Veteran’s Day: My Father’s Rosebud

Author Learns of a Hidden War Story As His Dad Approaches Death

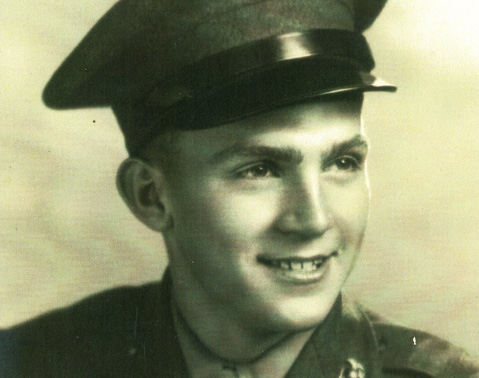

My father was a veteran. He was in the United States Marine Corp.

We knew this growing up, but my father, Frank Dahlstedt, rarely talked about his service until the week before he died. I was driving him from Bakersfield to Santa Barbara in search of medical treatment and we had some time alone to talk.

He told me that he was Sergeant of the Guard at the POW camp in Guam. They were conducting War Crimes trials for the Japanese officers, primarily for their offenses against the people of Guam during the Japanese occupation.

One day, he was relaxing in his quarters when he was told to report to his duty station. When he arrived, he noticed the officers, more than he had ever seen at the guard house.

Then he noticed the blood. He’d seen blood before but not this much. It soon became apparent that one of the prisons had committed suicide.

At first, he did not understand why all of the officers were there. Then it hit him: The blood was coming from the special cell, the one that held the star witness for the prosecution of the Japanese officers. This was a Japanese officer who had turned on his compatriots and testified against them.

Now that he had killed himself, the prosecutors lost their key witness. They were angry. Heads were going to roll. My father was confined to his quarters and, along with the Sergeant of the guardhouse, was to told to expect a court-martial. He was just 18 years old.

Four short years earlier, my father and his parents moved away from the family farm in Nebraska, which they had lost in the Depression. He’d spent his boyhood helping his father with the crops and the cattle in the home his grandmother built. From there, he landed in Pasadena and graduated from John Muir High School.

At the time, World War II was raging, and every boy over 15 was constantly asked why they weren’t fighting. Like many others, my father joined up at 17-and-a-half years old, and was quickly sent off to war. Fortunately for him, the war was essentially over when he finished boot camp, so he was not exposed to the many horrors that others endured.

Suddenly he found himself confined to his room and in deep trouble. Although he had time to write his parents, he did not know what to say. His older brothers were both serving proudly and his parents were proud of him. His mother had a photo on her mantel of her three boys in dress uniforms taken just before they shipped out.

Now he was facing dismissal, disgrace, and what else? He had lots of time to think about his life and his future.

After three days, it ended as quickly as it began. He was told to report to duty, as if nothing had happened. He learned later that a requisition form had turned up. A second lieutenant had, at the request of the prosecution, approved the prisoners possession of a razor in order “to look good for trial.”

A week after he told me this story that he’d hidden for so long. my father was on his death bed. As we sat at his bed waiting for the end, he went in and out of consciousness. We watched the Angels on TV, and he would sometimes see bugs on the wall that turned out to be reflections from the windows.

He’d been a milkman for 30 years in the San Gabriel Valley, so he also asked for milk and would reach for it, even though it wasn’t there and he couldn’t swallow even if it was.

And, although we at first believed he just wanted to shave, he would at times point to the shelf in his room and say to me, “Robert, I see it. I see the razor.”

Robert Dahlstedt worked as a public defender for 35 years in Tulare, Ventura, Riverside, and Santa Barbara counties. He’s lived in Santa Barbara since 1988. His father died in 2009.