CAF’s Home Show, Revisited

Ten Los Angeles Artists Take On Santa Barbara’s Homes

It’s 8:30 on Sunday night, and I’m sitting on a blanket in the front yard of a modest home four blocks from the beach in Carpinteria. As a weathered and distressed silent surf movie unrolls on a small outdoor screen, I chat with the docent assigned to guide guests at this site. I’m at “home number nine,” the final stop on the Contemporary Arts Forum’s (CAF) fascinating new art exhibit/home tour, Home Show, Revisited. The film we are watching is “Dawn Surf Jellybowl,” the latest work by Los Angeles artist Jennifer West, and the casual domestic scene she has created deliberately echoes similar moments now decades in the past, times when surfers made their own films on Super 8 and toted the reels around from school auditoriums to backyards, drinking beer and snapping bottle caps at bedsheet screens.

The fact that this is 2011, not 1973, and that the 16mm negative has been, in the words of the artist, “sanded with surfboard shaping tools, Sex Wax melted on, squirted, dripped, splashed, sprayed and rubbed with donuts, zinc oxide, Cuervo, sunscreen, hydrogen peroxide, Tecate, sand, tar, and scraped with a shark’s tooth, with edits made by the surf and a seal while the film floated in the waves” only contributes to the ambiance, which succeeds in transporting the viewer to something like the free-spirited Southern California coast of the 1970s. As do many of the artworks in this must-see show, “Dawn Surf Jellybowl” lingers in the mind long after one leaves, spiraling outward through layers of history and community into a boundary-less zone where contemporary art and Santa Barbara home life merge and converge.

Where It’s At

For a long time — like 25,000 years — the value of art has been reflected in the places where it is found. Objects available at the neighborhood flea market are in one category, and those located in such prominent venues as New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the caves at Altamira and Lascaux, or the Uffizi in Florence are ordinarily quite another. Whether this is true because the location has historical significance or because the curatorial criteria for display there are known to be stringent, the result is the same: high status for the art.

For an American artist on the rise, the gold standard has for decades been inclusion in the Whitney Museum’s Biennial exhibition. On the international scene, there are the various pavilions of the Venice Biennale, Art Basel, Art Basel Miami Beach, and many more, all of them conveying status and granting essential validation to the works on display and to the artists who made them. As in real estate, so in art — the name of the game is “location, location, location.”

And location is exactly what makes CAF’s Home Show, Revisited, which is running weekends now through July 17, so interesting and unusual. Not only were the 10 artworks in this edition of the show created specifically for each of the nine homes and their residents; historically speaking, this show has also put Santa Barbara on the contemporary-art map. From its first incarnation in 1988 through the 1996 version, Home Show2, and now in Home Show number three (a k a Home Show, Revisited), the idea of site-specific art in Santa Barbara homes has captured the imagination of both big-time artists and international audiences. Co-curated by Michele O’Marah and Miki Garcia, Home Show, Revisited was written up in the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times before it opened, thus already receiving more national press than any other group show of contemporary artists in Santa Barbara this year.

Historically, the show has consistently attracted some of the world’s hottest artists, e.g., conceptual/installation superstars Joseph Kosuth and Ann Hamilton (1988), notorious provocateur Vito Acconci (1996), and video art pioneer Dan Graham (1996). In fact, several of the Los Angeles–based artists in the current version have shown recently in such high-profile spots as the Whitney Biennial and the Tate Modern in London.

Thus Home Show, Revisited revives a familiar paradox associated with domestic life in Santa Barbara: The most prestigious locations for art to be seen in this particular town may well be various people’s private homes. Let the New Yorkers and the Angelenos have their swanky museums, their openings populated with marquee names, and their blockbuster exhibitions funded by urban megabucks — in Santa Barbara, the best art comes to us. In tandem with its highly successful annual million-dollar home raffle, CAF has taken the dream of owning real estate in paradise and turned it into one of the most buzzed-about happenings in 21st-century art.

Hi, Honey, I’m Home

So what happens when contemporary artists invade private spaces? Obviously that depends on who the artist is, but, in this case, it also involves the people living there. The process for Home Show, Revisited began more than a year ago when informational meetings took place at CAF to answer questions from and gather information about the various residents who expressed interest in participating. For the homeowner/resident, the Home Show can be a significant commitment. You have to be willing to let strangers visit your home between 11 a.m. and 5 p.m. on Fridays and Saturdays, and noon - 5 p.m. on Sundays for two months. In addition, you have to be ready to collaborate with someone (i.e., an artist) who may be used to making all kinds of unusual demands.

For artist Bettina Hubby, the concept of home invasion formed the basis for her piece “Hubby Moves In.” Taking off from the idea of taking over, Hubby has created a work that turns the notion of privacy literally inside-out. She used the interior of Doug and Marian McKenzie’s home in Montecito as a photography studio for the weeks leading up to the exhibition, shooting self-portraits that depict her normal everyday activities as taking place in the private spaces of their home. Here’s Hubby sleeping with her dog, Bellmer, on the McKenzies’ guest bed, and there she is painting her toenails with the McKenzies’ motorcycle polish, or writing letters on their coffee table, or applying makeup in their bathroom. For the show, these images of the artist as houseguest were printed onto silk and hung as curtains outside the windows of the home. Visitors to the site experience the home invasion secondhand at the same time that they are denied access to the real current life inside the home. Out front, occupying the McKenzie’s guest parking space, is what, for Montecito at least, must constitute the exhibition’s most unsettling image — an empty portable storage unit covered with yet another giant photo on silk, this one of the interior of Hubby’s own storage unit in Silver Lake.

Needless to say, we’re a long way from the artist as adjunct to traditional interior decoration. The dynamic described by “Hubby Moves In” — in which the presence and practice of the artist sets in motion a series of questions about what’s public and what’s private and about how we preserve our secrets behind closed doors while presenting a carefully managed “front” to the street — recalls the origins of the Home Shows in the art of the 1970s and 1980s. And while the idea of artists using installations to initiate what was once called “an institutional critique of domestic space” remains an important part of the implicit mission of the Home Show series, there is now — and always has been — more to it than that. Even in 1988, when the idea of art as a rigorous form of intellectual investigation was near its peak of popularity, there were other questions being asked and other approaches being tried. One of the most important aspects of these Home Shows as a series is the way that they illuminate the shifting features and preoccupations of the art world over time.

Psychosis Focus

Two of the show’s most compelling projects manifest the drive to make connections not only with the home’s residents but also between the private obsessions of the artists and their hosts. At the home of artists James Van Arsdale and Kimberly Hahn in San Roque, Florian Morlat has erected a shrine to the greatest obscure Santa Barbara garage-rock band of all time, the Dovers. For those of you who are not vinyl junkies, the Dovers were a Beatles-worshipping group active in the mid 1960s who recorded a handful of 45 rpm singles on the Miramar label. These 7-inch records, which probably cost about 99 cents when they were new, are now worth thousands of dollars on eBay and at auction.

Morlat, a German who lives and works in L.A., has pursued the elusive Dovers singles for years, and he looked on the Home Show as an opportunity to represent both his admiration for their groovy sound and his near-obsession with their rare vinyl recordings. Originally intended for a site within the mountainous area affected by the Jesusita Fire, Morlat conceived a sculpture based on the shape of then-fashionable “Chelsea” boots, the slanted-heel footwear preferred by many musicians in that bygone heyday of real rock ’n’ roll.

Frustrated by the homeowner’s inability to share his vision for a large pair of upside-down boots on his property, Morlat had to switch locations midway through the project. “That’s when I realized that I had met James [Van Arsdale] before, at a record auction and that we shared this passion for the Dovers and for that period in music” Morlat said.

The resulting piece, a boot-shaped weather vane attached to the chimney, may represent a comedown in the scale that Morlat had in mind, but the fit of the piece to the home, which is filled with, among other things, Van Arsdale’s fabulous vintage record collection, could hardly be tighter. Rock on.

Over at David Court and Christi Westerhouse’s place on Sueño Road, artist Kirsten Stoltmann has installed what might be the show’s most memorable — and certainly most unsettling — piece. Each family was given the opportunity to set constraints at the outset of the project, listing the various things that they felt needed to be observed in order that the work not interfere overmuch with their daily routine. For Westerhouse and Court, the only constraint was that their young daughter, Francesca, be taken into consideration, as she has always ranged freely over the multiple indoor and outdoor spaces that make up this thoughtful and elegant custom home.

When Stoltmann met David, Christi, and Francesca, she said that she “knew immediately I had lucked out. I have a 7-year-old daughter myself, and she has taught me a lot, in particular about the aesthetics of collage, something I’ve been doing for a long time. When David and Christi told me to consider Francesca, I embraced the chance to collaborate with another little girl and to do something that would reflect that relationship.”

What Stoltmann created may not be everyone’s idea of art, but it certainly taps into some of the deepest issues and associations of the Home Shows. “I’ve always loved the middle-class suburban ideals of landscape and décor,” Stoltmann said. “They are what I grew up with, and I still like to work with them because underneath the external message that ‘everything is great in suburbia,’ I detect this trauma that’s just itching to get out.”

The piece, which was worked on boards, paper, and an area rug, consists of thousands of tiny stickers, plastic “bedazzle” jewels, broken toys, torn and burnt stuffed animals, and other detritus, all cooked up with a thick layer of glue to create the most horrific mess you’ve ever seen. Or at least that’s what it looks like at first viewing.

“Our friends are mostly art savvy, so they don’t freak out too much when they see it,” said Court, “but some of our neighbors who have come in look at it, and then at us, and it’s clear that they are kind of shocked.”

Upon close examination, the fireplace boards in particular appear to have been worked over with an almost unbearable intensity, with layer upon layer of stickers yielding a heavy, radically textured surface that generates a visceral response. Stoltmann gives credit for the discovery of this Mike Kelley–like aesthetic to her daughter, saying that “she taught me that it was okay to put things on top of other things. At first when I did collage, I had this idea that it was important to plan the pattern, and to be frugal with your materials, but when I saw her just plopping one sticker down right on top of another, something clicked.” Asked to say more about her methods, Stoltmann replied, “I didn’t want to make something that was just cool or hip looking. I felt like it was important to break through to this place where the piece had that quality that you see in the work of the autistic, when they are doing something over and over to calm themselves. I wanted it to look like the work of someone who might be possessed by the devil.” When I remarked that the work radiated an aura of intense focus, Stoltmann said, “Yes, psychosis focus!”

The Promise of More Life

Despite the persistence of such gestures toward the aesthetics of abjection and the mining of the domestic subconscious, Home Show, Revisited nevertheless incorporates many unexpected doses of sincerity and even utopianism. At the sophisticated, Michael Porter–designed State Street home of Candyce Eoff, Stephanie Taylor and Piero Golia have contributed lighthearted works asserting a playful, pleasure-seeking direction that seems well-calibrated to the atmosphere and purpose of the home.

Golia’s design for a small pool in the yard remains under construction as of this writing (Santa Barbara homeowners, can you relate?), but the accordion player from Taylor’s punning indoor installation was the hit of the VIP opening party that took place there two weeks ago.

Artist Evan Holloway’s miniature piece sits atop Elaine LeVasseur’s range in the kitchen of her home just off Alamar. Designed to be heated by the burners, and then sprayed with a mist of water so that it will release small billows of steam, the piece depicts classic modern sculpture in maquette. The steam refers to the access of consciousness supposedly generated by exposure to modern art in the museum or gallery, but the archness of the conceit is belied by the impact of the steam clouds, which consistently elicit oohs, aahs, and wows from those assembled.

At Nancy Gifford’s home on Sycamore Canyon, Jennifer Rochlin has added her painterly hanging ceramic sculptures to a setting already overflowing with great contemporary work. Gifford, an artist herself, has collected many sterling examples of the work of the best and the brightest of our community, and the Barry Berkus–designed modernist mansion in which they are displayed is itself a magnificent piece of architecture as sculpture. (Do yourself a favor, and contact Gifford for a tour of her collection when you visit this site. It’s one of our town’s most exciting hidden treasures.)

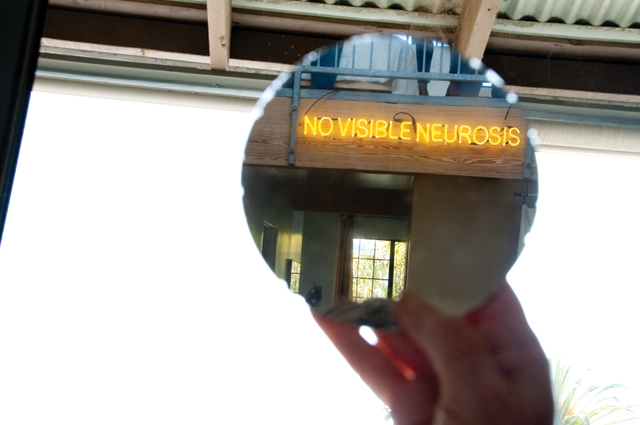

At Candice Assassi’s beachfront loft in Carpinteria, artist Kori Newkirk has made the implicit promise of so much Santa Barbara living explicit with a neon sign that reads “No Visible Neurosis.” The fact that it’s written backward and that to read it you need to look at it (and yourself) in an elegant modern hand mirror is all part of Newkirk’s clever commentary on what Assassi’s ocean-view home implies — clarity and grace, with life’s hang-ups and hurdles mostly receding in the rearview mirror.

One of the show’s youngest artists is also one of its most successful, and, once you’ve spoken with the amiable Ry Rocklen, it’s easy to see why. Chosen for the 2008 Whitney Biennial at the tender age of 29, Rocklen specializes in reworking salvaged materials into post-Duchampian readymades. His installation at the Eastside studio of mosaic artist Betsy Gallery fills her space with warmth and wonder and gives one pause to think of what changes may be forthcoming from a new generation of artists steeped in a collaborative and eco-conscious aesthetic.

I won’t spoil the experience by giving away too much — it’s a pleasingly interactive piece that requires visitors to shed their shoes — but I will quote Rocklen at his most expansive. “I like working with salvaged materials [in this instance, flea market paintings] because I love the richness and potency they bear due to the time and energy that’s been poured into them. Every square inch of this piece has been touched.”

The piece, which involves filling paintings with concrete so that they can be used as floor tiles, and then painting them with a checkerboard pattern to make them more regular and tile-like, is an homage to the mosaics on the walls and to their creator, the woman who lives there. “I liked Betsy’s work a lot,” said Rocklen, “so I made something that would allow people to stand on my work while they look at hers.”

In his modesty, perceptiveness, and ingenuity, Rocklen represents the spirit of Home Show, Revisited and of CAF’s Home Show series as it enters a new century. As it crosses and blurs the boundaries between public and private, leading art makers and their audience deeper into the lives of these generous participants, their friends, and their families, Home Show, Revisited renews one of the oldest promises of both art and home — the gift of more life.