Grunt’s-Eye View of Afghanistan

Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger Reveal Real War in Restrepo

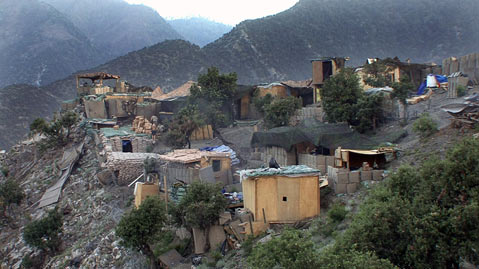

If war is hell, then the new documentary Restrepo brings us civilians closer than ever to the fire. Compiled from 150 hours of footage shot between June 2007 and August 2008 by photographer Tim Hetherington and writer Sebastian Junger in Afghanistan’s notoriously nasty Korengal Valley, Restrepo gives a “grunt’s-eye” look at the soldiers and their battleground, complete with all the sadness, fear, silliness, and stress inherent to daily firefights and constant threats of ambush. Avoiding the politics and talking heads of most war docs, Restrepo — named for a fallen medic and the outpost proudly erected in his memory — is solidly a soldier’s tale, from the excitement of arriving in a warzone and rush of the weaponry to the despair of fallen comrades and nightmares that stay long after leaving.

A British photographer who started his career shooting the wars of West Africa in the mid-1990s, Hetherington has recently won international accolades for both his still photography and his broadcast work in Afghanistan, and was happy to see Restrepo be named best documentary at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year. Hetherington spoke with the Independent earlier this week. What follows is an edited version of that conversation.

Did you know how hot the Kolengal Valley would be?

I was prepared because I had worked in many warzones before, but I wasn’t prepared because, like the rest of the world, everyone was very focused on Iraq. I thought Afghanistan was a peacekeeping operation. I went in thinking that we’d be walking around the mountains, drinking tea with elders, and occasionally getting shot at. But when we arrived, it was clear that the war had slipped out of control.

Did you fear for your life during that ambush?

I broke my leg during Operation Rock Avalanche, so that was a pretty intense time for me. It was after the American lines had been overrun, and there was a blood trail that ran down to a village. That night, we went toward the village for an early morning raid, and on the way down I broke my leg.

Did you have any preconceived notions about the soldiers going in?

It was my first time with the American army, so my preconceived notion was that I was going to be heavily censored. I had come out of that era of the previous administration where there was this idea that the embed system was control of the press by the military. … But in fact, we were not ever asked to show material, never told what I could and could not put in the film.

The other surprise was how close I got to the soldiers while embedded. … We spent 10 months with the soldiers. Usually, a journalist spends three weeks with soldiers and then never sees them again, so that relationship is tenuous, and you’re not able to get under the veneer very much. At first our soldiers were standoffish, but we spent so long with them that we developed this kind of intimacy, and we embraced the embed system beyond what it was designed for. The military didn’t expect us to get that amount of time with a group of soldiers.

What has the response been from the soldiers?

The military respects the film because they see it as being an honest portrayal of war. In it, they see their own experience, so the soldiers have reacted very well. Soldiers are very critical of the portrayal of war, especially with network news giving two to three minutes of political analysis. But that never brings in the reality of the ground in terms of the dirt and the grit. Our film gives you the grunt’s-eye view, so I think the military respects it.

Was this level of access hard to get?

We just kind of slipped out of the bureaucratic control of the military. We were far from Bagram. We were far from Jalalabad. Once we passed through those places, they forgot about us.

And we first went in 2007, when the world was focused on Iraq. The military on the ground in Afghanistan felt unloved and neglected. What you see in Restrepo is counterinsurgency on the cheap. … It’s like camping with guns. The military wanted the Department of Defense to know what was happening in Afghanistan. We certainly raised eyebrows when people started to see the film.

Did you ever find yourselves getting in the way?

Not really. We just kind of integrated ourselves into the platoon. We almost, for all intents and purposes, became part of the platoon. I had my place in the line. I knew where to stand. The soldiers knew we could handle ourselves in combat situations. We didn’t put them in danger and we didn’t get in their way.

The film shows progress being stalled at every level, with the Americans trying to work on big picture projects and the Afghans focused on day-to-day realities. Will they ever work together?

Two things, as far as commentary on the war; the first is that Afghans are a very practical people, especially the Korengalis. Winning hearts and minds isn’t about giving a bear hug or a high-five. Winning hearts and minds is about giving realistic guarantees of security, a promise that you’re going to stick around for awhile and make sure that the Taliban don’t come back and chop their head off for collaborating. When the U.S. turned its focus to Iraq and poured men and resources there, they left 19,000 soldiers in Afghanistan. I mean, there are 40,000 cops in New York City! What kind of message does that send to the Afghani people?

The second thing is that I don’t think it’s possible to win a war without the cooperation of a stable and non-corrupt Afghan government. We’re not going to have success in Afghanistan unless we have a viable partner.

What should viewers take away from your film?

Why this film is important for the war in Afghanistan is that, regardless of political inclination, it shows what motivates soldiers in war. Understanding how they act in war is going to inform what we reasonably ask of them and what we should reasonably ask of them. That’s important whether you want to ramp up the war or whether you want to focus on a peace initiative. Whether you’re anti the war or pro the war, understanding how soldiers reasonably act in a combat situation is important.

The movie unnerved some people on the far left. They feel conflicted to feel empathy for soldiers when they’re against the war, but that’s missing the point. Information is power. Understanding how soldiers act in war is as important if we want to ramp up or scale down the war.

Should we still be in Afghanistan?

We went into Afghanistan for a reason, and that was because 3,000 people were killed in New York City. That’s quite a lot. That happened because the Taliban was a government that had no extradition treaties with the States. Before we went in there, they were asked to hand over Al Qaeda. They refused. Al Qaeda has runways, training bases, and telecommunications, and had formed their base in Afghanistan. They killed 3,000 people. We were in there for good reasons. Now we know that Al Qaeda and it affiliates have relocated into Pakistan, so the question is two-fold.

The first is for those who discuss civilian casualties, which are an important component of war. According to Human Rights Watch, about 17,000 civilians have been killed as the direct result of the war from 2001 to the present day. That’s a regrettable, terrible figure, but that’s nothing compared to the 400,000 who died as a direct result of the fighting by the Taliban and by warlords in the civil war. And that pales in comparison to the million-plus who died after the Soviets invaded Afghanistan. So in a weird way, Afghanistan is at its lowest level of civilian deaths since 1979. But that’s not a reason why U.S. forces should be in Afghanistan.

So the question goes back to why. If we are there for Al Qaeda, it’s reasonable to say we are acting as a magnet, but what do we do now? What happens if the Taliban takes back over? It’s reasonable to say that Al Qaeda gets a hand. It may be. The other possibility is that Pakistan is very unstable. Everyone says that’s where the problem is. The WikiLeaks show the depths of collusion between the ISI and the Taliban. The problem is that if we pull out, maybe the tables will turn the other way. … I can’t give you an answer, but the current prism through with which we’re looking at the war is a bit inadequate. We need to open up the conversation a bit more. The truth is, Pandora ’s Box has been opened, and the consequences of pulling out may be as grave as the consequences of staying.

After living through real war, do you feel any of the psychological damage endured by soldiers?

Yea, I think so. War is traumatic. Although I don’t go through nearly as much as a soldier, it is a traumatic experience. In a lesser way, everybody goes through traumatic experiences — if you have a good friend who dies, or you have a messy divorce, or you’re in a car crash. These are all traumas that can unnerve you. It takes time to get over them. War is obviously more extreme, due to the graphic nature. That can do something to your head, and sure, it takes a toll.

But I have a good amount of experience doing it, and if it’s going to happen, you have ways of dealing with it. You work out ways to work through that process. When I first got out of Afghanistan, I got depressed. My anger levels were rising and falling irrationally. I was hyper-vigilant, looking around all the time for stuff. When you come home, that is strange.

I was talking with a World War II veteran after a screening recently, and he said, “When we came back from the war, it took us months to get home on the ships, and we were with people who we’d been through the experience with. That was useful.” I hadn’t thought of that. Today, soldiers coming home is like cold shock compounded with trauma.

4•1•1:

Restrepo opens at Plaza de Oro Theatere (351 Hitchcock Wy.) in Santa Barbara this weekend. For more information, visit restrepothemovie.com. For more on Tim Hetherington, visit timhetherington.com.