Standoff Over Psych Admissions Continues

No Direction Home

It has been one month since Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital closed its doors to Medi-Cal patients who seek voluntary admission to the psychiatric inpatient unit, known as 5 East. The shut-out resulted from a breakdown in negotiations between the hospital and Santa Barbara County over reimbursement rates for indigent patients. Under pressure from Prop 63 4 Me-a two-year-old advocacy group made up exclusively of clients of the county’s Alcohol, Drug and Mental Health Services Department-officials from the hospital and the county are only now making moves to resolve the situation.

According to Lisa Moore, Cottage’s vice president in charge of clinical services, it cost the hospital more than $800,000 out of its own coffers last year to treat county patients in 5 East. When the contract between the county and Cottage expired in July, the county offered 20 percent less per night of care, bringing Cottage’s anticipated loss this year to more than $1 million. In addition, said Moore, the county pressured the hospital to start accepting involuntary admissions again. “They said we won’t even negotiate with you unless you agree to take involuntary admissions,” said Moore, “but we aren’t able to because we don’t have room.”

On average, about 17 patients stay at 5 East, and there are only 20 beds. The hospital takes in an average of four county clients monthly, Moore said. There is also a shortage of psychiatrists in Santa Barbara, and involuntarily admitted patients require more intense psychiatric services. “We’re at an impasse,” said Moore.

On Tuesday, two women who are members of Prop 63 4 Me told the county supervisors that the situation was “unacceptable.” Bob Quinn, another spokesperson for the group, said that psychiatrically disabled people seek admission when they are in crisis, most commonly from depression, mania, or schizophrenia. If admittted, they typically stay in the unit for about three days, Quinn said, but occasionally for several weeks, during which time they receive a safe bed, support, psychiatric attention, and possibly adjustments to their medication.

The only alternative to voluntary admission into the Cottage psych unit is the county’s 16-bed facility for involuntary psychiatric admissions, called the Psychiatric Health Facility (PHF), which is located on the county’s Calle Real campus. This unit is “less humane,” according to one patient who has been to both: Patients are more violent, and the staff is quick to resort to physical or medicinal restraints. People are referred to PHF usually in response to police calls, and only if they are a danger to themselves or others, or adjudged to be “severely disabled,” a difficult standard to meet. Moreover, activists with Prop 63 4 Me are concerned about the stay in PHF becoming part of a criminal record or harming job prospects.

In the absence of the option of voluntary admission to 5 East, county mental health clients who come to the emergency room are still seen there by a team of psychiatric services staff members. They are sometimes able to find a vacancy in Ventura’s Vista del Mar Hospital. If not, they are sometimes turned onto the street, even if their condition is serious enough to meet the criteria for admission to the unit. More often than not, Mental Health Services clients are homeless, or living in shelters or in hard-to-get federally subsidized housing for people with low incomes. Frequently, their behavior while in crisis endangers their housing arrangments, according to Quinn.

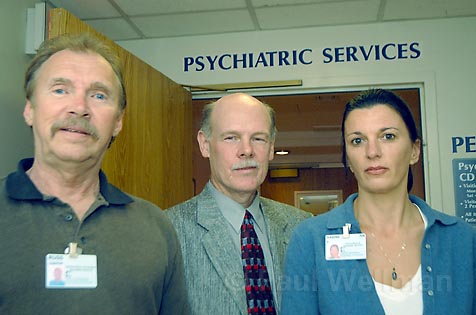

Doug Barton, interim director of Alcohol, Drug and Mental Health Services, reportedly told Quinn on Monday that he sent a letter before Cottage Hospital asked for a meeting but had not heard back yet. (Department officials could not be reached for comment, referring all inquiries to the county’s official press contact, William Boyer.) According to Moore, Cottage CEO Ron Werft will meet with Barton to resume negotiations, possibly before the end of October. On October 9, the Board of Supervisors approved a motion to put the matter on the agenda, though they did not set a definite date.