Communities Need Better Alternatives to Adapt to Wildfire

Don't Do the Wrong Thing for the Sake of Doing Something

In March, Governor Newsom issued an executive order waiving public input and environmental review for dozens of logging and vegetation clearance projects throughout the state, including three projects across 10,000 acres of chaparral habitat in Santa Barbara County.

The order — though well-intentioned — only focuses on habitat clearance while ignoring other methods that are more effective in protecting communities according to fire scientists.

To make matters worse, Governor Newsom’s budget revisions also reveal an alarming problem: no state funds are being dedicated to retrofitting existing homes with fire-safe materials, or “home hardening” as it’s often called. Scientists have long pointed toward the importance and effectiveness of retrofitting homes as the primary way to protect communities from wildfire.

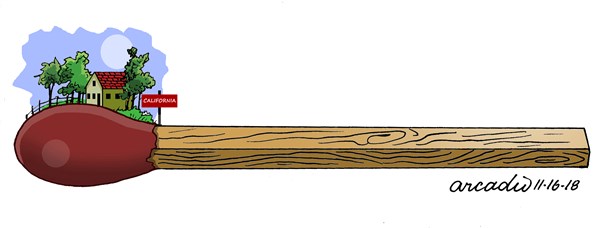

We all want to protect homes, neighborhoods, and people. But it’s important to understand that more homes are being lost to wildfires each year because flammable houses have been increasingly placed in fire-prone areas for decades, with more people than ever living in these high-risk areas. This dangerous sprawl has ramped up in recent decades, creating a recipe for disaster.

Just in Santa Barbara and Ventura Counties, approximately 1,150 new homes have been built in state-designated Very High Fire Hazard Severity Zones since the mid-1990s. And more people has meant more human-caused ignitions, whether through carelessness or transmission lines that produce sparks during extreme winds.

Yet, the governor isn’t working to address where homes are built and how existing homes can be retrofitted with fire-safe materials, opting instead to expedite timber harvesting and shrubland clearing. And since the projects exempted through his executive order aren’t undergoing any environmental review, the public has no ability to provide input concerning community safety and ecologically impactful activities.

Fire scientists at UCSB and across the western United States have called for a paradigm shift in how we think about wildfire and the risks it poses to communities. We need to treat wildfires during extreme conditions — the very conditions that will worsen with climate change — as we do other natural events such as earthquakes, hurricanes, tornadoes, and floods. Rather than try to control them, we need to adapt to them. We can look to other parts of the country to understand the importance of this adaptation.

In the Midwest’s “Tornado Alley,” people have learned to live on a landscape that can be impacted by a major tornado at any point during several months of the year. They build bunkers near their homes, place large community shelters in nearly every neighborhood, and employ an extensive tornado warning system so that few people are caught off guard. These natural disasters can occur suddenly with just minutes to prepare — something with which we’re becoming all too familiar when it comes to wildfires — yet there are relatively few deaths across tornado-prone areas each year.

Conversely, many cities in areas disposed to hurricane-induced flooding in the southeastern U.S. haven’t adapted as well. They continue to build structures on floodplains, build up levees that worsen downstream flooding and often fail, and try to outpace annually-rising floodwaters by building higher structural foundations. These areas in the Southeast are also where most tornado deaths occur each year as they haven’t yet adapted to the increasing number of tornadoes that have been shifting farther east over the past couple of decades.

California is currently at a crossroads between these two paths, and our decisions over the next few years will be important to say the least.

In January, the governor announced that California would spend $1 billion on habitat clearance projects over the next five years. Much of this will likely be spent in areas like Santa Barbara County that are dominated by chaparral — an ecosystem that isn’t suffering from unnatural fuel accumulation but rather an overabundance of human-caused fire that’s threatening the survival of chaparral in many areas. Clearing large swaths of vegetation won’t stop this trend and will in fact make it worse by spreading ignition-prone nonnative grasses and weeds.

Vegetation management does have its place, particularly immediately around homes. This is where scientists have found targeted vegetation modification to be most beneficial. Even more effective in saving structures, however, is ensuring that homes built before 2008 are retrofitted with fire-safe materials and that new homes aren’t placed in harm’s way. These are the approaches scientists say we need to be funding, but the governor just refused a proposal to appropriate $1 billion to crucial home hardening efforts.

Better alternatives to expedited habitat clearance projects that would help our communities truly adapt to wildfire are clearly on the table, but the state doesn’t seem to be seriously considering them. Why not?

We shouldn’t be doing the wrong thing for the sake of doing something. Our communities deserve better.

Bryant Baker is conservation director for Los Padres ForestWatch; Dan McCarter, president, Urban Creeks Council; Richard Halsey, director, California Chaparral Institute; and Chad Hanson, executive director, John Muir Project of Earth Island Institute.