Bob Kull’s New Book, Solitude

Ventura-Born Author Describes a Year Alone in the Wilderness

As a kid growing up in rural Ventura County in the ’50s and ’60s, Bob Kull spent a lot of time alone, exploring the creek beds, pastures, and coastline of the region. It was a way of being in the world that would call to him for the rest of his life. At 18, Kull left Southern California to travel the world in search of adventure, until in 1985, while working as a scuba diving instructor in the Dominican Republic, he wrecked his motorcycle. The accident cost him his lower right leg, and a year in the hospital forced him to reconsider what he wanted to do with his life.

At age 40, Kull enrolled in college as an undergraduate, embarking on a new project: that of linking his yearning for adventure with his hunger for intellectual stimulation and a burning desire for spiritual enlightenment. Facing the skepticism of his professors, Kull decided that the subject he really wanted to study was himself, and the way he wanted to do it was by living in the wilderness in total isolation from humans for one year.

Last month, New World Library published Solitude: Seeking Wisdom in Extremes, Kull’s collection of diary entries and commentary from his yearlong adventure in the Patagonia wilderness. This weekend, the author returns to the Central Coast to share his story.

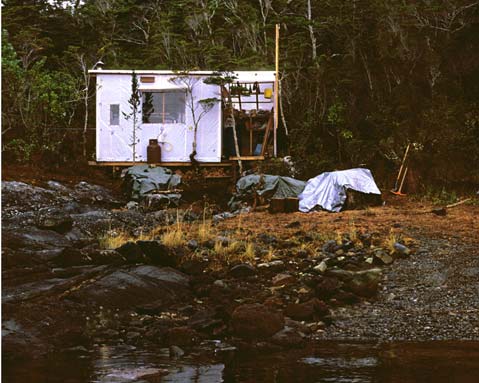

The location Kull chose for his retreat was a tiny island off the coast of Staines Peninsula, a rugged piece of land jutting into the Pacific Ocean on the remote west coast of Patagonia, near the southern tip of the Andes Mountains. The book’s introduction recounts the logistics required to get there: a yearlong process of list-making; the gathering of materials including building tools, camping and fishing supplies, food, clothing, and communication technology; visa negotiations, a flight to Santiago de Chile, a two-day bus ride to Punta Arenas followed by a six-week delay, a nearly disastrous truck ride to Puerto Natales, and finally, a 10-hour ride on a Chilean Navy patrol boat to his drop-off point.

Solitude is an unusual book. Like John Krakauer’s bestseller Into the Wild, it’s an examination of a man’s urge to live in wilderness isolation and the effects of such seclusion on the psyche; unlike that book, it’s a firsthand account, and its author has intentionally avoided dramatization. “I wanted it to be dead honest,” Kull said, speaking to me on the phone from Vancouver, where he now lives. “I didn’t want to mythologize it. I wanted to tell it as directly and honestly as I could, with all the ups and downs, so that the daily experience could speak for itself.”

To that end, the book is presented as a series of daily diary entries, framed by an introduction and epilogue, and interspersed with what Kull calls “interludes”: reflections written at a later date that attempt to put the diary entries in context. The result is a book that echoes the experience its writer endured. At times it’s exciting, at times frustrating, sometimes exhilarating, often mundane. It’s not particularly heroic. Mostly, it demands that the reader, like Kull himself, slow down and experience one moment at a time, without knowing where it will lead, or what will be gained.

Ultimately, Kull explained, learning to be present in this way was the enduring lesson of his year in solitude, if there was a lesson at all. “When we say, ‘What did you gain?’ in some sense I think that is a kind of an illusion,” Kull said. “Our culture is set up to think in terms of gain and loss, but what this process was about was letting go of that notion. I went to gain enlightenment, and eventually I let go of the idea of something to gain and instead surrendered and learned to be with the flow of life.”

The journal entry format of the book ensures that the reader will follow Kull along on the painful path toward such realizations, like when he slips on seaweed for the second time, cracking his shoulder blade against the rocks, or finds his boat flipped over after a storm, its motor submerged in seawater. Much of the book is devoted to the description of landscapes: the one of water, rock, and wind surrounding him, and the equally stormy emotional landscape within. “I think the endless rain is getting to me,” he writes at one point. “The tension I feel seems similar to the fear I’ve felt toward bears during wilderness retreats in Canada-as though something dangerous out there is coming to get me. But here there are no scary animals, just wind and rain. I suspect it’s mostly my own dark feelings I’m afraid of.”

When asked whether he ever felt at risk of losing his sanity, Kull was quick to answer. “Yep, absolutely,” he said. “That’s part of the process of solitude. Losing your mind is largely in my view a function of resistance, of not being willing to experience what is. The basic spiritual teaching is simply to be present. That’s the challenge, because we tend to run from experience we don’t like, or attack the source of it, or let it sweep us away and take us over.”

Though Kull clearly enjoys talking about the effects of solitude on the mind-he has a philospher’s eagerness to puzzle things out-humility makes him reticent about claiming to have discovered spiritual truths, or about prescribing such a quest to others. “I do recommend that we spend time with ourselves,” he said, “that we step out of our hectic daily round and come into a quiet place with ourselves as individuals. As far as recommending deep wilderness solitude, I never do. My sense is it’s a call from within. It’s hard. It’s painful at times, and it can be dangerous. To just kind of go on a whim; I’d never recommend that. I think those of us who are ready are ready when we feel that inner call.”

4•1•1

Bob Kull will discuss Solitude and sign copies on Saturday, November 1, from 3-4 p.m. at Tecolote Book Shop. RSVP by calling 682-2395. For more on Kull and his book, visit bobkull.org.