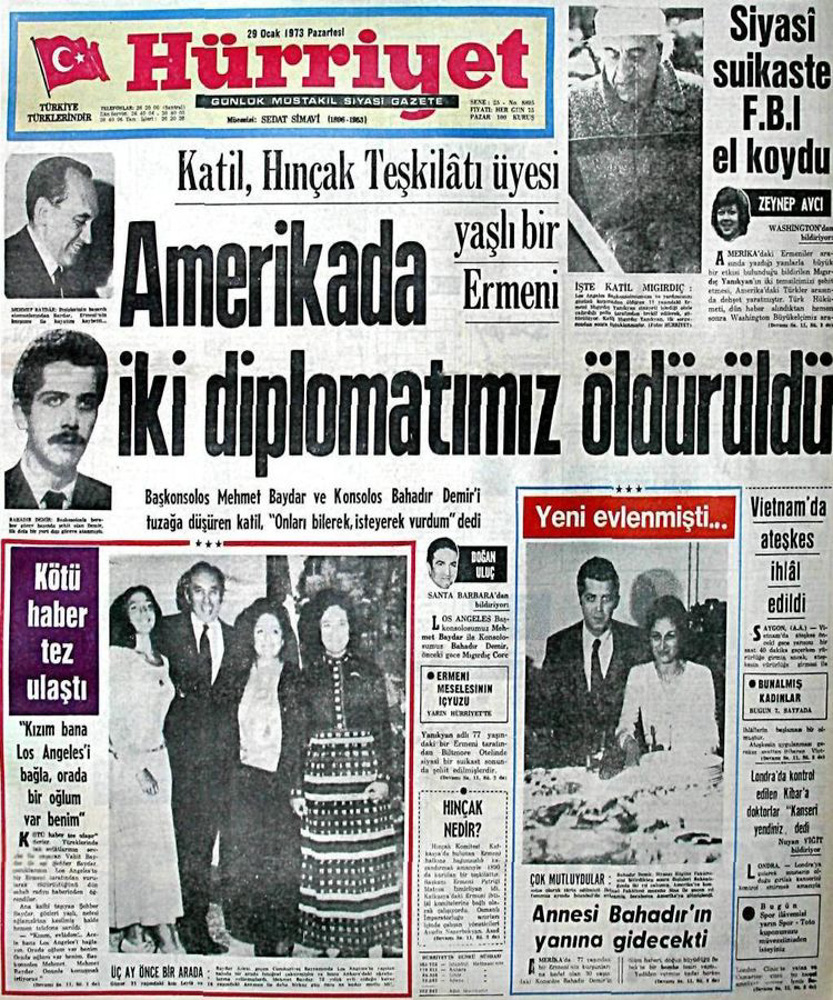

On January 27, 1973, in his Biltmore cottage, Yanikian sat down to lunch with two senior diplomats from the Turkish consulate. He had invited them to reclaim a painting stolen from the Turkish sultanate more than 100 years ago. Instead, Yanikian yanked out his Luger, secreted in a hollowed-out copy of Who’s Who in the West, and fired nine rounds at the diplomats. Realizing the men were still alive, he pulled out another handgun — a Browning — and shot both in the head twice.

He didn’t want them to suffer, he later testified, but he also told the jury, “I destroyed two evils. For me, they were not really human.” Yanikian’s plan was simple. By allowing himself to be arrested — he immediately reported the crime to the hotel’s front desk — he hoped his trial would become an international showcase convicting Turkey of crimes against humanity.

“Two million words I have written, and nobody pays attention,” Yanikian testified during his trial. “Maybe this is more noisy. Maybe this act will bring attention.”

It did, though not as he had thought. District Attorney David Minier blocked Yanikian’s efforts to call Armenian survivors and historians to testify. “Massacres do not form a defense,” Minier told the judge. “If they did, I could shoot a German delicatessen owner and have witnesses say I was justified.”

Minier later expressed regret over his tactics; Yanikian was guilty of murder, he wrote in editorials, but the genocide should have been acknowledged. For the first time in 35 years, Congress has just now passed a resolution acknowledging the genocide of the Armenians. It has yet to be approved by the Senate, however, and no vote—as yet—has been scheduled.

Murder weapon | Photo: David Minier

During his trial, Yanikian sought to represent himself as a philosopher king. Minier made him out to be a sleazeball, noting that Yanikian wrote a book detailing the sex lives of college coeds and that he tried to pick up a waitress two nights before the killings. Yanikian’s defense was diminished capacity brought on by the trauma he experienced as a genocide survivor. At the time of the killings, his wife, a doctor, had been suffering from severe dementia for seven years, and the once-wealthy family was now destitute.

Yanikian was found guilty of murder and received a life sentence. After serving nine years in prison, he was transferred to a care facility, a sick old man. At his Forest Lawn funeral, 350 Armenian rights activists gathered to honor his crime. “In our heart of hearts, we know he had not committed an act of murder,” one speaker proclaimed. “He committed an act of justice.

Soon after Yanikian’s conviction, 40 Turkish diplomats were gunned down around the world. The group who claimed responsibility for the murders called themselves the “Yanikian Commandos.”

The State Street Shooting

The State Street Shooting

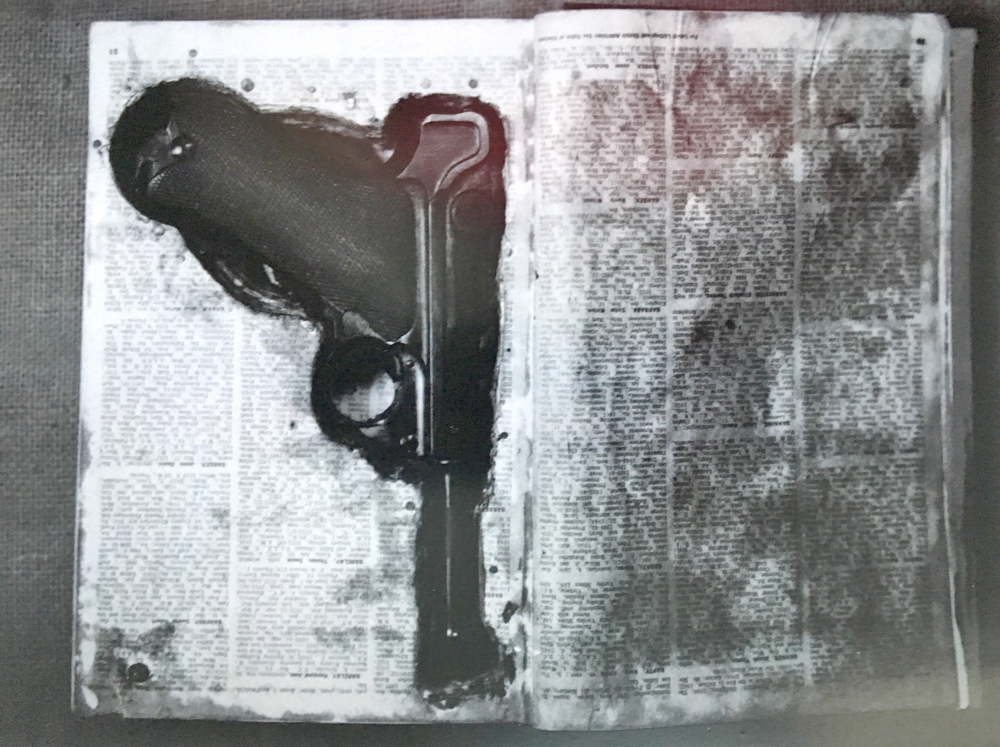

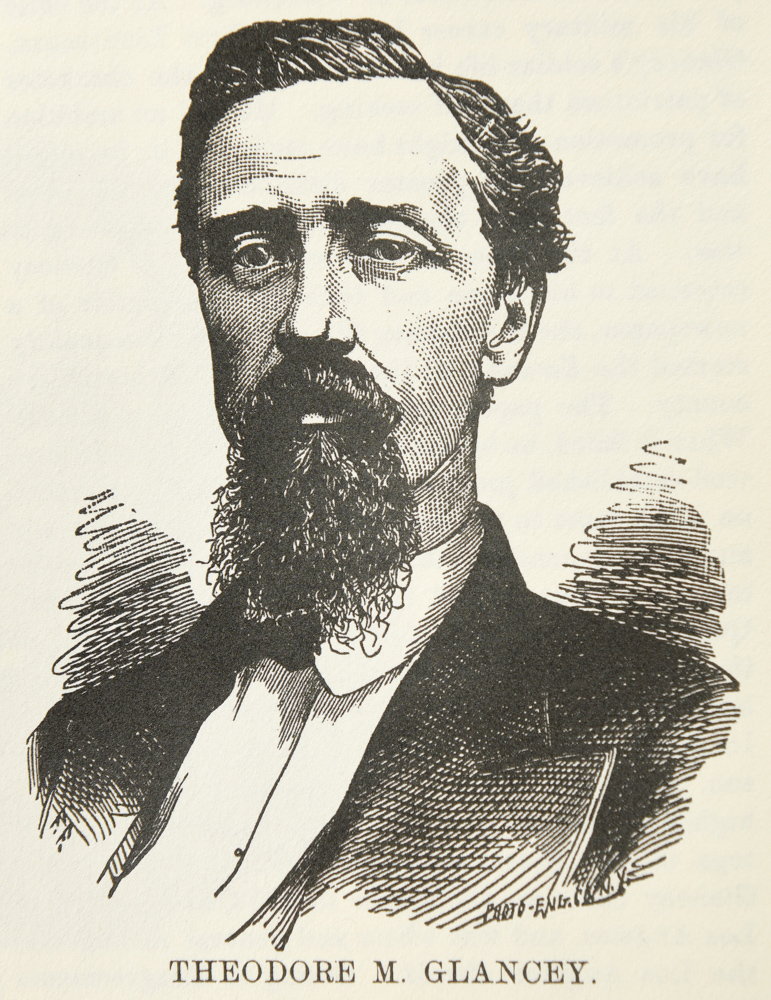

Theodore Glancey

Clarence Gray ranks as one of the great villains in Santa Barbara history, yet few people know his name. While a candidate, President Trump had bragged that he could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue and get away with it. In 1880, Gray — a charismatic, if frightening, force within Santa Barbara’s Republican Party — actually shot and killed the editor of the Santa Barbara Press in broad daylight on State Street. And he got away with it.

Theodore Glancey’s grave | Photo: Connie Anderson, Sonoma County, CA

When Gray moved to Santa Barbara in 1870, he was described as “reckless, unscrupulous, audacious, brilliant, enterprising, and witty.” An attorney by profession, Gray represented clients who were described as “gamblers, members of the sporting set, and habitués of saloons.” In less than 10 years, Gray himself was arrested more than 20 times, mostly for fighting. Once, he beat a priest senseless. When the Press newspaper offices were destroyed in an arson fire, Gray was the chief suspect, though no charges were ever filed. The paper — under a previous editor — had described Gray as “a blatherskite and brazen-faced demagogue and hoodlum.” In 1876, Gray beat up William Russell, editor of The Index, another publication, leaving his head a bloody mess. It was the fourth time Gray had assaulted Russell. He was fined $20.

Gray’s role in community life, however, was more complicated than his rap sheet might suggest. In 1873, Gray sought the Republican Party nomination for District Attorney and came within seven votes of winning. He was always an elected delegate at Republican Party conventions. In 1874, when Judge Pablo de la Guerra died, Gray was one of 12 pallbearers who carried the coffin through a crowd of 2,000 mourners.

In 1880, Gray again sought his party’s nomination for District Attorney. Again, there were horrified objections from the Press. When State Supreme Court stopped the election, Theodore Glancey, the new Press editor, celebrated: “The nomination was disgraceful in every respect,” he wrote, relieved that the “good people of Santa Barbara” would not endure the administration of justice by “hoodlums and law-breakers.”

Journalism at that time was not for the faint of heart, but there was nothing fainthearted about Glancey. He had just moved to Santa Barbara only a few years after the previous Press editor had been horsewhipped down State Street by the District Attorney, W.T. Wilson, and left in a state of “insensibility.”

Originally from Illinois, Glancey had the personality and physique of an ax handle. Described as “argumentatively gifted,” Glancey was a radical Republican, a strict abolitionist, and an even stricter teetotaler. His political reporting was said to be “terse, pointed, and fearless.”

Morris Hotel on Haley and State Street

In hindsight, it seems inevitable that Glancey and Gray would come to blows. On September 25, 1880, Gray confronted Glancey on State Street, demanding to know if he had written the article condemning his nomination. When Glancey said he had, Gray pulled out a pistol and tried to shoot him. Glancey grabbed his wrists, shouted he was unarmed, and walked away. Gray chased after him and shot him. The bullet struck one of Glancey’s wrists, broke both bones, entered his stomach, and blew a hole through him. Glancey stumbled into the Morris Hotel at State and Haley and collapsed in the reading room. He died the next day, lamenting: “I am dying without seeing my dear little wife-girl.”

Gray was tried three times on murder charges — but each time, he got off. The first trial ended with a hung jury. Despite many eyewitnesses, Gray claimed self-defense. The second trial ended in a conviction and a 20-year sentence, but the verdict was overturned when it came out that the jurors had sequestered themselves with 20 gallons of beer, three bottles of wine, and an indeterminate quantity of whiskey. The third trial proved the charm; Gray was flat-out acquitted.

Gray moved to San Francisco, but the cataclysmic fire of 1906 destroyed his health, and he died in Sacramento one year later.

Murder in the Gazebo

Murder in the Gazebo

The gazebo in Alameda park circa 1985 | Photo: Christopher Gardner

Michael Stephenson’s body was found in the gazebo at Alameda Park, where he had been stabbed 16 times and had his throat cut with sufficient force to sever his spinal cord. In life, Stephenson had made it past his 29th birthday.

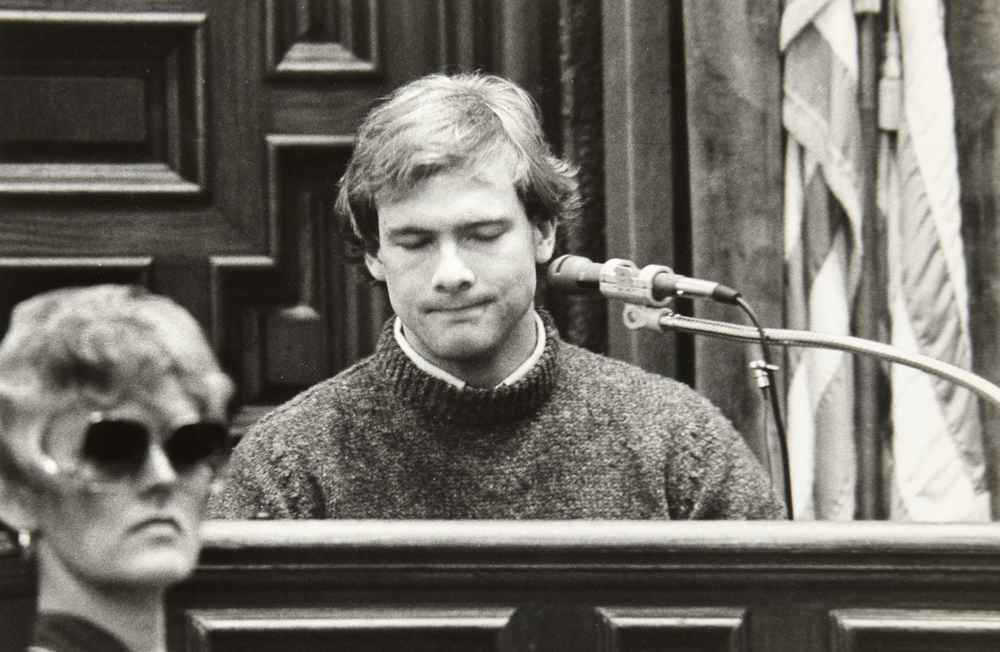

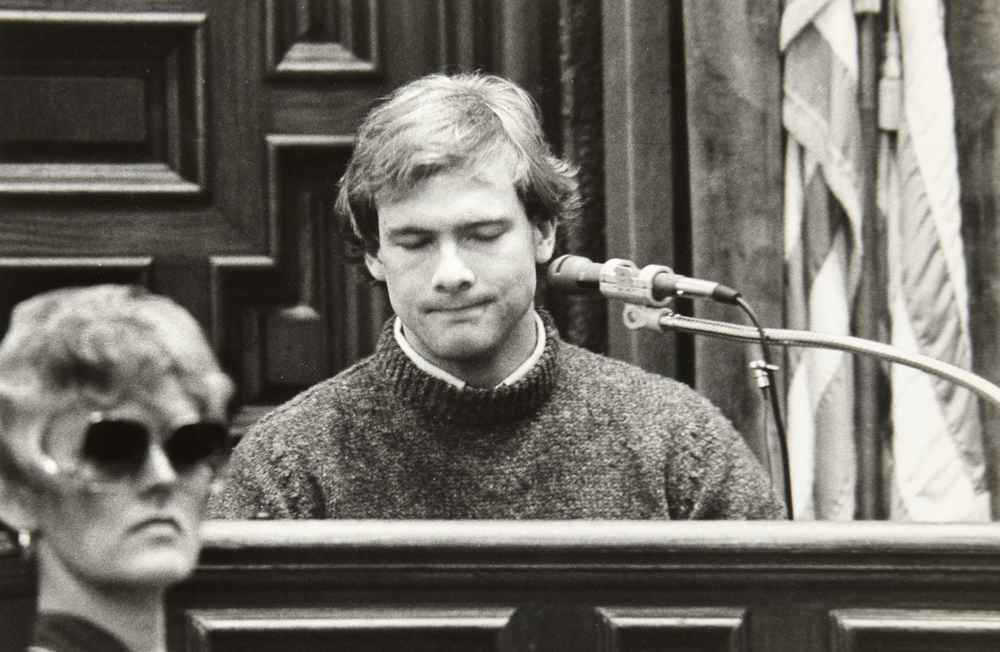

David Kurtzman | Photo: Christopher Gardner

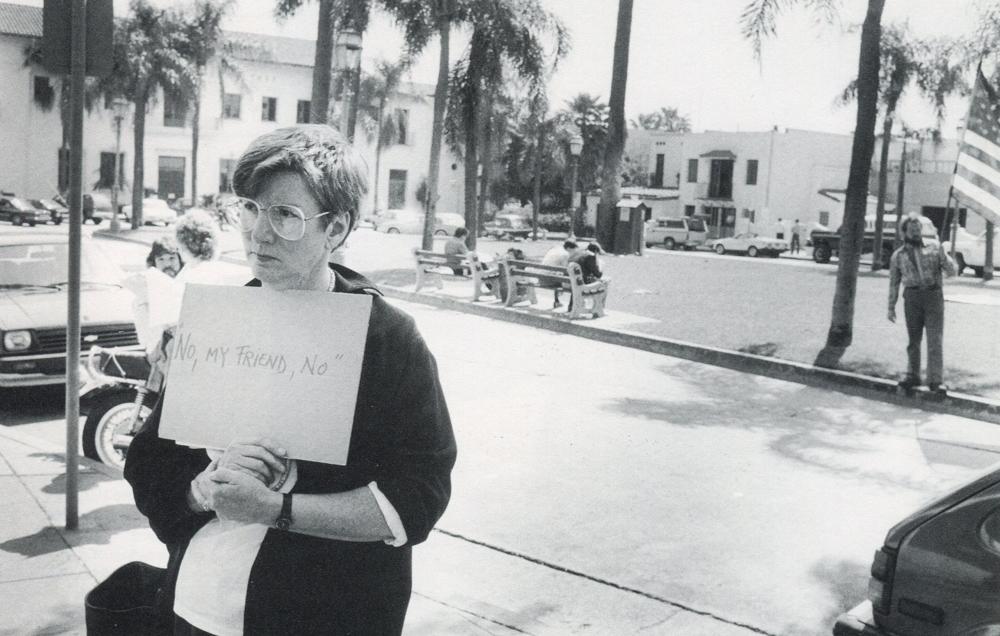

Blessed with a cheerful, open face and a mustache that would be the envy of any firefighter, Stephenson had been living rough in Santa Barbara for about three years. None of this mattered, however, on the evening of August 4, 1985, when Stephenson became the victim of the most lethal panic attack in Santa Barbara history. His last words reportedly were, “No, my friend.”

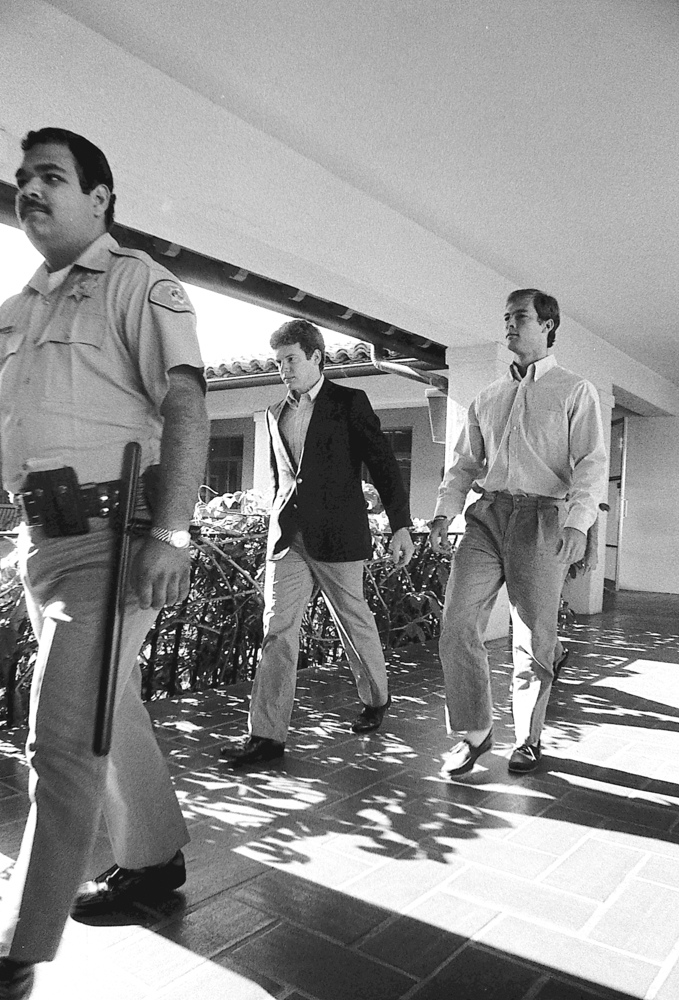

That night, Stephenson was in his sleeping bag on the floor of the gazebo, listening to music on his boom box, when two 17-year-old military prep school students — James Tramel and David Kurtzman — stumbled upon him. The young men were jacked out of their minds on adrenaline, testosterone, and hyperactive fantasies of revenge. Both came from messed-up families. Both were seeking admission to the national military academies West Point and the Air Force Academy. When they left their school on West Mission Street dressed in ninja black, they were on the hunt for Latino gang members who’d roughed up a schoolmate the previous night. Tramel thought to bring along Kurtzman’s 10-inch hunting knife, the blade blackened in the flame of a eucalyptus candle.

By all accounts, Tramel was the instigator. Charismatic and manipulative, he’d been conjuring schemes with a secret society he dubbed “The Nine.” He talked of building missiles and sodium bombs and trip wires. Before the two went on the prowl, another student asked him, “What are you going to do, kill someone?” He replied, “That’s the idea.”

James Tramel (left) and David Kurtzman | Photo: Christopher Gardner

As Tramel and Kurtzman entered Alameda Park, they thought they were following one of the gang members, but they quickly lost him in the dark. When they heard sounds from the gazebo, they went to investigate. Startled by the arrival of Tramel and Kurtzman, Stevenson sat up, startling Kurtzman. Words were exchanged. Then Kurtzman attacked. An Eagle Scout, he had told Tramel earlier that night that he knew about gutting a deer. But Tramel asked: “Have you ever killed a deer with your bare hands? Have you ever felt a knife go through a human head?”

In his confession, Kurtzman talked about flashes in his head, blood pulsing in his ears, and panic that gang members were crawling into the gazebo. “Panic,” his attorney later argued, “is simply not murder.”

On the witness stand, Tramel expressed shock and horror at Kurtzman’s sudden savagery. But when the two got back to their dorm, Tramel bragged to other students: “We bagged a Mexican.” When no one believed him, Tramel led them to the scene. The next morning, four of those students reported the crime to police, turning over the perpetrators’ bloodstained clothes as evidence.

It took a few days for the killing to seep into Santa Barbara’s collective consciousness. Fiesta was just around the corner, but a new hot-button issue had just landed in Santa Barbara.

President Ronald Reagan, who spent considerable time at his Refugio Canyon ranch, was being castigated for the class cruelty of his trickle-down economic policies. This put wealthy, beautiful Santa Barbara in the crosshairs of the emerging homeless rights movement. It focused on the city’s ordinance against camping or sleeping outside. The story got uglier when some local businesspeople were discovered pouring bleach on food discarded in dumpsters to discouraging homeless foraging.

National homeless rights advocate Mitch Snyder vowed to wage a massive civil disobedience campaign in the city. With philanthropist Kit Tremaine’s support, the homeless people of Santa Barbara became one of the best organized in the country. Soon De la Guerra Plaza was packed morning, noon, and night with homeless people and their supporters. It was national news when Santa Barbara lawyers won a case before the Supreme Court allowing those with no fixed abode to register to vote.

Photo: Kevin McKiernan

All this was just getting off the ground when Tramel and Kurtzman murdered Stephenson. That they intended to “bag a Mexican” became utterly beside the point. It was the murder of a homeless man in a city decried for its homeless laws in the county where the president lived. It was devastating. Soon buttons began appearing bearing the words: “Oh no, my friend, oh no.”

Ultimately, City Hall backed down on its ordinance. Tramel and Kurtzman were tried as adults, found guilty, and sent away for a long time. Tramel, ordained as an Episcopal minister while behind bars, was the first to get out after 21 years (Kurtzman served 26 years). His redemption was the stuff of much media coverage.