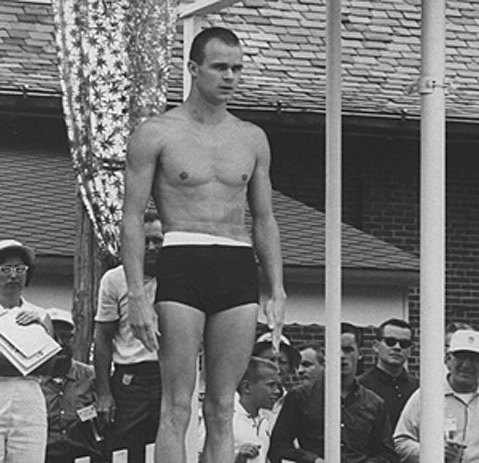

Olympic Mettle

S.B. Swimmer Gets Appendectomy Six Days Before 1960 Trials

When I woke up on July 27, 1960, I was in a bed in Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. My swimming coach, Bob Kiphuth, the legendary Yale and Olympic coach, was sitting across the room. As I came out of my anesthetic daze, the fuzzy details of the previous night’s events began to come back: waking up in my motel room about 4 a.m. with severe abdominal pains and passing out. My roommates called Bob, and we raced to the hospital. The emergency room doctor said I had appendicitis and would need an immediate appendectomy. I asked the surgeon how long it would be before I could swim, and he replied, “About six weeks.”

It had been a fast and frightening series of events, and Bob and I were thankful the operation had been a success and my appendix had not ruptured. But we were both thinking that the bandage that covered the five-inch long incision was evidence that the surgeon had removed not only my appendix but also my dream of winning a gold medal in the Rome Olympics. The Games would begin in one month and the U.S. Olympic Swimming Trials here in Detroit would start in six days.

Until then my chances had been very good. That week I had won the 100- and 200-meter freestyle races at the National A.A.U. championships, setting American records in both. My 100 time–54.8 seconds–was the fastest time in the world since John Devitt set the world record of 54.6 in 1957. Sports writers called me “the fastest swimmer in the world” and, as Bob Kiphuth was quoted, I was “… a shoo-in to win at Rome.”

I had trained under Matt Mann at Oklahoma but assumed my swimming career ended when I graduated and went into the navy. Then I was invited to go to Yale to train with other navy swimmers under Bob Kiphuth. I trained hard, in the gym and in the pool, and realized I was capable of being the best. In a year I broke 23 American and world records.

But my goal of an Olympic gold medal in the 100-meter freestyle now seemed out of the question. The Olympic Trials would begin in six days.

When the anesthesia wore off my right side hurt, but the big hurt was a pain in my heart. I had been defeated, not by another swimmer, but by an inflamed appendix. For me there would be no Olympics. Despair and self-pity ate into me until I cried. Then, with acceptance, the pain eased.

The day after the operation, I noticed Bob whispering to my doctor. When I asked what they had been talking about, he said, “I told the doctor you’re in magnificent physical condition and asked if you could try some post-operative physical therapy. You could start in the physical therapy room down the hall this afternoon. And there’s a pool in the hospital basement. You could go there tomorrow if you want. You might as well try to stay in shape; you’ve got nothing else to do here.”

Since Bob encouraged me, I agreed, even though I knew I would never make it to Rome. Nevertheless, I did feel that Bob had been rather conspiratorial with the doctor. Did he think that I might actually be able to recover in time to swim in the Trials, now only five days away?

Another thing that encouraged me was the tone of some of the telegrams I received, implying I might recover fast enough to compete in the Trials. Like this one:

JEFF: WERE ALL THINKING ABOUT YOU AND HOPING FOR A WORLD RECORD RECOVERY IF ANYONE CAN MAKE IT YOURE THE ONE

–ARLIE SCHARDT AND THE SPORTS ILLUSTRATED STAFF

That afternoon I did some light exercises to test my tender abdominal muscles. These exercises, and walking, were painful. So was swimming, if you could call it that. The next day, in the small basement pool, with Bob and the doctor supervising, I eased into the water, my stitches sprayed with plastic and my waist heavily taped. I walked in the shallow end, then floated, gingerly moving my arms. I was unable to kick because of the strain on my abdominal muscles. I was also a bit afraid.

Eventually I could dog paddle, but the effort tired me, and the stabs of pain worried me. I was a long way from winning a place on the Olympic team, and my disappointment was barely eased by Bob’s optimism: “We have almost a week before the 200 freestyle prelims. You can expect a great deal of improvement between now and then.”

When I finished the last hospital workout, on the eve of the Trials, I asked Bob about entering the 100-meter race. Had it taken place that day, I would have had no hope. But, considering my daily improvement, Bob did not rule out the 100. He said, “In the morning, before the first heat, let’s do a 50-meter time trial, to see how your speed is. Then we’ll decide.”

The next morning I checked out of the hospital and went to the pool. After a few warm-up lengths, at a discreet signal from Bob, I gently dove in and swam a 50-meter sprint. Bob’s wide grin when he showed me the watch told me I had not lost much speed. The turning point was reached: we decided to keep me in the 100.

The Olympic Swimming Committee had held at least one meeting about my participation at the Trials. The assumption was that I could not swim fast enough to qualify at the Trials, but that I could possibly recover before the Games. So they had one concern: how to get me on the team without my swimming in the Trials, which would be a violation of the primary rule that in order to be put on the team one had to participate in the Trials. Ray Daughters, committee chairman, later told Time magazine, “We wanted him badly.” They decided I would be the perfect test case for an exception to the rule.

So, before my first race, they told me that if I did not compete in the Trials, just prior to leaving for Rome they would allow me to race 200 meters against the slowest relay qualifier, and whoever won would be on the team as a relay swimmer. But I didn’t want to be given special consideration to make the team. The thought of someone making the team here and then losing his place in a couple of weeks was unfair. Also, I wanted to swim in the 100 at Rome, and making only a relay spot would not have permitted me to enter the 100. So I declined their offer.

My heat was called. As I walked toward the starting blocks, Ray Daughters approached me and said, “Jeff, would you please sign this before you swim?” He gave me a hand-written waiver of responsibility protecting the Olympic Swimming Committee and the Trials organizers in case something would happen to me as a result of competing in the Trials. The document had obviously been prepared in a hurry, and I thought their ill-timed approach was clumsy, but I signed.

Olympic starting blocks are higher than I was used to, and it hurt a bit when I climbed up. As the starter called, “Swimmers take your marks,” I bent over as much as the tight bandage permitted. Two swimmers jumped the gun, and I had to strain to keep from falling in.

The next start was good, and I dove gently out and down. At that moment mind conquered matter and all pain ceased, my thoughts of the race preventing any other signals from reaching my brain. As I reached the end of the 50-meter pool I automatically prepared myself for a flip turn and just did it. The push off the wall brought some pain to the edge of my mind, but the realization that the race was half over drove it out. I won my heat and easily qualified for the semi-finals. I won my semi-final heat in 55.6 seconds, the fastest of all the swimmers.

The finals were held the next evening. The stands were full, and it seemed that most of the people were there to see me make the team. Excitement and tension filled the air. Yet, for the first time in my career, I was not apprehensive. I knew that, after all I had gone through, I couldn’t help but finish in the necessary top two places and go on to win the 100-meter gold medal in Rome.

When the gun went off, I again dove slightly deep but quickly caught up with the other swimmers. By the 75-meter mark I was in excellent position for my final sprint; since training with Bob this had become the strongest part of my 100-meter race. Then, about twenty meters from the finish, overconfident and not concentrating, I closed my eyes (we had no goggles then) and swam into the lane line. I fell behind and couldn’t make up the loss. I finished third, one-tenth of a second behind Bruce Hunter, who was beaten by Lance Larson.

My world collapsed. I had been so sure of myself that I was thinking about the gold medal in Rome rather than winning the first or second place here needed to get me on the team. The fastest swimmer in the pool, I had simply lost my concentration. I dropped onto the nearest bench, threw a towel over my head and wanted to cry. But no tears came. This time I had been defeated not by my competitors, not by my appendix, but by myself.

The next day Bruce Hunter offered to give me his place on the team. I knew Bruce well enough to know that he was sincere, but of course I could not accept his incredibly generous offer. He told the Olympic coach, Gus Stager, the same thing, and Gus would not permit him to give up his place for me.

I swam in the 200-meter preliminaries and semi-finals, qualifying for the finals. The fastest six finalists would go to Rome. Many of my friends had already made the team. My disappointment at missing in the 100 meters began to fade, and by the evening of the 200-meter finals, I was eager just to place high enough to make the team. A second approach from the Olympic Swimming Committee, offering a later race to qualify for the relay, was rejected without hesitation.

More telegrams arrived. The one that inspired me most was from a stranger:

YOUR COURAGE IS UNSURPASSED IN SPORTS IN MY HUMBLE OPINION YOU HAVE DONE MORE FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COMPETITIVE SWIMMING THAN ANY OTHER PERSON IN THE HISTORY OF THE SPORT MAY YOUR HEALTH MATCH YOUR COURAGE AND KISS THE GOLD MEDALS FOR ME

—FATHER OF THREE AGE GROUP SWIMMERS MAMES N SIMONS

The stands were again packed that night, and it seemed that even more people than before were there to see me make the team. I knew that I had to do it. And I did, finishing fourth out of the six qualifiers.

When I received my certificate naming me a member of the U.S. Olympic Team, every person in the stands stood up and applauded. I was overcome with gratitude for Bob, my parents, the doctors and the uncounted supporters who had willed me onto the team. I had made it. I would have no chance to win the 100-meter gold medal, but I was on the team.

In Rome I was named co-captain of the team. My 54.7 in time trials put me on the 4×100 medley relay finals team. On September 1, the finals of the two relays were held. I anchored both relays and we won both in world record times. And even though I had to watch the 100-meter freestyle finals from the bench, admittedly with regret, I knew that being there, participating, was what mattered.

I thought of then and have, on occasion since, recalled the words of Baron de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Games, displayed on the giant scoreboard at the opening ceremonies of every Olympics: “The most important thing in the Olympic Games is not to win but to take part, just as the most important thing is life is not the triumph but the struggle to have fought well.”