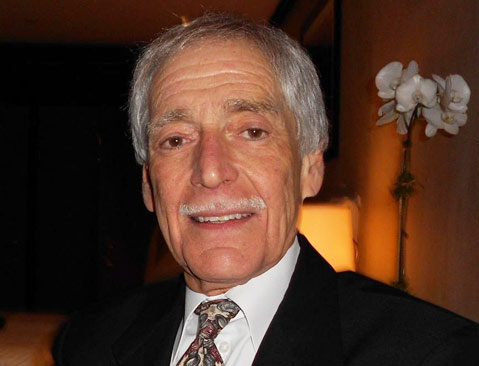

Dan Shackman died on March 20, prematurely losing the enjoyment of a life in retirement we had both looked forward to. He was my anchor in life — the man I loved — with whom I had shared the past 41 years. He was also, more broadly, a valued member of the Santa Barbara medical community.

Dan was born, raised, and educated in New York, and after serving as base psychiatrist at Fairchild Air Force Base in Spokane from 1970-1972, he relocated to Southern California. Practicing psychiatry in Santa Barbara for the past 28 years, after more than a decade in Los Angeles, where he directed psychiatric admissions at the Brentwood Veterans Administration hospital, Dan was second to none in his love of our city. He called The Santa Barbara Independent his “paper of record” and travel away from Santa Barbara “the forced march.”

He was a man of remarkable intellect and a mind-boggling range of knowledge — from popular cultural trivia to opera and classical Greek literature. He was also the most superb medical clinician I’d ever known, a conceptual thinker who was always “outside the box” in analyzing medical issues, connecting dots often missed by other physicians. A psychiatrist by profession, he was, not surprisingly, also an exceptionally good listener.

From childhood on, Dan was destined to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a physician, but his great passion in life was music. Beginning as a teenager, he was always in an amateur band, whether as the drummer, guitarist, or lead singer — usually also the manager of the group. In high school, his band included Al Kooper, who later became a member of The Blues Project. As an undergraduate, he was a member of Columbia University’s a cappella Kingsmen, and in subsequent years, he wrote, and performed in, the annual send-up musical revues at its medical school. During his years in Santa Barbara, it was performing with informal neighborhood jam groups that made him happy. While old rock was his favorite genre, he had an encyclopedic knowledge of all types of music. Medicine and music held equal places in his heart: He would lightheartedly suggest he was just as impressed by Al Kooper’s career as a musician as he was the Nobel prize won by Harold Varmus, one of his medical school classmates.

Dan’s whimsical way of experiencing much in life was a characteristic element of his sense of humor. When asked why he chose to attend medical school at Columbia when he had the option of several of the Ivies, Dan responded that he preferred the Hudson River to either the East River or the Charles. Of fulfilling his military service obligation under the “Berry Plan,” he said the air force won because they had the nicest officers’ uniforms. Whether he was serious about either quip, I never really knew. But I do know that he accurately summarized a unique virtue of my career as a tenured professor at UCSB: “Where else,” he asked, “does one have no boss and your ‘customer’ is always wrong?”

More significantly, perhaps, Dan was a psychiatrist of the old school, those practitioners who believe that the purpose of psychotropic medications is to make people who were otherwise unreachable able to benefit from psychotherapy. In recent years, and under the pressures applied to physicians, such medications have routinely become an end in themselves and therapy a luxury for which few psychiatrists can afford the time. Dan never succumbed to those pressures. In addition to his administrative, consulting, and volunteer services over the years to numerous institutions and facilities, including serving as chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Cottage Hospital in the 1990s, he remained at heart a therapist.

Because Dan was the soul of professional discretion, who disclosed little about his practice and never any information about his patients, I was not fully aware of how beloved he was by so many. Knowledge of his passing was limited to family and close friends, in keeping with his being a very private individual, but I placed an announcement on his phone to advise patients of his death and where their files were being held confidentially and available for forwarding to another doctor. The messages left and cards sent were remarkably touching. Several expressed not only their condolences to his family but also remarked on his having “saved their lives,” “been their favorite doctor,” “helped them through crises in their lives,” or “someone whom they could never replace.” One former patient commented that Dan would forever be on his shoulder and available to provide advice and direction.

While I know that my loss may involve pain that is unique to life partners after one dies, patients who have come to depend on a psychiatrist to help them navigate through their life also face a profound loss. Their messages gave me a glimpse into how important Dan had been to people within a part of his world that was largely unknown to me. We grieve his passing together.