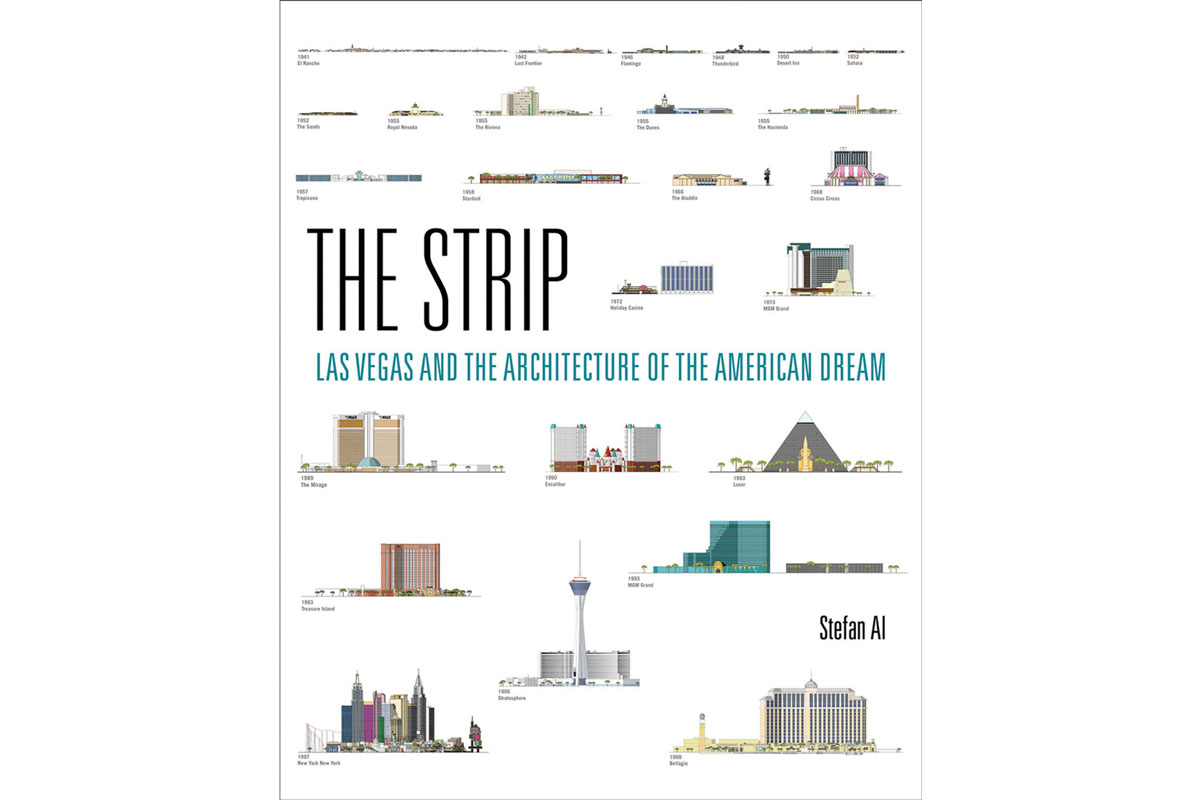

‘The Strip: Las Vegas and the Architecture of the American Dream’

Author Unclutters the Seeming Chaos of Sin City

A new visitor to Las Vegas, or even one who hasn’t been there in a decade or two, can’t help but be overwhelmed by the mélange of architectural styles thrust cheek-to-jowl against one another. Fortunately, Dutch architect Stefan Al is here with a new book, The Strip: Las Vegas and the Architecture of the American Dream (The MIT Press, 2017), to unclutter the seeming chaos.

Las Vegas has never had any trouble reinventing itself, so it’s relatively easy for Al to divide the architecture of the Strip into seven distinct phases. Older readers will remember casinos like El Rancho and the Last Frontier from the “Wild West” era (1941-1946) and the Flamingo and the Sands from the 12 years Al labels “Sunbelt Modern” (1946-1958). Middle-aged tourists will recall “Pop City” (1958-1969) and “Corporate Modern” (1969-1985) — think the Stardust, the Aladdin, and the Golden Nugget for the former period and the MGM Grand for the latter.

Younger visitors to Las Vegas will be more familiar with the Disneyfication of the Strip (1985-1995), as manifested in casino projects like Excalibur and Treasure Island. More recently, “Sim City” (1995-2001) has resulted in developments that recreate scaled-down versions of other places. There is the fake beach of Mandalay Bay, the diminutive skyline of New York, New York, the Eiffel Tower Experience, and, perhaps most depressingly, Sheldon Adelson’s The Venetian, where marble statues are reproduced in polyurethane and Styrofoam, and the simulated Rialto Bridge has moving walkways and “spans not the Grand Canal but a vehicular access road.” Al finishes with a chapter on “Starchitecture,” which showcases the work of renowned architects like César Pelli (ARIA) and Daniel Libeskind (Crystals mall).

The book’s thesis is that rather than being an architectural outlier, Las Vegas has always shaped, and been shaped by, the rest of America, “setting a template for practices of city branding, spatial production and control, and high-risk investment in urban spaces.” It’s not a particularly comforting thought, but by the end of The Strip it’s hard to disagree with Al’s conclusion: “Today, we all live in Las Vegas.”