Graham Farrar: From Tech Geek to Santa Barbara Cannabis King

First Recreational Dispensary Opens on Mission Street

by Nick Welsh | Published August 22, 2019

G

raham Farrar might have been the classic all-American boy next door, the hardworking kid who mowed neighbors’ lawns in the afternoon and delivered their newspapers in the morning. He might even have grown up to become the doctor that both he and his parents thought he would.

Instead, Farrar — Goleta boy turned longtime Mesa resident — woke up this week to find himself sitting on top of the world. Ever since California voters approved the total legalization of cannabis in 2016, Farrar has been the most positive public face of Santa Barbara’s exploding industry.

Right now, Farrar is opening the first walk-in recreational cannabis dispensary in the City of Santa Barbara. Dubbed The Farmacy, it’s located near the intersection of Mission and De la Vina streets, next to Derf’s burgers, in the building where the city’s first and last video rental shop once operated. Standing in the parking lot, Farrar is delighting in the details: the red tiles, the wrought ironworks, the copper gutters. Less delightful are the bulletproof windows, the motion sensors, and the 18 security cameras. But finally it’s all come together. Though the city has issued two other recreational cannabis operations with retail permits, Farrar’s is the first one out of the gate.

This same week, Farrar survived an attempt by a formidable cadre of countywide cannabis critics to stop him from transforming a 350,000-square-foot Carpinteria flower greenhouse into a cannabis operation. But the County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously this Tuesday to uphold the project and deny an appeal by Carpinteria neighborhood activists upset about odors and possible health impacts (see News of the Week on page 9 for details). That vote should help, as should the 4-1 vote by the county’s Planning Commission in June. This would be Farrar’s second Carpinteria greenhouse. He’s already got a 150,000-square-foot greenhouse operating under the trade name Glass House Farms. Together he would have half a million square feet of cannabis plants under nonstop — nearly five harvests a year — climate-controlled cultivation.

Farrar jokes that only cannabis farmers talk in square feet. Other big-time ag operations are usually measured by acreage. This past month, Farrar entered that heavyweight ag world when he joined a 50-50 partnership with one of the most politically connected private water companies in California. If all goes according to plan, he will grow 9,600 acres of hemp in the Mojave Desert for the Cadiz Water Company. Hemp, virtually identical to cannabis, has strong CBD content needed for medicinal use, but low counts of the psychoactive compound THC. Only last year, the federal government listed it as a legal agricultural crop. Earlier this year, the State of California did the same. So these 9,600 acres on land owned by Cadiz qualifies Farrar and his Glass House Farms as very big time.

Hometown Boy Does Everything

In person, Farrar is built like a baseball player — sturdy, muscular, but not ostentatiously yoked. He gives off a deceptively accessible, laid-back vibe. Farrar wears black T-shirts, blue jeans, pukka shells around his neck, and a signature ball cap. Almost always. One cap has the Glass House Farms logo. Another reads “The Farmacy.” “My entire day is trying to make as many correct decisions as I can,” he explained. To reduce the potential for error, he figured, he needed to reduce the number of decisions. “What I’m going to wear is a decision I made once a while ago and don’t need to make each morning. And wearing a hat means I don’t have to wonder what my hair looks like.”

One of the things that sets Farrar apart from other pot farmers is that he actually enjoys the product. Or at least, he openly admits it. Some growers speak of how cannabis helped get loved ones through chemotherapy, but then quickly stress they personally don’t indulge. Farrar, by contrast, has been indulging since junior high school. Endowed with a self-confessed control-freak personality, Farrar uses it at the end of the day to cool his jets. “I don’t get baked, and I don’t use while working,” he said, but “I can sit on the couch and eat ice cream and watch a movie.” Farrar said he hopes his own two kids — ages 13 and 10 — don’t start as early as he did. But when they’re adults, he said, it’s up to them. “Throughout all human history, people have experimented with changing their consciousness,” he said. “They should have that right.” If people find themselves “going off the rails,” he argued, they should be reminded why the rails are there in the first place, not punished.

Another thing that sets Farrar apart from his fellow pot farmers is that he’s not really a farmer. Instead, he’s an unreconstructed tech geek and “serial entrepreneur” — the term he chooses — who just happens to do what farmers do. It’s a big difference.

Farrar and his parents moved to Santa Barbara in 1985 when Farrar was in the 3rd grade. They settled into a neighborhood between Goleta and Santa Barbara by Cathedral Oaks and Old San Marcos Road. His father, Lynn Farrar, worked as operations manager of the El Encanto hotel; his mother, Philippa Farrar, for Jordano’s. Farrar, who attended Foothill Elementary School, was an only child. His parents say he was “an inquisitive whirlwind,” a science geek, a focused reader, and sometimes preternaturally precocious. At age 11, Farrar negotiated a new phone contract for the family without his parents’ knowledge. It turned out he’d struck a really good deal. In 4th grade, Farrar would accidentally shoot himself in the hand with a BB gun. Surgery was required. Farrar demanded he not be knocked out so he could watch. Initially the doctor balked but eventually relented. By 7th grade, Farrar was enrolled in the Santa Barbara Middle School, where he discovered bicycles, computers, and friend Orion Barels, though not necessarily in that order of importance.

To say Farrar was drawn to computers is a criminal understatement. They were the black holes into which he was happily sucked. In no time, he could reassemble the motherboard of an Apple II. At S.B. Middle School, he became the school’s de facto IT assistant. By 7th grade, he was making $10 an hour as a freelance tech worker, helping people set up home computers back when such things were still technically challenging. Farrar embraced S.B. Middle School’s bicycle culture, and soon he could pedal as far away as Carpinteria to help clients get their computers working.

Tribal Elders

Successful entrepreneurs tend to be very smart or very lucky. Graham Farrar has been both. His friendship with Orion Barels — with whom he was inseparable from 6th grade through high school — was perhaps the biggest stroke of luck. Orion’s father, Larry Barels, founded WaveFront Technologies, which created the software necessary for the 3D animation since popularized by Pixar. He later cofounded, with John MacFarlane, Software.com, which allowed for the collection and delivery of email. Both companies would go public, WaveFront in 1994 and Software.com in 1999.

By that time, Farrar was all but a member of the Barels family. Barels senior took it upon himself to play the role of “tribal elder” where Farrar was concerned; to some extent, he still does. He says he saw in Farrar all the ingredients for great success. Barels hired him as a schoolkid at WaveFront and later at Software.com. And Farrar did not fail his expectations.

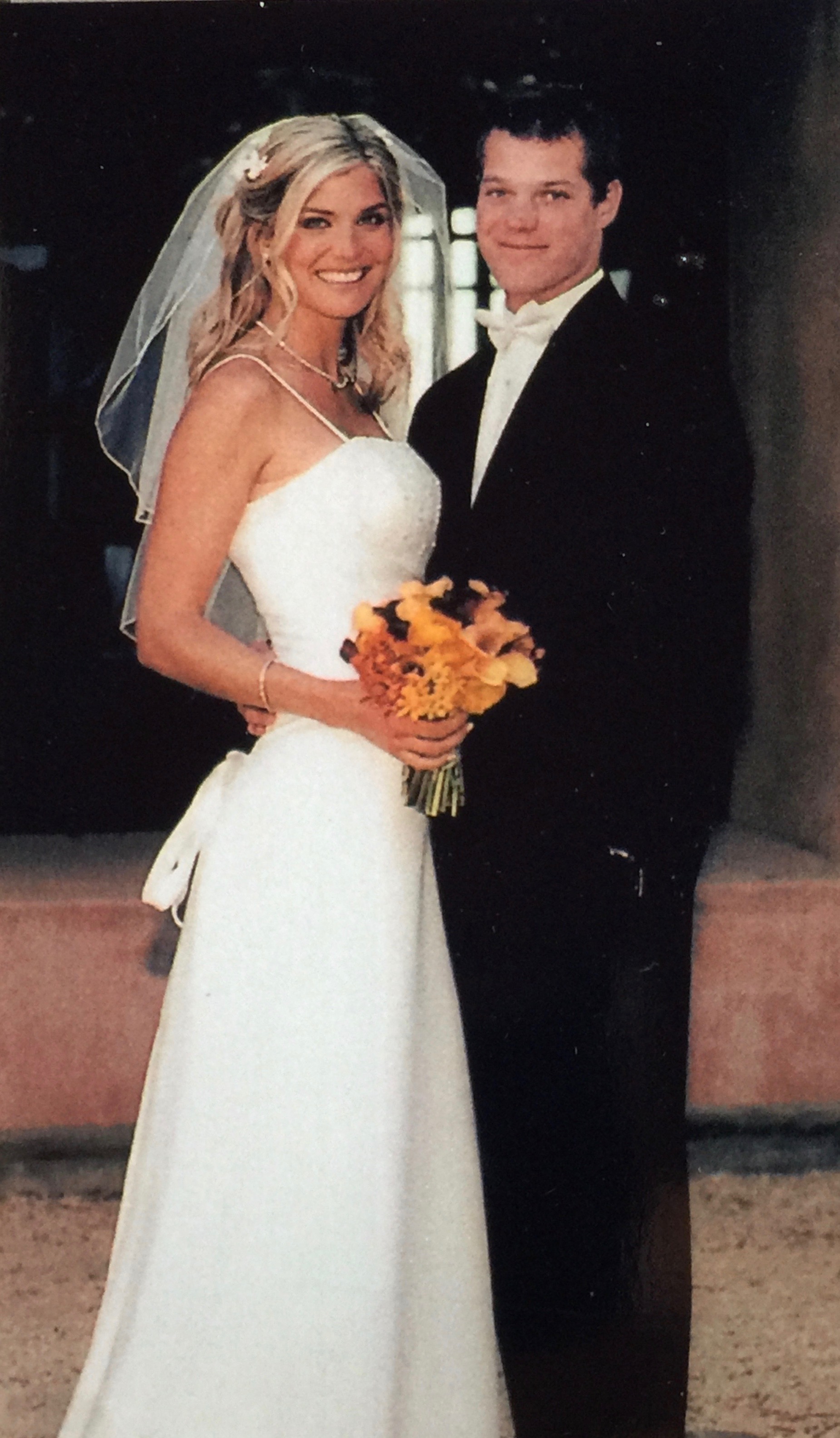

In high school, Farrar got Ds and Fs. High school, he said, was a waste of time. He dropped out, got a GED, enrolled at Santa Barbara City College, and gobbled up an intense load of hard-science classes. He signed up for the University of Colorado in Boulder, where he crafted his own specialized major in developmental molecular biology. That school, coincidentally, is where his parents had met. Also coincidentally, it’s where he would meet Sara Shaw — whom he would later marry — courtesy of an introduction by Orion Barels. Small world.

During summer break, Farrar worked at Software.com, skateboarding to work, his huge hair — not quite dreadlocks but close enough — billowing behind him. He installed a four-foot-long saltwater fish tank into his cubicle, but he wound up spending little time in the company of his fish.

Barels soon saw that young Farrar spoke as an equal with much older people — Pixar employees, Naval weapons researchers — who initially regarded him as a punk kid. But Farrar could back up his confidence with knowledge and results. He worked his ass to the bone. In one year, Farrar recalled, he traveled to 23 countries.

Barels and MacFarlane were conflicted about their young tech-geek stud muffin. Maybe he should go back to college. Farrar’s parents definitely thought he should. But in the dot-com world, there were no diagramed career paths. It was all made up on the fly.

So at age 17, Farrar was dispatched, along with MacFarlane, to New Jersey to provide support service to AT&T, the telephone giant. For Software.com, AT&T would be a mother lode that helped catapult the company to its eventual multibillion-dollar success. At the historic Bell Labs, Farrar’s job, as MacFarlane described it, “was to break the system.” He was replicating the most stressful demands that AT&T’s system could experience. By doing that, the company could engineer the necessary defenses to prevent the system’s total collapse.

Farrar didn’t merely work for these companies. He got in on the ground floor; he had stock. After WaveFront went public in 1994, Software.com went public five years later and Farrar sold some shares. Then 23, he bought a home on the Mesa, plus, for fun, a Ferrari and a 46-foot-long sailboat. “In my family, we didn’t have boats,” he said. His father liked to work on cars; Farrar remembers helping — if only sort of — his father sand blast a 1964 Mustang convertible. In other words, he had no idea how to sail. He took a course, and not long after, he and Sara embarked on a two-year sailing adventure that would ultimately take them across the Pacific all the way to New Zealand. “It’s hard to learn how to do without doing it,” Farrar would later explain.

Upon their return, Farrar joined another Santa Barbara company whose star was ascending — Sonos, the creator of networked home sound systems. He was the sixth employee the company hired. Farrar became Sonos’s troubleshooter, a service rep, and the guy who talked to product reviewers. Unlike many corporate spokespersons, Farrar learned how to argue his points without sounding argumentative, a talent that would serve him well in the cannabis industry.

As he and Sara had kids, Farrar stumbled onto other business ideas. For parents uneasy about doping their kids with the big screen, he created an interactive app — iStory — that offered a wealth of age-appropriate stories. Eventually he cashed out of Sonos, sold iStory, and went on another sailing adventure.

Budding Entrepreneur

The cannabis industry has always been alive and well in Santa Barbara, though completely illegal. With the passage of Proposition 215, which decriminalized medicinal marijuana throughout California in 1996, the industry became a legally nebulous, if vast, gray market. For a period, the Santa Barbara City Council — led by then-councilmember Das Williams — tried to permit, tax, and regulate retail storefronts for what were allegedly medicinal marijuana collectives. But a neighborhood backlash slowed the push toward regulation, and when Williams was elected to the State Assembly and moved to Sacramento, the industry went underground, dispensing its wares via a network of unregulated home-delivery services.

By 2014, the sale of recreational — now known as “adult-use” — cannabis was legal in the states of Colorado and Washington. The handwriting was on the wall; sooner or later, California would follow suit. The market was just too big, the tax revenues too irresistible.

By 2014, Farrar had started to focus on cannabis. He wasn’t cultivating yet, but he was supplying cultivators with yet another business venture, Elite Gardens, which tailored soil enrichment products specifically for cannabis crops. In 2015, the year Proposition 64 qualified for the November ballot, Farrar began cultivating cannabis in a greenhouse then owned by the members of Carpinteria’s storied Van Wingerden family. The “V-Dubs,” as they are known in cannabis circles, were famous for their efficient greenhouse flower operations. When competition from Colombia and Canada wiped out the cut-flower industry in the States, however, the V-Dubs cast about for a substitute crop. Though politically conservative, they embraced cannabis as the path to economic salvation. “Evolution” is the term family members use when addressing the county supervisors.

Deep-Pockets Guy

Farrar’s own evolution picked up serious steam when his path crossed with Kyle Kazan, a creatively aggressive real estate investor. Kazan is quick to tell you his life story: He played basketball for USC in the 1980s, worked as a special-education teacher in South Central Los Angeles, and then joined the Torrance Police Department in the 1990s. There, he witnessed firsthand what a colossal moral failure the war on drugs had been. “It’s been a war on the poor and on people of color,” he declared. “Second to slavery, it’s the worst thing that’s happened to this country.” Kazan left the Torrance PD in 1999 and became a spokesperson for Law Enforcement Against Prohibition.

By that time he had also learned the real estate trade. During the savings and loan crisis in the ’90s, over-leveraged banks and other financial institutions wanted to dump low-earning apartment complexes, but traditional loans were not available. This created what Kazan calls “a capital dislocation,” meaning not enough buyers for what’s being sold — or, in other words, a business opportunity. Beginning in 1996, when not working the graveyard shift at Torrance PD, Kazan began partnering with a hedge fund to buy up those properties cheap. He used his cop chops to rid the buildings of gang members and drug dealers. Based on media reports, tenants’ rights advocates have complained that Kazan also got rid of many law-abiding tenants, as well, by jacking up the rents. “Yes, there was a profit,” Kazan acknowledged. “But we cleaned up buildings that needed to be cleaned up, and we made a positive difference for the community.”

Kazan said he saw another massive “capital dislocation,” since conventional banks were terrified of investing in cannabis, which is still classified under federal law as an illegal narcotic. Into this yawning breach, Kazan brought to bear all the hedge fund dollars he could muster.

In 2015, Kazan was in Santa Barbara looking at a potential cannabis deal. One day he stumbled into Graham Farrar. The details are murky, but the outcome was a business success. “We hit it off immediately,” Farrar said.

It was Kazan and his investors who bought the greenhouse where Farrar has been growing 150,000 square feet of cannabis. It was Kazan who bought the 350,000-square-foot greenhouse that was the subject of this week’s appeal in front of the county supervisors. And it was Kazan and his investors who purchased the property where the new dispensary will operate. It’s this vast aquifer of relocated capital — courtesy of Kazan — that’s allowing Farrar to stay afloat as he goes through the expensive grind of the county’s review process. The exact details of the partnership are not clear, but Kazan and Farrar are part of a larger entity known as California Cannabis Enterprises, which also owns two other dispensaries, one in Santa Ana and another in Los Angeles. Both are chic and bright — a far cry aesthetically from what Farrar described as “the porn shop” vibe and “strip club location” of many dispensaries.

But it is Farrar who flies the cannabis flag at the County Board of Supervisors’ public hearings, many of which have been brutally long and acrimonious. Farrar has played a key role in Carpinteria’s cannabis growers trade group, has led the meet-and-greet charge, and, of all the growers, is the quickest to reply to reporters’ queries. One political consultant intimately familiar with county politics commented of Farrar, “You get the impression you’re watching a chess master at work, but who also manages to come across as a real human being, a real person. They’re not a whole lot of those out there. But you always wonder, ‘Yeah, but where’s the other side?’” For all his undeniable cyber smarts and charm, Farrar might have been a little too good for his own good.

Grassroots Resistance

The dramatic success that the cannabis industry has enjoyed thus far has engendered a relentless resistance among disparate grassroots groups. Farrar and others in the business have been tempted to dismiss these critics as nuevo prohibitionists motivated by moral qualms and change-phobic farmers who confuse the right to use pesticides with Santa Barbara’s agricultural “tradition.” In fact, the emergence of cannabis as a major new industry has generated serious growing pains that appear far from over. The opposition has now congealed into a countywide federation of likeminded discontents. They are outraged at what they see as the county’s acquiescence to the cannabis industry and have drawn to their cause the likes of multimillionaire philanthropist Sara Miller McCune, former 2nd District supervisor Janet Wolf’s administrative assistant Mary O’Gorman, award-winning investigative reporter Ann Louise Bardach, and noted environmental land-use attorneys Marc Chytilo and Jana Zimmer.

Cannabis growers are now engulfed in a food fight with the wine industry to the north and avocado farmers to the south. The stench of cannabis emanating from some of the 19 cannabis greenhouses that popped up along a four-mile stretch of road on the outskirts of Carpinteria have galvanized many critics. It may well be that the odor has diminished, as some insist, and that all the greenhouses are now equipped with odor-control systems. But these activists show little sign of going away and have vowed to appeal every single cannabis permit every step of the way.

As Farrar is quick to note, the relative footprint of cannabis is tiny — almost infinitesimal — compared to all other forms of agriculture. But Santa Barbara County still has the most land legally under cannabis cultivation of any county in the state. And California’s legal cannabis market — last clocked in at $3.1 billion — is by far the biggest in the world.

But again, success poses almost as many pitfalls for Farrar as failure. As a legal operator for whom state, county, and city taxes account for half his cost of production — Farrar is also at war with a black market that’s not just still thriving, but actually growing. The promise that Prop. 64 would help destroy the black market has thus far proved to be wishful thinking. Farrar claimed only 600 of the state’s 4,000 dispensaries were legally licensed. “That means 3,400 are technically black market,” he said. In Santa Barbara, two medicinally licensed, regulated home-delivery dispensaries have opened in the past year. Goleta has another two. But depending on whom one asks, there are anywhere from 10 to 26 unregulated home-delivery operations supplying the South Coast’s inextinguishable cannabis appetite.

Man in the Gorilla Suit

The battle over cannabis — its opportunities and its intrusions — will be endlessly relitigated until the county supervisors — and the regulators they control — get it right. By then, it will either be too late or irrelevant. In the meantime, it’s fair to say that Farrar’s success — and those of his fellow cannabis travelers in Carpinteria — have helped spark the political backlash that now threatens the political longevity of 1st District Supervisor Das Williams, who represents the Carpinteria Valley. Even as the county tightens the screws on noncompliant operators — 1.3 million plants destroyed, 42 tons of dry processed weed confiscated, and 36 warrants served — it will never be enough to make critics forget the chummy emails between Supervisor Williams and Farrar about going to a Santa Barbara Bowl concert together — they never did — or the thousands in campaign donations Farrar and his partners have made.

For someone like Farrar, one question remains: Why do this? He’s already been blessed by more success than most entrepreneurs experience. But in three of those deals — WaveFront, Software.com, and Sonos — Farrar helped bring to life someone else’s vision. This one is his. And it could be huge. Former politicians from both sides of the aisle are lobbying to allow interstate distribution — under current law, all cannabis grown in California must stay in California. Should that come to pass, any permitted operation in Santa Barbara County — where the sun shines 340 days a year and the mercury’s north of 70 for 320 — would be worth infinitely more than it is right now. And it’s already worth a lot. As Larry Barels put it, “In any situation, there are two gorilla, four chimpanzees, and 100 monkeys. What you don’t want is to be one of those monkeys. Right now, Graham looks like he’s on track to be something between a gorilla and a chimpanzee.”

What’s Inside the Farmacy, Santa Barbara’s First Recreational Cannabis Store

by Matt Kettmann

“The last video store in Santa Barbara is the first cannabis store,” explained Graham Farrar of The Farmacy, the recreational marijuana store he’s opening this week near the corner of Mission and De la Vina streets, in the former movie rental shop. Instead of piles of DVDs and Hollywood paraphernalia crowding a dim space, the Farmacy is bright with sunshine, cleanly minimalist in design, and full of friendly faces ready to help you find the weed you need.

“Our approach is a cannabis boutique — you could put jewelry in these cases and you wouldn’t have to change a thing,” said Farrar. “Pick up a box, handle it around — it’s regular retail now. It’s not the feeling of a pharmacist’s office.” (There’s even an original Chris Potter painting of Farrar’s Carpinteria greenhouse.)

After a greeter verifies you are 21 or older by checking your ID — which is mandatory for all ages, as they must also ensure shoppers do not go over the one-ounce-per-day state limit — you are free to wander the store. The open shelves and locked cases are loaded with 350 different cannabis-containing products, from 63 different types of flower — costing anywhere from $15 to $90 for an eighth of an ounce, or 3.5 grams — down to one brand of pot treats for your pet. There are edibles, extracts, lotions, tinctures, topicals, drinks, sublinguals, and culinary products, such as infused butter and olive oil. “And there’s lifestyle,” explained general manager Leia Cail. “There’s lube!”

The Farmacy team of 17 employees scoured the cannabis market to curate a wide range of their preferred brands, aiming to make it easier for customers to find something they want rather than be overwhelmed with options. “When you’re walking into a brand-new world, you don’t need the Walmart of weed,” said Farrar. “You want what your friend would recommend if you asked him.”

That includes a full section featuring Santa Barbara–grown cannabis from companies such as Glass House (which is also owned by Farrar) to Autumn Brands, Pacific Stone, and Raw Garden. “There was nowhere to buy anything from Santa Barbara County in Santa Barbara County until now,” said Farrar, confident that the farm-to-table ethos will translate to cannabis consumers.

He’s also excited about high-end products such as Field Extracts, which uses a fresh-frozen technique to cleanly extract cannabinoids into a pure resin. “Right now, everybody is drinking boxed wine,” said Farrar of what Santa Barbara aficionados have been missing without a legal pot shop. “They don’t know it, but right over here is Screaming Eagle.” (That’s one of the most expensive wines anywhere.)

Per state law, all of the products are subject to more scrutiny than almost any other consumer product. “Everything is tested,” said Farrar. “Each batch comes with a COA.” That certificate of analysis verifies that the product tested clean for an array of toxins, from fungus, bacteria, and bug parts to heavy metals and 66 pesticides.

The shop will be open 10 a.m.-8 p.m., seven days a week, with delivery services starting next month. Sales must be in cash or by debit card for now, with credit card processing coming soon. The Farmacy is also part of the Santa Barbara Axxess program, with 25 percent off for the first purchase and 10 percent off onward. The City of Santa Barbara will reap the 8.75 percent sales tax and special 6 percent cannabis tax on each purchase.

Later this year, The Farmacy will be joined by two other recreational cannabis stores in Santa Barbara: Coastal Dispensary, which is expected to open September 26, and Golden State Greens, for which there is no current timeline for opening.

Corrections: This story has been revised to state Farmacy is on Mission Street, not Milpas Street; the 350,000-square-foot greenhouse is outside the Coastal Zone and may not be appealed to the Coastal Commission; Prop. 64 qualified for the ballot in 2015; and Farrar purchased a home, Ferrari, and sailboat after selling Software.com shares.

You must be logged in to post a comment.