Internet Pioneer’s Death Sparks Outrage

UCSB Researchers Chime In

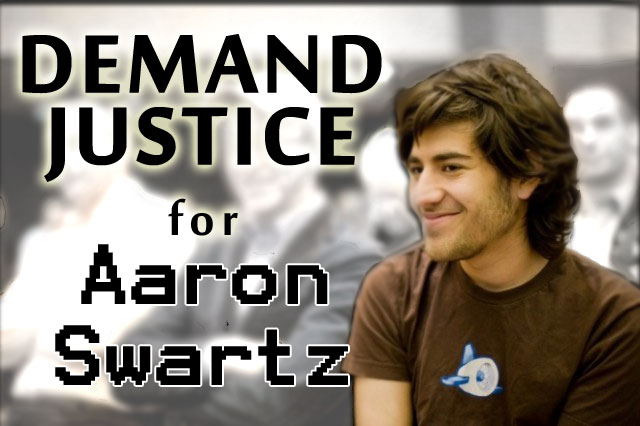

Widespread outrage and grief has erupted online after Aaron Swartz, a 26-year-old computer programmer and Internet freedom activist, committed suicide on January 11. Swartz was best known for his work on the RSS specification, a technology used on our very own independent.com website, and for cofounding reddit.com, the self-styled “front page of the Internet.”

As Swartz became increasingly involved in open data-access initiatives, he managed to attract the attention of the FBI — and eventually the U.S. Secret Service — when on July 19, 2011, he was charged with hacking JSTOR, a subscription-based digital library for academic journals, from a networking closet at MIT.

According to MSNBC’s contributor Chris Hayes, “At the time of his death Aaron was being prosecuted by the federal government and threatened with up to 35 years in prison and $1 million in fines for the crime of — and I’m not exaggerating here — downloading too many free articles from the online database of scholarly work JSTOR.”

JSTOR issued a statement after his arrest stating that it would not pursue civil litigation against Swartz. However, Assistant U.S. Attorney Stephen P. Heymann, under direction of U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz, decided to pursue criminal charges. According to Swartz’s attorney Marty Weinberg, they had “nearly negotiated a plea bargain in which Swartz would not serve any time.” However, it failed, since MIT would not sign off on it. Shortly after his death, MIT’s network was briefly taken offline and its website was defaced by “Anonymous” with a message in memory of Swartz.

Academic researchers expressed their outrage by making their publications available online for free, by posting links to their articles, and using the #PDFtribute hash-tag on Twitter. According to @PatrickSocha, an 18-year-old developer who created the website pdftribute.net to aggregate all the tweets and documents, there are at least 5,200 unique links and over 36,000 total tweets with the #PDFtribute hash-tag. Additionally, a group called The Archive Team recently launched an application called the JSTOR liberator and has since saved 2,795 documents.

UC Santa Barbara academics joined the chorus as well by tweeting their own research papers. Gianluca Stringhini, a computer security researcher and PhD candidate in the Computer Science Department at UCSB, and Adam Doupé, a third year PhD student in computer science, both published their research on their respective websites and tweeted out the links this week. They spoke to me about their participation in the #PDFtribute campaign and about the future of network neutrality.

I asked Gianluca Stringhini what inspired him to participate in the #PDFtribute action. “I followed the events surrounding Aaron Swartz pretty closely, and I was very sad to know about his death. He gave a great contribution to the web as we know it, and I thought that the #PDFtribute initiative was a great way of showing my support.” When asked about reforms to current laws, he said, “The copyright system needs to be heavily modified, to account for all the changes that our society and the way we share content has undergone over the last years.”

Adam Doupé, when asked what inspired him to participate, stated, “I fully support open access for scientific research. This is research that, for the most part, is funded by the government. That’s us. So why can’t the public freely access the knowledge that we’re paying for? Especially when that is the essence of science — increasing human knowledge.”

According to both Doupé and Stringhini, the computer science community does not publish very much research on JSTOR and thus isn’t highly impacted by its pay wall. Doupé did state, however, that “pay walls on research cause academic institutions to pay outrageous sums of money for access to content that academics need to do their job.” While most universities pay up and provide access to their own academics, the real impact is to “people outside academia, like yourself, who want to keep up-to-date on cutting-edge research. This makes it impossible for those people outside the system to contribute to science. Which is a shame!”

It is in large part thanks to Aaron Swartz’s activism that we continue to enjoy a free Internet in the United States today. Exactly one year ago, on January 18, the Internet flexed its collective muscle with a massively successful protest aimed at defeating two controversial piece of legislation. They were titled SOPA, the “Stop Online Piracy Act,” and PIPA, the “Preventing Real Online Threats to Economic Creativity and Theft of Intellectual Property Act.” If you are having a hard time understanding the nature of these bills, you aren’t alone. Millions of web users were shocked to hear about the proposals when socially conscious web developers replaced their websites for one day with layman’s-language versions of the proposed bills.

Over 100,000 websites participated and generated over 7 million signatures to a petition against the bills. Sue Gardner, the executive director of the Wikimedia Foundation, lauded the activists, saying, “You shut down the Congressional switchboards, and you melted their servers. Your voice was loud and strong.”

These bills, if approved, would have crippled and put under government purview the Domain Naming System (DNS), which is the virtual equivalent of the White Pages. It is a service that gets used every single time you attempt to access a website — the very same technique used by authoritarian regimes such as Iran and China to censor the Internet. According to the Open Net Initiative, at least 24 countries, containing 3.8 billion people and making up 54% of the global population, are now selectively filtering the Internet using similar tactics to what SOPA and PIPA were proposing.

Like Mohamed Bouazizi, the young man who set himself on fire, sparking the Tunisian revolution and arguably the entire Arab Spring movement, Aaron Swartz has become a lightning rod for the Internet community. Petitions have been launched, calls for legislative reform are getting stronger, and the Internet with its seemingly unlimited creativity is restless.

Increasing awareness for open Internet initiatives and continued solidarity for these concepts on behalf of the academic community are likely outcomes. However, as Adam Doupé said, “It’s the Internet; anything can happen!”