The Last Perfect Place in California

Understanding the 24,000-Acre Dangermond Preserve’s High Hopes and Huge Hurdles

Story by Matt Kettmann & Keith Hamm | Published April 24, 2019

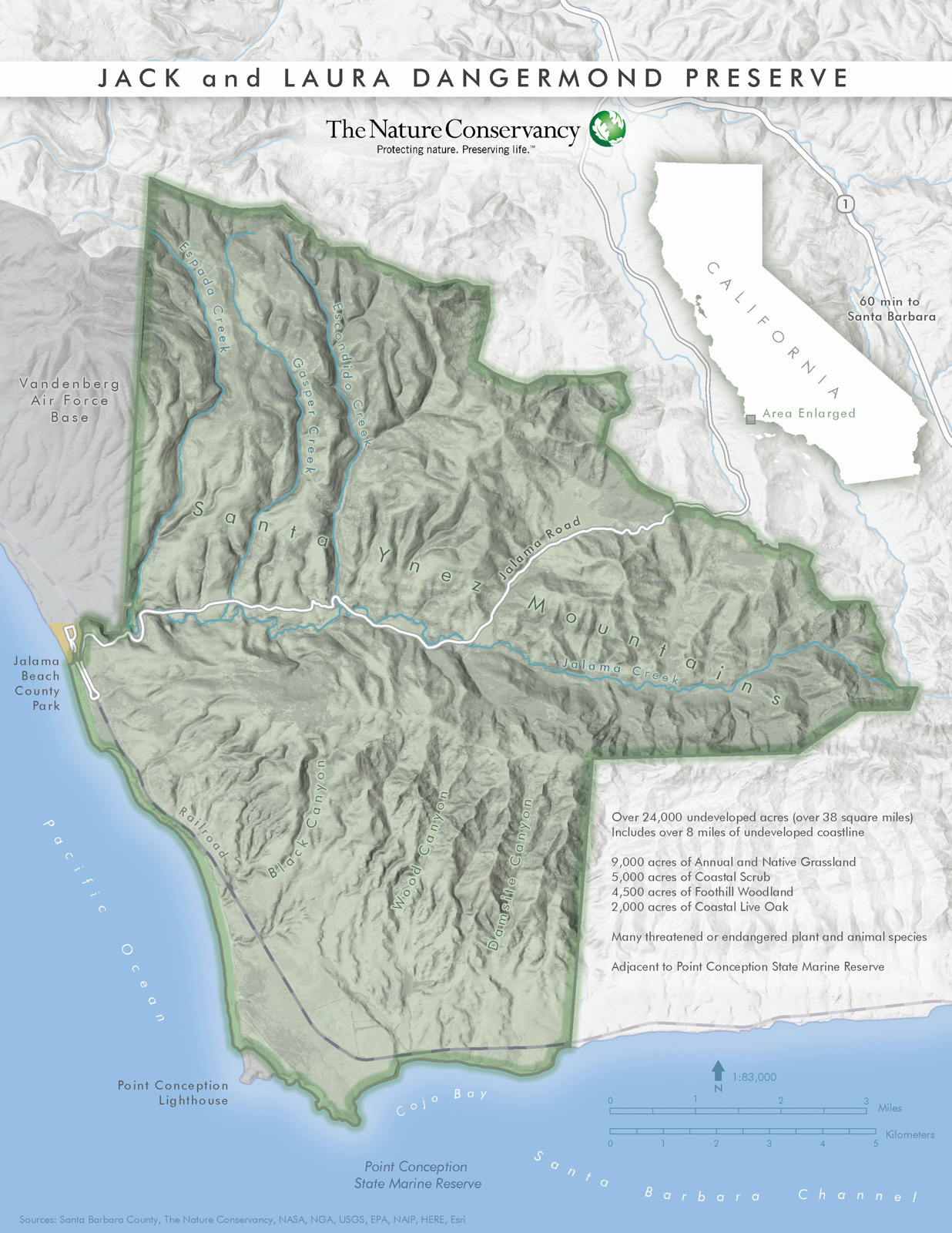

“The last perfect place” is what many are calling the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve, the nearly 25,000-acre property that the billionaire tech moguls saved with a $165-million donation to The Nature Conservancy in December 2017.

The land — which extends roughly from Vandenberg Air Force Base to Hollister Ranch and surrounds Jalama Beach County Park — was formerly known as the Bixby Ranch, when it was ruled by cattle for nearly a century, and the Cojo-Jalama Ranches, when developers resurrected the original Spanish names while waiting in the wings with grand plans. No matter what you call it, the nearly untouched property — about the size of the entire City of Santa Barbara — hugs California’s most prominent corner at Point Conception, where the lands and seas of the north meet those of the south.

Because of that unique geographic convergence, the preserve is an ecologist’s wonderland of biodiversity. Across its sprawling collection of oak woodlands, pine forests, coastal prairies, wetlands, and beaches live 14 threatened or endangered species, such as Lompoc yerba santa and the western snowy plover, and 54 “special status” species, including recently discovered populations of the tricolored blackbird, rarely seen along the coast.

More important than the numbers, though, is the entire equation. The preserve represents the last intact ecosystem for the Southern California coast, where even our protected areas are more focused on human recreation than ecosystem conservation. “This place is different,” is what ecologists say upon exploring the preserve. That’s according to The Nature Conservancy’s Michael Bell, who is the preserve’s director and played an integral role in saving the property, working toward that goal since the early 2000s.

“This is a place where mountain lions and bears still hunt and forage on the beach. They use their full natural habit, from the nearshore ocean to the beaches to the ridges,” explained Bell last week. “It’s an extraordinary system, and the observation and perspective of ecologists tends to be that it is the last of its kind. It is the last and best representation of a wild Southern California ecosystem.”

But it’s also drool-inducing for evolutionary scientists, as it represents a hotspot where evolution happened faster than elsewhere; environmental educators, who are already bringing classrooms out to explore the pristine nature; archaeologists, for the untold messages still buried by the untouched soils; and the Chumash people, who see the property as a chance to finally honor their sacred lands in the right way.

There is also a tremendous opportunity for science and research to be conducted in groundbreaking ways at the Dangermond Preserve. “This place belongs to science,” is what Jack Dangermond likes to say. So The Nature Conservancy and UCSB are teaming with Esri — the Dangermonds’ digital mapping company and the source of their wealth — on a groundbreaking partnership that will mandate an open data system for all who study there.

Rather than results getting lost by never being published — as the majority of scientific research projects are never published, according to Bell — or being culled to fit a paper’s argument, all of the information discovered by researchers will be available for everyone else to use from anywhere. “You’re aiming for a digital twin of the preserve,” said Bell.

The land, of course, is far from perfect. The property came with a number of restoration projects mandated by the California Coastal Commission — thanks to the previous owner’s unscrupulous and unpermitted activities — including the restoration of 200 acres of oak woodland, removal of 300 acres of ice plant, transfer of 36 acres to the county at Jalama Beach, and numerous other projects, all paperwork- and handiwork-heavy. Then there are bridge and culvert replacements, management of the cattle herds, security concerns, and … well, the work is just beginning.

But Bell dreams of a day, five years from now, when the preserve is fully functioning. A school group from Lompoc will come out for a weekend of backpacking, stay in the historic barn on Friday, and then hike a richly designed demonstration trail to the ridge camp on Saturday. By Sunday, they’ll be walking back along the beach, perhaps even checking out the Point Conception lighthouse thanks to partnerships with other organizations. And the entire time, they will be interacting with real scientists conducting research and proud volunteers working on restoration.

In so doing, the Dangermond Preserve won’t only be preserving a mostly lost past or capturing science for today, but also inspiring a more diverse class of scientists for the long tomorrow. Said Bell, referring to a scientific legend and one of Jack Dangermond’s close friends, “The next E.O. Wilson might come out of Lompoc.”

Q & A: Jack Dangermond Loves the California Coast

Half a century ago, Laura and Jack Dangermond fell in love with the California coast while honeymooning at Refugio State Beach. In the decades since, they built Esri, a pioneering digital-mapping company headquartered in San Bernardino County. The company’s products consume about half of the global market share of GIS, or geographic information system, technology.

Now billionaires, the Dangermonds are protecting the land- and seascape that provided a foundation for their deep appreciation of the natural world. In December 2017, their $165-million donation to The Nature Conservancy — the organization’s largest single donation ever — enabled the international nonprofit to buy the Cojo-Jalama Ranches, the 24,364 acres of coastal ranchland now called the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve.

As the dust settled after the historic acquisition last year, the Independent caught up with Jack via email.

How did you learn about the property and what made you decide to protect it? On our honeymoon 50 years ago, Laura and I drove and camped along the California coast. We were just kids but clearly realized what a special place this coastline was.

Some years ago, my brother, Pete Dangermond, a former state park director, told us about the Cojo and Jalama ranches. When we visited the property, we remembered our trip and also recognized it as a unique oak woodland and coastal ecosystem. There are many resources that include multiple plant and wildlife habitats and many important historic resources from the Native American, Spanish, and early California history.

While we were unable to acquire these ranches at the time, we kept trying and ultimately were successful with the collaboration of The Nature Conservancy. Being able to preserve the uniqueness of this place is a dream come true. It was a chance for us to protect an important coastal landscape in perpetuity.

Over the years, Laura and I have become deeply attached to this land. It is a very special place and one of the most unique land and ocean ecosystems in the world. It also happens to be the home to many globally important, rare, and endangered species.

Why are these places important to save? Natural areas, particularly pristine and intact areas like this one, are so important to us as humans, and they are disappearing. We did a study with Clark University, looking ahead 50 years, and mapped the natural areas. We found that in 50 years, the natural areas that remain will become very fragmented. The fundamental fabric of nature is being altered, and if we don’t act, these areas are going to disappear. A hundred years ago, we established a national parks system to protect the splendor of our lands, and it gives me a kind of solace to think that more of these kinds of areas will now be protected.

What’s your connection to the natural world? We live on an avocado farm in Redlands and go walking every day. My friend E.O. Wilson, a famed Harvard biologist, advanced the notion that people are bio-philiacs, meaning that we are drawn to nature even in unconscious ways, whether owning an aquarium or tending to planting. Laura and I feel connected to our living environment. We both enjoy experiencing the natural beauty of the world and the plants and animals within it.

My family’s business was a small nursery here in Redlands, California. My brothers and I all studied landscape architecture. As a landscape architect, I would like to see better [integration of] nature into cities as parks, trees, and open space. Laura and I have been active in our own community planting trees and helping organize community efforts to conserve land and develop parks. I think it is very important for us as humans to be connected to our natural world — connected near where we live, in parks and open spaces, and to also preserve large biologically important areas across our country.

Laura and I have always been passionate about conservation and doing our part to help protect our world and the special places within it. We fell in love with this area of the California coast many years ago and have long wanted to help preserve this area. We are so pleased to be working with The Nature Conservatory. This means that this special place will be owned and managed by the strongest conservation organization in the world.

Had you made a substantial donation to The Nature Conservancy before? Esri itself is very active in supporting conservation activities around the world and I would like to acknowledge our users and their staff for all the support and encouragement they have given us in our work over the years. Their collective efforts have not only helped conservation globally but have also enabled us to take this personal step to fund TNC.

With regards to our gift, this funding was done personally. However, Esri has donated our software and technical support to TNC for many years. This effort reflects the core values and mission of Esri.

How can your company technology help preserve the property? This project sets aside more than 24,000 acres, including eight miles of coastline, and preserves one of the finest, unspoiled natural treasures in California. The property surrounds Point Conception and is one of the last large tracts of undeveloped, intact coastal habitat remaining in California.

Laura and I are working with The Nature Conservatory in its efforts to determine how this preserve can best be managed for conservation and education. The Nature Conservatory, UCSB, and Esri will be working together to create a GIS system to monitor and model this unique landscape with the vision of creating a “digital twin” of this landscape for science, education, and management.

We believe it’s important to use science and technology to further land conservation around the world.

What’s your connection to UCSB? Esri has worked closely for many years with UC Santa Barbara’s Geography Department supporting student research in the field of geographic information systems (GIS) and its applications. They are the leading research and technical institution in this field, and we have hired many of their students.

Laura and I established an Endowed Chair in Geography [almost 10] years ago to support our interest in geography and its application to environmental and land-use problem solving. Our hope is our support encourages students to pursue careers rooted in spatial-analytic methods and GIS technology.

We [have established] a new UCSB chair in Environmental Conservation that will use the preserve as a living laboratory for landscape monitoring, analysis, and management techniques.

What message do you hope this donation sends to the public and perhaps other philanthropists? We hope that our gift inspires and motivates other people and organizations to pursue similar opportunities and conserve the important remaining natural areas that are so important to the future of our planet. There are lots of wealthy people in the tech industry and other industries in California and all over the world, but in fact, any of us can really make a difference.

I encourage everyone to look at how they help conserve special spaces in their own communities. What is that special place? Is it an abandoned lot that can be made into an urban garden? Is it a stream? It will take all of us working together, making our communities and world more sustainable and livable.

You must be logged in to post a comment.