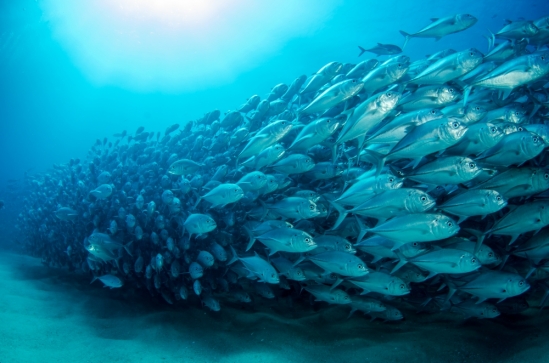

Rising temperatures are affecting ocean fisheries several papers have documented recently, including one authored in chief by UCSB postdoc Christopher Free. While at Rutgers University, Free researched populations of 124 species of fish in 38 oceanic regions between 1930 and 2010. While four percent increased in number in the warming waters, double that percentage suffered losses, according to the Science article published on March 1. Free is currently a quantitative ecologist with UCSB’s Sustainable Fisheries Group.

As could be expected, the upper ocean is warming the fastest, with the rate of change speeding up in the past two decades, according to a January 2019 report in Science. The ocean is absorbing about 93 percent of the heat being trapped by greenhouse gases, feeding tropical storms and developing an acidity that wreaks havoc on shellfish and their larvae.

In Free’s study, the effect of temperature rise on fish was found to vary by region: In East Asia, fish stocks declined by 15-36 percent as the waters warmed. “We were surprised how strongly fish populations around the world have already been affected by warming,” he told UCSB’s The Current. “Among the populations we studied, the climate ‘losers’ outweigh the climate ‘winners.’” Other negatively affected regions were the Sea of Japan, North Sea, and Iberian coast. On the other hand, the warmer waters improved the fishing in the Labrador-Newfoundland region, Indian Ocean, and northeastern United States.

Just as land dwellers experience heat waves, so do those in the ocean. Areas of the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian oceans were found to be particularly vulnerable to “marine heat waves” in a Nature report issued in March. Those areas have a great mix of species, or biodiversity, many of which are living at the edge of their warm range; they also see a lot of fishing activity or pollution. Baseline ocean temperatures were rising, but so were marine heat waves, by as much as 34 percent more often and lasting 17 percent longer.

An analysis of the Nature report in the New York Times noted that when habitats or “foundational species” like corals, sea grass, and kelp died, the vertebrates and invertebrates they sheltered vanished, too. Seabirds were subsequently affected. The researchers conclude that the oceans will warm as long as anthropogenic, or man-made, warming continues, and that fishermen, who feed billions of people, will be chasing fewer fish as they move to cooler waters.