A Footbridge Too Far?

The Public Requests a Footbridge to the UCSB North Campus Open Space

At its last meeting, the California Coastal Commission spent a large part of a day considering the case of Dr. Warren Lent. Dr. Lent has a house on the Pacific Coast Highway in Malibu. Adjacent to the house there is a public access to the beach, which Dr. Lent has kept barred with a locked gate. A lobster fisherman told the commission that, because of this, he has to walk a mile or so along the beach to reach the best location for lobster fishing, which he claimed is close to Dr. Lent’s house. The commissioners then debated among themselves for a considerable time what punishment to impose on Dr. Lent, eventually settling on a $4.2 million dollar fine.

Bear with me.

They then went on to consider the UCSB NCOS (North Campus Open Space) project. I had asked the commission, on behalf of local residents, to require the university to build a footbridge as a condition for approval of the project. This footbridge would allow local residents to continue to have direct access to the open space, as they have enjoyed for the past 50 years; 165 of them signed a petition in support.

The current direct access distance is about 50 yards. The university says that the two routes that will be available when the NCOS project is completed, the shorter of which is over half a mile, are “adequate alternatives.”

The parallel with the Lent case is obvious. But it was lost on the Coastal Commission, which summarily dismissed my request without discussion.

So what exactly is the NCOS project?

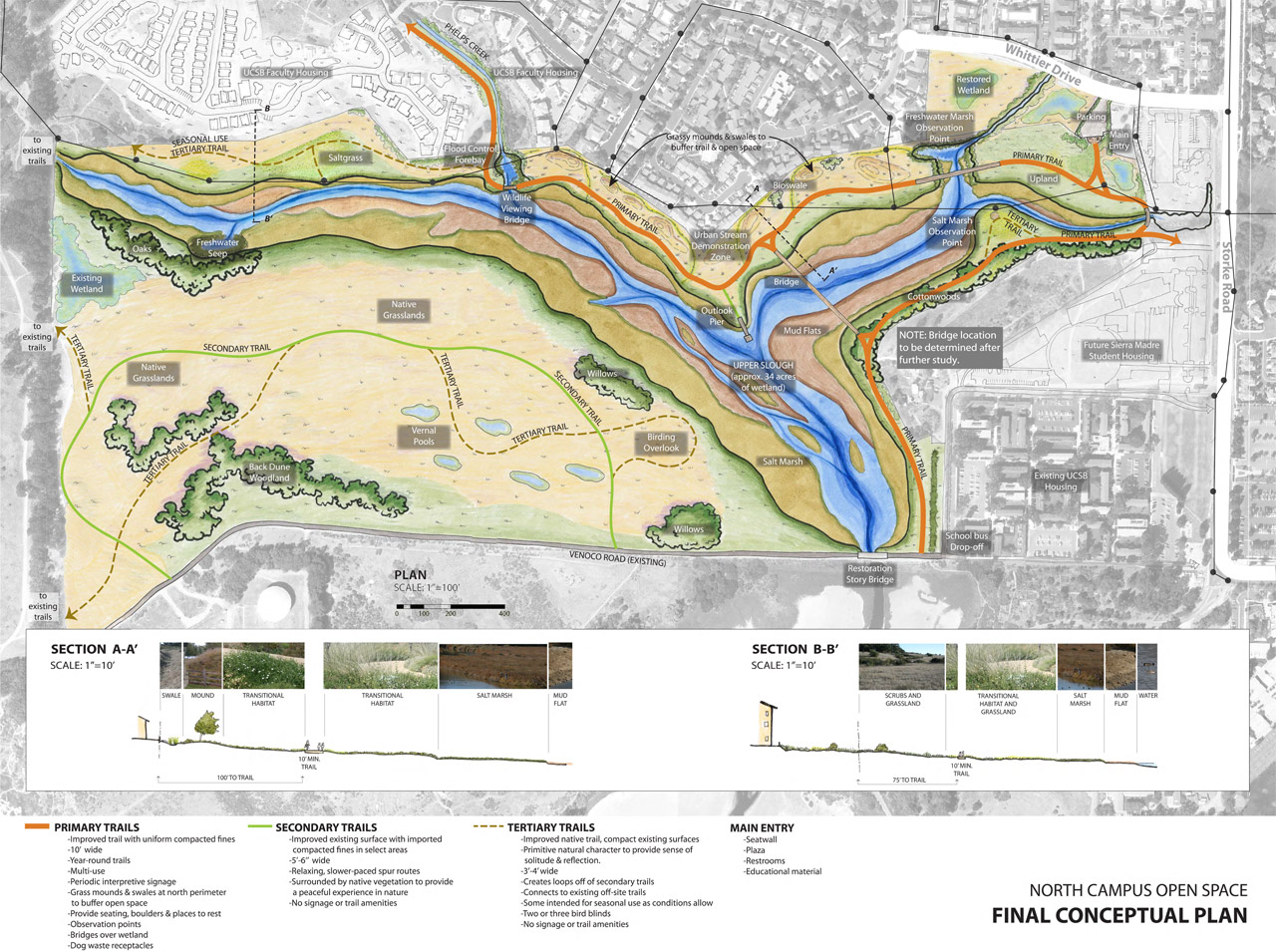

The project aims to restore the Devereux Slough, just west of Isla Vista, to its state before its upper reaches were filled in to create the Ocean Meadows golf course 50 years ago. It became possible after the Trust for Public Land acquired the golf course and gave it to the university, allowing the university to merge the land with the adjacent land to the south which it already owned (the “South Parcel”). This has created an “Open Space” which, together with the Coal Oil Point Reserve, now encompasses the whole of the Devereux Slough and the creeks that drain into it. The project will involve massive landscape engineering in order to reestablish the two arms of the slough, which originally ran east and west along the length of the golf course.

But this will cut off all direct access to the Open Space, since the entire residential area of West Goleta lies to the north of these creeks. The simple solution is a footbridge, and the obvious location for it is at the southern end of the Phelps Creek trail, where all the local residents cross now.

Yet the university has so far resolutely refused to include such a footbridge in its plan. It claims that a footbridge would cause environmental disturbance. But the plan already includes a much more substantial bridge over the east creek: a steel girder construction 300 feet long and 12 feet wide, whose only and obvious function is to provide a shortcut for commuters biking between the new university housing and the university campus. It will not provide any access to the open space.

In contrast, this is the only function of the proposed footbridge. And it is hard to see how a small pedestrians-only bridge could cause more environmental disturbance than a much larger structure with bikes trundling across it day and night.

So why is the university so resolutely opposed to this footbridge? The obvious reason is the cost. But curiously — and perhaps significantly — cost has not been prominent in the university’s arguments. Further, the vehemence of its objections, and the increasingly irrational and uninformed nature of them, suggests some deeper motivation.

Unfortunately it is hard not to conclude that a fundamental objective of the project is to minimize public access to the Open Space. As further evidence of this, each new revision of the project plan has included fewer internal trails: in the latest revision, there remains only one. And in the Coal Oil Point Preserve, all internal trails were physically obliterated several years ago.

If this is truly the intention of the university, it is utterly in breach of the spirit if not the letter of the constraints imposed on it by the Trust for Public Lands when it gave the former golf course to the university “for public recreation and enjoyment.”

And by its refusal to intervene in this case, the California Coastal Commission has totally failed in its mandate to “maintain and improve public access to the Coast and Coastal Lands.”

So, short of legal action, there now appears to be no remedy for the major loss of amenity that local people are about to suffer.

(For more information, visit www.change.org and search on “UCSB footbridge.”)