How to Fix the National Debt, with Pictures!

The federal government spends way too much. On this, those on the left and right should all agree. The disagreement, on spectacular display this October as the federal government shut down for over two weeks, is the degree to which our debt is an urgent problem and how it should be fixed. When we look closely, we see that we’re actually not as underwater as many think. And we could readily solve the long-term problems if we agree to cut back significantly on one major spending category: defense spending.

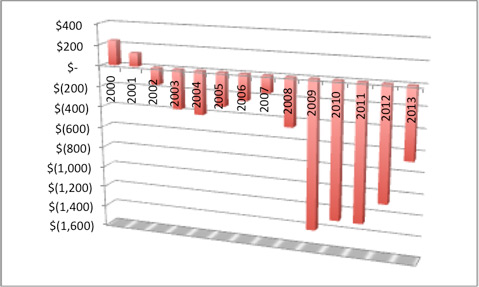

When it comes to the national debt, conservatives are right that we’re spending too much and that the debt is a problem. But I feel that they’re off the mark in their solutions and in the degree to which they worry about the national debt. The deficit is actually half what it was at its peak during the economic crisis of 2008 and 2009, which was the last budget set under President Bush. The deficit is projected to be about $670 billion for fiscal year 2013, down from a peak of $1.4 trillion in 2009 and $1.3 trillion in 2010 and 2011. This is real progress.

Figure 1. U.S. deficits in billions (source: Congressional Budget Office)

When measured as a percent of GDP (gross domestic product), the national budget deficit is also much lower, at 4 percent of GDP in 2013, as compared to almost 10 percent at its high in 2009. The Congressional Budget Office projects the deficit will fall to 2 percent of GDP by 2015.

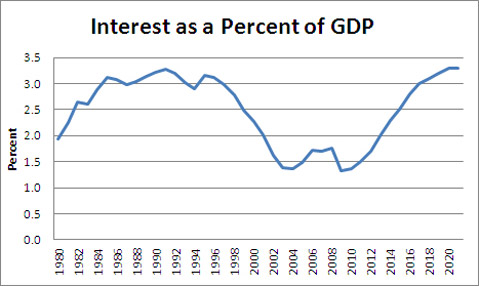

However, what really matters when it comes to our debt and deficits is the interest we pay on the debt. For example, if your mortgage rate is 3.5 percent instead of 8.5 percent, it has a huge impact on what you actually pay. The interest rate on our national debt is currently very low, and so the actual payments are very low.

As percent of GDP, the interest we pay on our national debt is less than half what it was in the 1990s under the first President Bush and Bill Clinton. The economy boomed in the 1990s even with the interest payments twice what they are now. There are, of course, a great many factors behind net economic performance in the world’s largest economy, but this recent demonstration of the economic impact of much higher debt payments than we have today is good evidence that our current debt burden is sustainable.

Figure 2. Federal interest payments as a percent of GDP (source: CBO)

So what gives? With the deficit on track to fall by 80 percent from its high in 2009, what’s all the fuss about?

What About the Long-Term?

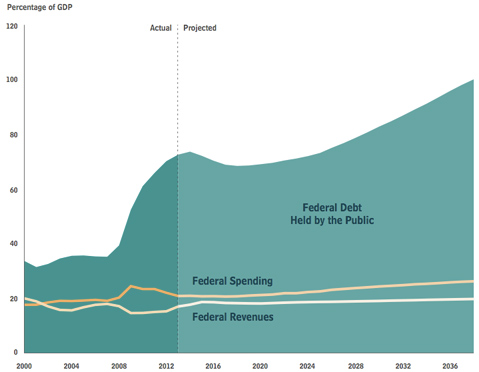

Well, in the long-term, there is still a problem. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO, a nonpartisan federal agency) projects that the trend starts to turn around again in 2018, and the deficit will, under current policies, return to 4 percent of GDP by 2023. But that’s 10 years from now. And we’ve already seen that 4 percent annual deficits don’t bring the economy crashing down. In fact, the U.S. looks pretty good compared to our peers in Europe or Asia in many ways, as the markets and continued strength of the dollar have shown. We could, and should, have a much stronger economy than we do, but it seems pretty clear that it is not our federal deficit that is the cause of our still-slow economic recovery.

(Many economists, including those at the International Monetary Fund, are now concluding that we have actually spent too little to get us back on track economically. The IMF, long a supporter of “austerity” measures — essentially national belt-tightening — has done a sharp about-face in light of the experience of European countries tackling their own recessions since 2008.)

CBO projects that by 2038 — 25 years from now — our federal debt will reach 100 percent of GDP, somewhere it hasn’t been since World War II. It also projects that interest rates will rise in coming years and that the interest burden from the debt will rise to 5 percent of GDP by 2038, up from about 1.5 percent today. That is a real problem, but it is five years from now before the interest burden even climbs above 2 percent — still well below the 3 percent it was during the mid-1990s. Five years is plenty of time to work on solutions that don’t require hostage-taking.

Figure 3. Federal debt as a percent of GDP (source: CBO)

What to Do About Long-Term Spending?

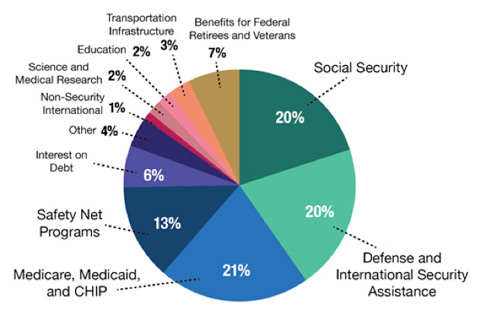

CBO provides yet another great chart showing how the federal government spends our money. The biggest expenditures are Medicare and Social Security, which are paid with payroll taxes rather than income taxes. The biggest expense by far that is paid with income taxes is defense spending, which amounts to at least 27 percent of the total budget when we include benefits for veterans and retirees. U.S. defense spending amounts to about 7 percent of GDP. But that’s just the headline figure for defense spending. When we add all the relevant expenditures, the total defense budget is about $1 trillion. This staggering number leaves a lot of room for belt-tightening.

Figure 4. Federal spending by sector (source: CBO)

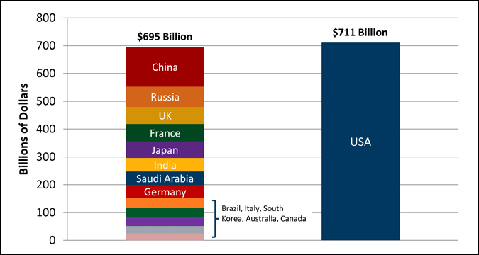

It’s helpful to compare U.S. defense spending to that of other nations. While we used to spend as much as the rest of the world combined, we’re at about 40 percent of total global defense spending now, while our economy constitutes only about 20 percent of global GDP. We spend about eight times our nearest competitor, China.

Figure 5. U.S. defense spending compared to other countries (source: Pete G. Peterson Foundation and Stockholm International Peace Research Institute)

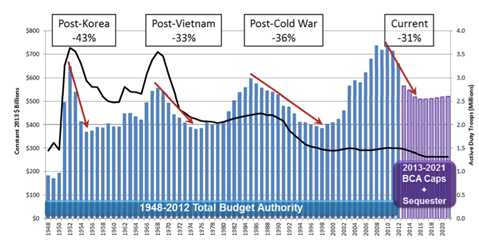

Isn’t the U.S. military budget already facing a lot of pressure? Well, sort of. The sequester kicked in for defense spending in 2013, and this will result in about $1 trillion less defense spending over the next 10 years. But this still results in astronomically high spending on defense — far beyond what is necessary for true defense. The following chart shows that spending will return to about 2004 levels after the sequester and stay there through 2020. Keep in mind that defense spending has actually risen each year under Obama, separate from the costs of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. This is itself a strange outcome considering that Obama campaigned on “ending the mindset that got us into the Iraq War” — aka militarism as a one-size-fits-all foreign policy.

Figure 6. U.S. defense spending history and projections (source: Center for Strategic and International Studies)

Cutting defense spending is not a new idea. There are many credible plans to do so. One good example was published in Foreign Policy magazine in 2011, by Douglas MacGregor, a retired army colonel and author of many books, including Warrior’s Rage. He called for cutting the budget essentially in half, resulting in $280 billion per year in savings.

If we were to cut the U.S. total defense budget in half by, say, 2020, the approximately $500 billion of annual savings (half of about $1 trillion each year) would go very far toward balancing our annual budgets and preventing our national debt from becoming the long-term threat that it may otherwise become. At the same time, we would be far less prone to “adventures” abroad. We can defend ourselves very well with a far smaller military budget, while at the same time avoiding the enmity of friends and enemies around the world who are rightfully resentful of our overly militaristic foreign policy.

I’m happy to find that my views are widely held when it comes to defense spending. People from both sides of the aisle agree that U.S. defense spending should be slashed far more than is being proposed by anyone in Congress. The American Conservative magazine has argued that our military spending is the greatest threat to our national security. So why isn’t Congress cutting the U.S. military budget? That’s a question for another day.