La Dolce Vita Is Not for the Timid

Sweet, Sensuous, Salvo-Filled

In case you were wondering, the title is clearly ironic. But don’t worry; lots of people, including many who’ve seen La Dolce Vita, assume it’s a kind of advertisement for the swinging ’60s.

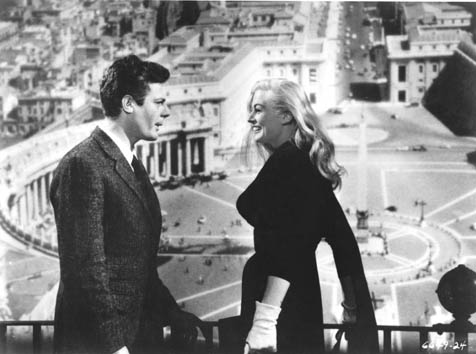

There are reasons. It was already a winking reference back in, as they say, the day. In “Motorpsycho Nightmare,” Bob Dylan describes a sultry farm girl “whose name was Rita / Looking like she just stepped out of La Dolce Vita.” Donovan (stealing) in “The Trip” evokes another damsel looking “like she stepped out of a Fellini film / Sitting in a white straw chair.” It implied everything exotic in the emerging hipster culture, like a signpost to an orgy. Even though Fellini’s working title for La Dolce Vita, which screens this Wednesday, August 29, at Campbell Hall, was Babylon 2000. Even though a cursory viewing will convince you this vita Marcello Mastroianni wanders through is maybe sexy but decidedly not so sweet.

Granted, some critics think it wasn’t grim enough. The owlish David Thomson claims the film reflects a mere “sluggish dismay at corruption” when compared to the more thoroughly “metaphysical” revulsion in Antonioni films like L’Avventura or (my favorite) La Notte. Both made, by the way, within a year of La Dolce Vita. Maybe he’s right, though. The Antonioni films, though coldly beautiful, echo with the futility of love and the unfriendliness of the universe, while Fellini likes to show a lot of cleavage.

What’s missing from Thomson, though, is the sheer number of themes Fellini packs into his funhouse: innocence, faith, the poverty of theory, and detachment, just to name a few. La Dolce Vita doesn’t only tackle the mores of post-war Italy. It’s sensuous fun and then it fires off some stiff salvos.

Consider the opening scene. A giant statue of Christ dangling from a helicopter first crosses over a Roman ruin and then a sea of modern apartment houses and high-rises. Spotted by a bevy of bikini-clad women (bikinis were new then) sunbathing on a roof, one of them yells, “Look, it’s Jesus. Where is he going?” Then we see our hero, Marcello, bemused in the ‘copter, first explaining the statue is going to the Pope who lives nearby, then asking the woman for her phone number. But the helicopter’s too loud. The levitation miracle crosses Roman epochs and ends in world-weary shrugs.

The nonlinear storyline of La Dolce Vita is sometimes described as narrative Cubism, self-consciously inspired by Picasso, whom Fellini had recently met. So much rationalization has been made for the random-ish plot structure, it’s pointless to reiterate the critical debates centering around levels of Hell or Deadly Sins, et cetera. But, I say the most pleasing aspect of the film is the relationship of canny bits to a luminous whole: the logic of dreams that move forward by poetic streams of association, the rhyme of images, ending, famously, with a goggly-eyed monster that could be Christ, or nature, or just the object we are watching staring back at us.

In fact, the very act of seeing is how I see the film. There are voyeurs everywhere beginning with us, naturally, and then our hero, Marcello. Remember, the first word in the film (“Look!”) is also one of the last intelligible words, too (“it looks at you”). The film is chock full of eye-images: headlights, raking spotlights, sunglasses, and, of course, photographers. (The word “paparazzi” was invented here.) Fellini’s film wanders history, nature, and a studio-recreated version of hipster Rome to visually cross-examine la vita, finding it beautiful and empty: The sweetness of life is always escaping us, because we can see it, but can never possess it long. It’s not really existentialism; it’s more like Boccaccio or Keats.

But maybe Thomson’s right. It’s not grown-up brooding and high modernist enough with architectural surfaces reflecting a geometry of despair. It’s a slightly more lively version of desperation, a little flip, a glib version of mass culture terror. And, it’s got super-cool Marcello, Anita Ekberg, the young Nico, and the dazzling Anouk Aimee, sadly radiant, of course, and sometimes sitting in a white straw chair.

4•1•1

Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita screens at UCSB’s Campbell Hall on Wednesday, August 29, at 7:30 p.m. See artsandlectures.ucsb.edu or call 893-3535.