Mission Impossible?

Against Long Odds, Harding School Revamps, Restructures, and Re-imagines its Future

As of this week, school’s out for summer in the Santa Barbara School Districts.

But while the sun-soaked months of June, July, and August will once again provide a much-needed respite from the grind of education for teachers and students alike, things won’t be quite so “livin’ easy” for the faculty and staff of Harding Elementary School on Santa Barbara’s Westside. Mired in flat-lined, far-from-proficient test results and facing federal sanctions for the fourth straight year from the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) program-President George W. Bush’s widely despised, test-score-dependent public education plan-the school has no choice but to drastically overhaul its approach to educating children. And fast.

For good or bad, by the time kids return to the classrooms at 1625 Robbins Street in late August, the school -led by polarizing principal Dr. Sally Kingston-will be both philosophically and structurally different. When the school bell rings, the incoming students will find themselves the subjects of a grand teaching adventure, with their classrooms as educational “labs,” more individual attention from their instructors, and an army of student-teachers from UCSB on hand to help. The credentialed staff teachers, meanwhile, will be facing their own challenges: Nearly half of them will be teaching a new grade and every one of them, whether they like it or not, will be facilitating an internationally developed paradigm shift in their approach to the curriculum as well as taking part in an innovative-though labor-intensive-weekly assessment of each student’s progress.

In short, as Kate Parker-president of the S.B. School Board, which unanimously supported the new Harding vision earlier this spring-put it recently, “It exciting, it’s dramatic, and it is going to be a radical change.”

School Yard SnapShot

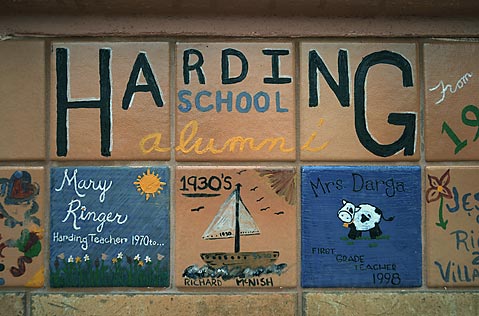

Founded in 1927, Harding is Santa Barbara’s oldest elementary school. But in its 82-year history, times may have never been harder than now for the nearly 580-student school that teaches preschool up through 6th grade. As hard hit by “white flight” as any school in the district, Harding has been struggling to maintain any shred of positive momentum in recent years. There’ve been leadership changes, the campus has been plagued by crime and vandalism, test scores have slipped well below both state and district averages, suspensions have been among the highest around, the PTA has disbanded, and the racism-loaded reality of being abandoned by families that live within walking distance of the school’s front doors have all contributed to the storm cloud that’s hanging over Harding’s culture.

By the numbers, as it stands today, Harding is nearly 95-percent Hispanic, more than 90-percent economically disadvantaged, and more than 70 percent of its pupils are considered English-as-second-language learners. Add to that an annual Academic Performance Index, based on state-standardized tests, that for years has been well below other California elementary schools with similar demographics, and you get one of Santa Barbara School District’s seven “Program Improvement” schools as mandated by NCLB. “The school has just been going nowhere for years,” said Parker. “And that is simply not fair for the students. Something has to give.”

When a school enters its fourth year of NCLB sanctions, as Harding is about to do, one of four things must happen: (1) It must close and reopen as a charter school; (2) the district must replace most, if not all, of its staff, including the principal; (3) an outside entity must be contracted to run the show; or (4) the school must undergo a drastic redesign. On April 28, the Santa Barbara School Board approved the last, a two-pronged approach that partners Harding with UCSB’s Gevirtz Graduate School of Education while also implementing an International Baccalaureate (IB) Primary Years program for all the school’s students, which, if succcessful, would make Harding the South Coast’s first IB World School. (It should be noted, however, that Dos Pueblos High School has operated a successful IB school-within-a-school program since 1997.)

It is, according to Principal Kingston, “nothing short of a whole-school reform.” And, according to UCSB’s Gevirtz School Dean Jane Conoley, who is involved intimately in the revamp, it’s rather revolutionary for a suffering school. Conoley explained, “This is something you would typically see started in a community of rich white kids.”

“Going IB,” as they say, is an ambitious, genre-bending approach to education. Developed in Switzerland in the late 1960s, the program-which traditionally has been used for high school kids and only in recent years was adapted for younger students-aims to develop globally minded citizens via an inquiry-based classroom. In general, it’s not about teaching specific lessons in the traditional sense, but instead is focused on getting students interested in a subject and prompting them to ask questions so they discover the lessons on their own. Explained Kingston, “It is a lot more asking than telling.”

Specifically, the curriculum works to transcend the borders of such traditional subjects as math, science, social studies, and reading by making six “themes” of learning paramount to all students, no matter what subject or grade they are in: (1) who we are; (2) where we are in time and place; (3) how we express ourselves; (4) how the world works; (5) how we organize ourselves; and (6) how we share the planet. Furthermore, the program requires extensive and deliberate teacher cooperation, both horizontally-so that a 5th grader’s science class will have more in common with her history class each day-and vertically-so that an incoming 4th grader will pick up where he left off in 3rd grade. The program is designed to prevent needless overlap and give students more continuity throughout their days and years. A final calling card of the IB program is a mandatory foreign language component for all students, regardless of achievement levels.

Not So Crazy

Harding School started looking at the IB option more than a year ago-a feasibility study on the transition was approved by the School Board in August 2008-and sent a leadership team down to Pasadena Unified School District’s Willard Elementary. With a racial and socioeconomic student body makeup similar to Harding, Willard (which has been an IB school since 2001), has achieved both statistical and anecdotal success. Last year, Willard even met the lofty standards of NCLB. Curious to see this first-hand, Kingston and a handful of teachers went to investigate and determine whether an IB approach would be a good match for Harding. “You know what?” recalled Jennifer Lindsay, an 11-year veteran of Harding. “It didn’t look too dissimilar from what we have been doing the last few years.”

Turns out that Harding School has, in fact, been somewhat IB-esque since 2005, when Kingston first arrived as principal. With a jam-packed and hopscotching resume that’s surprisingly prolific for a 43-year-old-including kindergarten and 1st-grade teacher at Monte Vista in Santa Ana (1988-91), 2nd-grade teacher at Peabody School (1991-94), assistant principal at La Colina Junior High (1997-98), principal of Franklin Elementary (1998-99), principal at Roosevelt Elementary (1999-2002), assistant superintendent for the Santa Barbara County Education Office (2002-03), director of UCSB’s Center for Effective Schools (2003-04), and consultant for a Colorado education firm (2004-05) -Kingston, also a well-published educational author, is not short on opinions about how to run a school.

To that end, for the past two summers, she has been facilitating informal “summer institutes” for Harding teachers that have focused specifically on integrating curriculum and continuation. And, falling in step with the globally conscious goals of IB, Harding recently has ramped up its recycling efforts, started an organic and zero-waste cafeteria, buffed out the technology department, and secured funding for a large-scale garden to be planted later this summer. As a result, Lindsay sees the hopeful IB transition as more of an evolution to something that Harding already has started rather than a world-changing overhaul. “It really just gives us the structure to pull everything together,” she explained.

That doesn’t mean it will be easy, as even Kingston admits the switch to IB will be a “slow and challenging process.” While 10 teachers already took IB training courses this past March during a spring-break trip to Cincinnati, there’s still far more work to be done. Despite plans for IB-specific in-service days this fall and heaps of on-the-fly adjustments to curriculum once the school year gets started, the reality is that no one knows what things will really look like until the kids come back and classes start. Luckily, that is where the second part of the restructuring plan comes in.

While Harding School is no stranger to UCSB students, thanks to an ongoing relationship with the Gevirtz School, the nature of that partnership is about to change in a big way. “We are moving beyond just sending help and we are going to start doing shared decision-making,” said Gevirtz’s Dean Conoley. Though the redoubled partnership’s specifics aren’t yet clear-the design team has its first meeting on June 10-Conoley envisions a mixture of professors, student-teachers (equal, perhaps, to the number of full-time credentialed teachers), and undergrad student tutors helping out at Harding, from preschool to 6th grade. The result will be what they’re calling a “lab school,” and the idea, said Conoley, is to implement research-based intervention programs (a NCLB mandate), assess student response on a practically daily basis, remain flexible, and keep striving for improvement regardless of standardized test results.

“In the long run, it isn’t important whether or not they pass one state test,” said Conoley. “Keeping kids engaged and constantly learning is what matters. They will be the barometer of our success.” In that regard, she believes the IB format is the perfect complement. “The earlier you start [with a student], the better, and the more consistent you are, the better,” said Conoley. “And an IB program does just that.”

International is Not For Everybody

To say that everyone at Harding is supportive of the transition or of Kingston’s overall vision would be a gross inaccuracy. When the changes were approved, at least five teachers-or about 20 percent of the faculty-quickly asked to be transferred, including one whom a school insider recently described as “among the best in the school.” And who could blame them, really?

Under the new format, teachers who’ve taught 3rd grade their entire career might find themselves teaching kindergartners next year, and they’ll probably get stuck mentoring a student-teacher or two as well as learning a new, labor-intensive curriculum-all for the same salary. Furthermore, while the school district and the Santa Barbara Teachers Association have worked happily to facilitate these changes, there still is plenty of off-the-record grumbling about whether or not IB and a “lab school” are in the best interest of Harding’s already hurting students.

Others, it seems, simply are uncomfortable with Kingston’s take-charge attitude and some question her qualifications, especially with so many jobs in so little time. “She was fine if you don’t mind a boss who doesn’t say hello,” said one former colleague. “She has zero social skills and doesn’t want to be bothered with the messiness of kids.”

Although she’s quick to admit that her Harding job will be her longest tenure ever, Kingston is unapologetic about the feather-ruffling. Describing herself as “fair but tough,” the principal says people are leaving for one of three reasons: “They don’t want to go through the IB training, they don’t like their new grade assignment, or they just don’t like me.” No matter the reason, the bottom line for Kingston is having everyone be on the same page. “For this to work,” she explained, “we have to have school-wide balance and full teacher commitment.”

Another fear factor is that signs of progress shown during the past two years- namely, rising test scores for Harding’s youngest grades (which are not reflected in overall state rankings) and increased enrollment for next year’s kindergarten class-may be lost if things are tweaked too much or too often at the school in the name of NCLB. But these fears are unwarranted, said the district’s Associate Superintendent Robin Sawaske. One of the authors of Harding’s restructuring plan, Sawaske described the changes as being “more of a continuation than an actual momentum-fighter.” After doing monthly walk-throughs at Harding and meeting with faculty and staff, Sawaske said the IB and lab school options would “absolutely” be viable even without the federal sanctions.

While Kingston promises she “wouldn’t do anything that wasn’t moving in the direction of better test scores,” the principal also was very upfront with the school district from the beginning, early on telling district Superintendent Brian Sarvis, “If you want me to just raise the test scores, then we might have a problem, as that will bump up against my core beliefs.” She further explained, “I believe we have a moral obligation to help every kid possible. : It is not just about tests. I mean, what happened to the learning part of school?”

A Hard Truth

Harding’s battle is decidedly uphill, no matter how ambitious or remedial a restructuring plan the school puts in place. With a multibillion-dollar state deficit figuring to wreak havoc on public education funding for years to come and NCLB performance standards all but impossible to achieve-especially for English-as-second-language learners-Sawaske recently opined, “It is almost literally impossible for [Program Improvement] schools to get out of it at this point.”

The path ahead for Harding looks to be full of potentially perilous pitfalls that are beyond its immediate control. If that’s the case, then perhaps the most appropriate goal for the school should be to do nothing more than ditch the bad reputation that has followed it in recent years and once again become a vibrant neighborhood school. Only time will tell whether IB and classroom labs will get them there, but, at least for now, they have a leader who, whether you agree with her or not, has a distinct vision of what the finish line looks like.

“I am proud to see how far we have come as a school community and how much we have overcome in terms of rebuilding a school that felt torn apart,” said Kingston. “My greatest joy will be for Santa Barbara to have at least one underperforming school rise to a high level of performance. I believe we can take the lead on that.”