Review: Invisible Realms

Contemporary Art and the Sacred at Westmont

Invisible Realms, a new group exhibition at the Westmont Ridley-Tree Museum, takes as its point of departure the fact that many contemporary artists connect with the sacred without employing traditional religious subjects, genres, or media. Using video, abstraction, appropriation, assemblage, and performance to make their statements, the works on display in Invisible Realms point beyond themselves toward some more elusive experience or state of being. Encountering them, one sees the influence and senses the presence of the sacred at a necessary remove. Like the German Romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin, these artists subscribe to the theory that, “near is / but difficult to grasp, the God.” Although the invisible realms of the sacred may remain impossible to finally locate or fully understand, art allows us to invoke their presence.

Director Judy Larson and her team at the Ridley-Tree Museum have done a wonderful job of installing the galleries. For example, the entrance hall to the larger gallery space forms an intriguing gauntlet. On the right are the rugged panel constructions of sculptor Michael Tracy’s “Dolores Suite,” a contemporary take on the Stations of the Cross that’s one part traditional Catholicism and three parts mystical scarification. The nails that protrude from the final pieces in the sequence resonate not only with the stigmata of the Passion, but also with the fetish objects of West Africa. On the left, keeping their distance from the nails opposite, but following Tracy’s same path of devotion, are Westmont faculty member Susan Savage’s radiant still-life paintings featuring silver bowls. The reflective surface of the bowls allows Savage to demonstrate the virtuosity with which she handles the complex perspectives that emanate from a convex mirror. But the bowls also serve as a way to draw the world outside into the picture; these are deeply poetic and philosophical images that reward sustained attention.

At the end of these walls and at a right angle to them, two video installations stand as the show’s Scylla and Charybdis, admonishing the viewer to abandon any lingering assumption that an exhibit about the sacred will be safe or conventional. Kent Anderson Butler’s “Submerged” and Hadassa Goldvicht’s “Kiss” deliver powerful messages through highly physical, privacy-invasive conceits. The artists both appear in their work — a fairly usual practice in video art. In the black-and-white loop “Submerged,” Butler’s head and naked chest appear upside down on the screen, half hidden in a bath of milk. Over the course of the piece’s run cycle, the artist takes a deep breath, sinks down under the surface of the milk, holds that position, and then reemerges to slowly open his eyes and smile for the camera. It’s unforgettable, and it is creepy.

In “Kiss,” Hadassa Goldvicht can be seen through a glass, darkly, on the other side of a panel containing a series of Hebrew letters written in honey. Slowly over the course of this loop the artist licks and sucks the honey from the panel. The pairing of these two works alone makes this one of the more interesting contemporary art exhibits of the season, and we are still outside the main room.

Once in it, the walls and floors overflow with the creative inspiration of nine strong artists, some familiar to Santa Barbara gallery goers, and others not so well known here. It’s a pleasure to see seven of Linda Ekstrom’s works involving the physical transformation of the Bible at once, and a testament to the open-mindedness and gumption of curator Larson that they are here in such force. Linda Saccoccio’s chakra paintings have never looked better, and they make a divine counterpoint alongside Father Bill Moore’s cross paintings. Mary Heebner’s Angkor Wat book is here, as are some of the most exciting drawings yet from Marie Schoeff.

Fabian Astore’s video with prayer rug, “The Threshold” from 2011, offers a glimpse inside Istanbul’s largest mosque during prayer time. The artist happens to have captured something unusual and anarchic from his covered alcove within the sanctuary, and while I won’t spoil things by saying what happens, I will say that “The Threshold” lends the exhibition some of its most purely joyful moments.

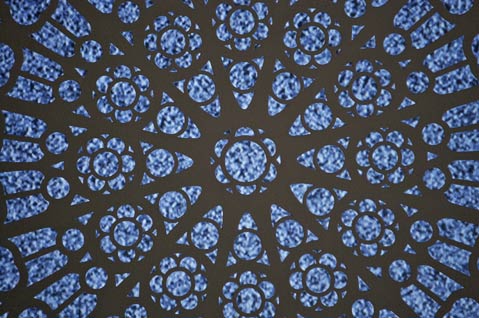

At the back of the exhibition’s inner room lies an installation by Adam Belt simply titled “Echo.” Inside this small white alcove one finds a miniature rendering of a traditional “rose” church window from the Basilica of St. Denis outside Paris. In “Echo,” the rose window form, ordinarily a vehicle for the soothing influence of light through stained glass, becomes the bearer of a field of video static, the kind of “snow” that used to plague pre-cable television sets. Intended to represent the energy given off at the creation of the world, the static implies even more than that; it’s a crystallization of the way that modern life continues to inhabit older forms of attention, an example of new wine in old bottles for the digital age.