The Anatomy of Cyclic Steaming

What’s the Hot and Bother over Next Election’s Biggest Issue?

Call it “cyclic steam injection,” as the oil industry does. Call it “huff and puff,” as the environmentalists do. Call it whatever you want, as long as you preface it with “controversial” since the extraction method is the front and center issue of this November’s election.

Spearheaded by an activist group dubbed the Water Guardians and bolstered by signatures from more than 16,000 county residents, an initiative on the next ballot aims to ban all new oil projects involving hydraulic fracturing, acidizing, and cyclic steaming. The Water Guardians has so far focused most of its outreach on the initiative — now known as Measure P, for “protection,” the group says — on hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, a polarizing practice that other jurisdictions across the state have recently outlawed. But because the county’s new fracking rules have scared off applicants, cyclic-steaming companies could suffer the biggest blow if the measure passes.

Although the process has had a foothold in California’s oil fields since the 1960s and in Santa Barbara County’s since the 1990s, H₂O-dependent cyclic steaming hadn’t until recently attracted as much of the public’s attention as its ballot companions have. The spotlight came last November, when the supervisors approved Santa Maria Energy’s 136 cyclic-steam-injection wells.

Since then, other regional oil companies have expressed increased interest in the technique. Pacific Coast Energy Company, whose Orcutt Oil Field sits next to Santa Maria Energy’s operations, applied last fall to add 96 wells to its existing 96. In March, PetroRock LLC got the green light for 56 new wells. This month, ERG Operating Company submitted its application for 233 cyclic steaming wells, an application that could soon be joined by Aera Energy’s whispers of 200-300 cyclic steaming wells. And Santa Maria Energy, in its now-scuttled bid to merge with a New York investment firm earlier this year, was found to have enough property to drill another 7,000. Overall, the majority of the 903 wells on the Planning Department’s radar are going the steam-injection route.

But the industry’s expansion plans could be mere pipe dreams if the public buys environmentalists’ arguments over the companies’ assurances. Where Santa Maria Energy and Pacific Coast Energy Company cite strict state rules, advanced monitoring systems, and responsible water usage — plus high-paying jobs and much-needed tax revenues — area activists worry about endangered oil-field workers, environmental catastrophe, and an ongoing investment in emissions-generating fossil fuels extracted with a water-reliant method in the face of climate change.

Since Santa Maria Energy came onto the scene, the company has been quick to differentiate itself from fracking, saying repeatedly that that process differs greatly from its own and, further, would be antagonistic to cyclic-steaming operations in general. “We already have a frack-free Santa Barbara County,” said Santa Maria Energy’s public and government affairs manager Bob Poole, who speculated that banning fracking isn’t the measure’s goal. “It’s to shut down oil production in Santa Barbara County onshore. Make no mistake about that.”

From Huff to Puff

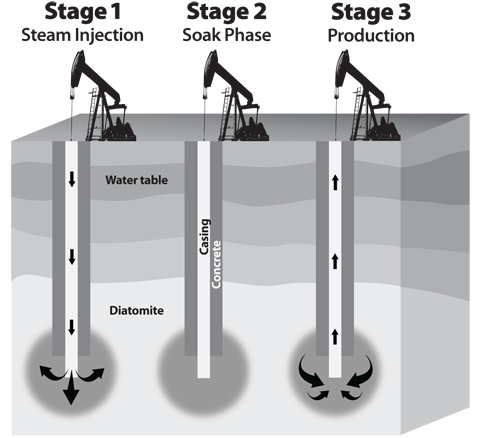

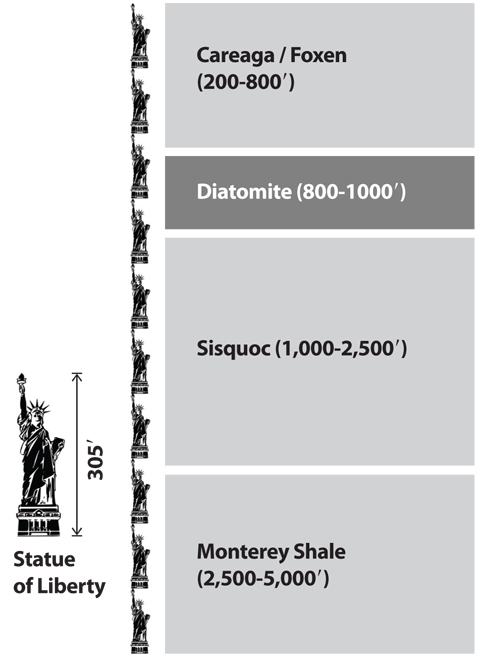

Directly underneath the Careaga formation and well above the Sisquoc formation and Monterey shale, about 1,000 feet below the surface, lies diatomaceous earth, a porous rock popular in cat litter and pool filters. It also holds anywhere from 12 million to 80 billion barrels of very viscous oil statewide, with billions in Santa Barbara County. And because the rock prefers water to oil, the best way to get the oil out is to trade it for H₂O. The companies introduced water into steam, heating it up to 400-550 degrees, and inject it — the “huff” stage — into the ground at a pressure of approximately 1,200 pounds per square inch.

If the days-long injection process is considered the first phase of the titular cycle, the soaking is step two. Over time, usually a matter of days, the heat works to thin the oil and release it from the pores, readying it to be pumped to the surface for the “puff,” the third and final stage that can go on for weeks.

Wells can produce for about 30 years, but the oil-recovery factor with cyclic steaming resembles a bell curve, said Kevin Drude, the deputy director of the county’s Energy Division. In its first year of life, Drude said, a successful well would yield about 50 percent oil, a figure that could drop to 5 percent over time. Cyclic steaming’s separation from fracking and acidizing is twofold, Drude said. First, unlike those methods, it doesn’t break or dissolve the rock. Second, no chemicals are injected into the ground.

But the use of the water itself — and the energy it takes to heat it — is where the environmental concerns come in. The process is much more “carbon intensive” than traditional drilling, which can emit a quarter of the emissions of a cyclic-steaming operation for the same number of wells. While pipelines for oil and water — as is the case with Santa Maria Energy’s project — can help reduce transportation-related emissions, the gas-powered steam generators required for the process can pump thousands of metric tons of carbon dioxide into the air. (Santa Maria Energy’s 136 wells will likely emit 88,000 metric tons annually, equivalent to the emissions from more than 18,000 cars.)

Although none of the projects coming before the county have proposed to use groundwater for their operations — with the exception of Pacific Coast Energy Company, whose new 96 wells would require more than 1.3 million gallons from the company’s private water wells during construction — their use of non-potable recycled wastewater and the water brought up with the oil in conventional drilling has environmentalists worried.

Santa Maria Energy’s project, for example, will receive about 300,000 gallons a day of the 2.4 million gallons of wastewater that the nearby sanitation district handles, most of which is used to irrigate crops and keep golf courses green. Next door, Pacific Coast Energy Company uses 300,000 gallons a day for its 96 wells, acquiring that water from the 3.5 million gallons it recovers from its traditional drilling activities.

Many question whether the county should wed its resources, especially during extreme drought, to the oil industry, and question further whether there is enough of that wastewater and recovered water for hundreds of additional wells. Kevin Drude said the county has plenty of that type of water to go around: “There’s absolutely an abundance of it.”

Leaks, Seeps, and Safety Issues?

With water also come worries that the wells could fail and leak into the water table, which sits about 200 feet below the surface but above the diatomite. Each well is lined by a casing and then surrounded by concrete, safeguards meant to minimize the oil’s escape, Drude said, adding that he has never heard a report of a groundwater issue in his years in the department.

But that doesn’t mean it hasn’t happened elsewhere, said Assemblymember Das Williams, who recently took the reins in speaking on behalf of the Water Guardians. Williams cited a study showing that well casings can fail sometimes, noting an incident in Alberta, Canada, where an aquifer and lake suffered contamination because of such a failure.

Pointed to more than any other event is a 2011 tragedy in Kern County in which a field worker died after he ran toward a steam eruption and the ground gave way. That type of eruption, known as a “surface expression,” is man-made, Drude explained, distinguishing between those and seeps, which occur naturally but can be exacerbated by cyclic steaming.

For the past year or so, seeps have dogged Pacific Coast Energy Company, which had to install 94 15-foot-long emergency seep cans — the company collects the oil and adds it to its yield — for its 96 wells. Jim Bray, the public and government affairs manager for Pacific Coast Energy Company, chalked the seeps up to basic geology. “Natural seeps have been occurring at Orcutt Hill for eons,” he said. “That’s why Mr. Orcutt came here.”

The company has since worked with the state to decrease its seeps — and must come up with a plan to address seeps for its new project — by playing around with the temperature and pressure, Drude said. But environmental advocates allege it is that constant changing of temperature and pressure — which Drude likened to a balloon losing its helium — characteristic of cyclic steaming that can lead to problems, including shifts in the ground that can lead to leaks and surface expressions.

The wells are designed to withstand such high pressures and temperatures, Drude explained, while cautioning that, like with everything else, adverse effects and accidents can always happen. “Nothing’s perfect,” he said. “Nothing’s 100 percent.”

Barrels and Cents

In 2011, before Santa Maria Energy’s operations — projected to produce 3,300 barrels per day — were approved, Santa Barbara County’s cyclic-steaming operations accounted for about 1,700 barrels per day of the state’s 75,000 daily diatomite-sourced barrels, which was only a fraction of the 505,000 total barrels of oil sourced from the Golden State on a daily basis.

Cyclic steaming has occurred in Santa Barbara County for years — Pacific Coast Energy Company’s original 96 wells were approved in 2006 — but Santa Maria Energy’s proposal was the largest such project to come before his department in years, Drude said. The rates across California and the county are only expected to increase, but the hundreds of wells proposed by area companies will hang in the balance of the ballot measure.

Opponents of the ban contend that nixing future projects would also mean nixing future high-paying jobs in a poverty-rich North County (Santa Maria Energy employs 80 full-time staff and contractors; Pacific Coast Energy, about 250) and additional property-tax revenue for the county, which already scores more than $16 million from the industry. And threatening future projects, as this ban does, likewise threatens existing projects, Poole and Bray said, as their companies’ present plans depend on the future. But Linda Krop, chief counsel for the Environmental Defense Center, which is now co-representing the Water Guardians, said that argument doesn’t pass her sniff test. “If they’re making money off their existing operations, they’re going to continue pursuing those existing operations,” she said.

Leadership Position?

Where Poole said the industry is “being bludgeoned by misinformation,” the Water Guardians and its supporters say now is the time to act. Senate Bill 4, which aims to regulate fracking and acidizing (but not cyclic steaming) across the state, is “better than nothing,” Williams said, but not enough. Santa Barbara, “the birthplace of environmentalism,” Williams continued, could play a leadership role on this issue. “Our community is more important than increased drilling with dangerous techniques such as fracking, acidizing, and cyclic steam injection,” he said.

Michael Chiacos of the Community Environmental Council, which has also come out in favor of the measure, acknowledged the argument used by industry officials — that oil is here to stay, and if it’s going to be produced, why not produce where the rules are strict? — but said the ban could point the county in a new direction.

“Most of us drive, and it’s very easy to say, ‘No oil drilling in our backyard,’ but that oil has to come from somewhere,” Chiacos said. “We realize it’s really easy to say no to oil drilling; what’s harder is for people to say yes to alternatives to oil.”