Cork Industry Barely Afloat

Environmental Ups and Downs with Move to Screw Caps

The great Whistler Tree of Portugal’s Alentejo region was already six years old when George Washington became president. Today, it is the oldest known cork tree. First harvested of its bark in 1820, the tree has been stripped from the waist down every nine years since, a standardized timeframe designed by the cork industry to protect the cherished European oaks from harm. At its year 2000 harvest, the stately relic produced approximately one ton of bark-enough cork to plug roughly 100,000 bottles-and the Whistler Tree is scheduled for its next stripping this summer.

But corks are going out of style fast, and by the time the Whistler Tree’s 2018 harvest date arrives, there might be no remaining demand for its crop. Even sooner than that, corks could become virtually obsolete; in a 2006 report by World Wildlife Fund, experts predicted that 95 percent of wine bottles will be capped with screw caps or synthetic stoppers by 2015.

Such an industry revolution will put an estimated 62,500 people out of work in Portugal alone, where 100,000 people participate to some degree in the cork industry. Portugal is the leader in cork production, generating 55 percent of the world’s supply each year and bearing about one third of the Mediterranean’s five million acres of cork oak forests. The trees, Quercus suber, are commercially grown nowhere else in the world.

The environmental impacts of shirking corks could be substantial, as well, and the historic cork forests rimming the Mediterranean Sea face an uncertain future as alternate means of bottle closure gain approval from winemakers and wine consumers worldwide. According to ngela Morgado, World Wildlife Fund’s director of fundraising in Lisbon, un-harvested trees will likely experience neglect and, although they are federally protected in several nations, they could even meet destruction.

World Wildlife Fund grew alarmed by the trend toward plastic and screw caps early this decade and, in 2005, launched its Cork Oak Landscapes Program, an international effort aimed at protecting the semi-wild forests throughout the Mediterranean. The trees, which strongly resemble California live oak, provide important habitat for lynx, eagles, and other birds and mammals. Perhaps more importantly, cork trees serve as a firm barrier against desertification. This phenomenon is already attacking Portugal from the south at a rate that could soon reach one kilometer per year, but if the native forests are protected and expanded, according to Morgado, the transition of forestland into sun-baked sand could be halted by 2020.

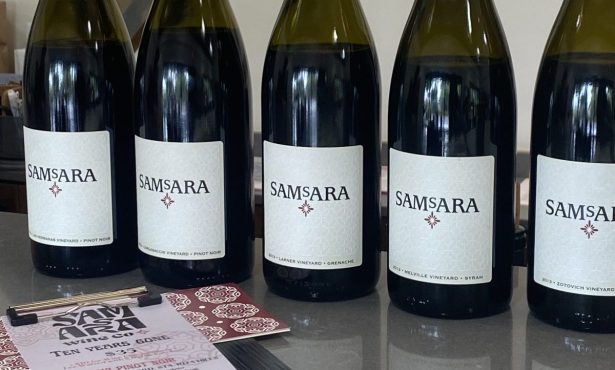

But the wine industry has its reasons for steering clear of tree bark bottle plugs. Firstly, synthetic stoppers are much cheaper than corks when purchased in bulk, and Priscilla Vazquez, wine buyer at Los Olivos Cafe & Wine Merchant, has seen the trend toward alternative closure methods primarily in the cheap wine category, which dominates the industry. Among high-end wines, said Vazquez, corks remain the favored closure tool, but even a few upscale wineries are exploring alternatives. In Paso Robles, winemakers Justin Perino and Steve Kroener began using a glass cork product last year called Vino-Seal for their two boutique labels, Nada Wines and Velvet Rope. The plugs are, in fact, more expensive than corks, but they are coated with rubber and create a perfect seal. The wines-reds and whites-“seem fresher” upon opening, said Perino.

The other important reason for the industry shift toward non-cork materials is cork taint. Cork taint is caused by TCA (that’s 2,4,6-trichloroanisole to the chemist), a bacterial growth that occurs both in the living bark of Quercus suber and in improperly sterilized corks. The musty condition, however, is rare; cork taint affects perhaps one percent of American wines, and cork-handling methods are improving, according to sources with the Cork Quality Council, a trade organization near Napa.

World Wildlife Fund is now working with the Forest Stewardship Council to design a program of stamping corks that have been harvested from well-tended forests, in which diseased trees are removed and healthy trees not over-harvested. Still in its planning stages, the certification system would likely feature an “FSC” stamp on the upper end of each cork, providing consumers with the chance to support one of the few fully sustainable-even beneficial-forest products there is.

“We believe that consumers want natural products that promote biodiversity and create jobs,” said Morgado.

But does the wine industry want the same? The Whistler Tree and thousands of other cork oaks are standing by, patiently waiting for the answer.