Hot Buttons

GOP Contenders Must Decide If Tea Party Primary Support Will Play in General Election

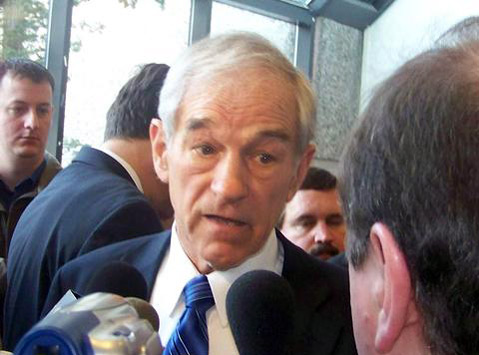

Representative Ron Paul was asked during this week’s Republican presidential debate how his fierce opposition to publicly financed medical care would affect an uninsured, 30-year-old man plunged into a coma by sudden illness or accident.

“But congressman, are you saying society should just let him die?” moderator Wolf Blitzer asked.

As Paul embarked on a lengthy answer, several loud voices rang out from the crowd watching the event, offering a clearer and simpler response:

“Yes,” let him die, they hollered. “Yes!”

The appalling incident was memorable, partly because it summed up the every-individual-for-himself tone and spirit of the right-wing Tea Party, the most vocal, energized, and engaged faction of the GOP. As a political matter, it also illustrated a stark dilemma facing leading Republican contenders: how to win enough support from the crucial, red-meat Republican bloc to secure the party’s nomination without turning off the independent and crossover voters, who will decide the general election.

The double bind is not a problem for Paul, the iconoclastic Texas libertarian whose candidacy is a sideshow, but it represents a big challenge for Texas Governor Rick Perry and former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney, the top two candidates, whose rivalry now shapes the Republican race.

In Monday night’s Tea Party debate, the second of five televised events within six weeks in which all eight Republican wannabes will face each other, Perry and Romney took decidedly different approaches. Simply put, Perry played to the demonstrative grassroots partisans in the Florida debate hall; Romney aimed his presentation at the larger and more diverse audience watching the event on TV.

Both in style and in substance, the two approaches reflect broader divisions within the GOP about ideology and the best strategy for defeating President Barack Obama next November.

Perry, since his recent, meteoric entry into the race, has quickly emerged as a Tea Party favorite: A full-throated advocate of their cut-taxes, slash-spending agenda, he also is a vocal social conservative on issues like gay marriage and strikes a fiery, combative, shoot-from-the-hip campaign stance. Romney, whose early lead in polls was quickly overtaken by Perry, also embraces Tea Party positions on taxes and spending; however, his sharp focus on fixing the economy eschews hot-button cultural issues, and his style is far more low-key.

Against all expectation in a Republican campaign, the sharpest contrast between them during the first two debates has flared over Social Security. With bravado and hot rhetoric, Perry has bashed the 70-year-old government pension system as “fraudulent,” a “Ponzi scheme” that steals money from younger workers for retirees; Romney pounced on the comments, supporting some reforms to Social Security, but portraying Perry as an extremist who is unelectable against Obama.

As a practical matter, the intense exchange over Social Security is disproportionate to problems with the system. Far from insolvent, it is fully funded until 2037; a projected shortfall, driven by retirements among the massive baby boom generation, could be addressed through a number of reforms that have been identified, from adjusting benefits based on overall income to raising the retirement age.

Far more than a fight over actuarial tables, however, the Social Security battle is a placeholder for a far more fundamental conflict about exactly what the Republican Party should stand for. While Romney supports tinkering with the system, Perry goes much further.

In Fed Up! — his campaign manifesto — the Texas governor described Social Security this way:

“A crumbling monument to the failure of the New Deal, in stark contrast to the mythical notion of salvation to which it has wrongly been attached for too long, all at the expense of respect for the Constitution and limited government.”

In an interview about his book, he added this question: “Why is the federal government even in the pension program or the health-care-delivery program? Let the states do it.”

The idea that the next president should work to dismantle the federal program underpinning a social safety net built in the decades since the New Deal is a decidedly radical notion, bespeaking a level of fundamental change in the role of government that many in the Tea Party support.

In selecting a nominee, a broader range of Republicans will be deciding whether they think that mainstream voters agree.