L.A.’s Risen at Sullivan Goss

Show Highlights Works by SoCal Artists, 1940-1990

Southern California has always been a place for innovation. Yet the bright lights of Hollywood have often obscured the full range of the region’s artistic output. Now, more than a decade into the 21st century, art historians are turning their gaze back to the mid 20th to establish the significant role that Los Angeles artists played in the rise of modernism.

Currently on view at Sullivan Goss are more than 25 works by some of the key players in the L.A. art world from 1940 to the 1980s. Another 16 works will arrive at the gallery in early September.

Gallerists Frank Goss and Patricia Sullivan Goss launched their gallery in Altadena in 1984. From the start, their collections included a focus on California modernism. With the publication last year of Lyn Kienholz’s encyclopedic L.A. Rising: SoCal Artists Before 1980 followed by the Getty Foundation’s Pacific Standard Time, a program of exhibitions that will highlight the role of Los Angeles artists in 20th century art, Goss saw the perfect chance to emphasize his gallery’s ongoing role in collecting and showcasing many of the artists in question.

Like the region it represents, LA’s Risen is dazzlingly diverse and spans a lot of territory. Here you’ll find hard-edge abstract paintings by Karl Benjamin and Frederick Hammersley in which strict geometry and flat bands of pigment call to mind the neoplasticism of Piet Mondrian. Meanwhile, Hank Pitcher was painting representational landscapes—his “On the Tarmac” depicts the Santa Barbara airport in the early 1970s. Still others were tackling traditional subjects with a distinctly modern sensibility: Bentley Schaad’s “Pomegranates” reduces the fruits to planes of light and shadow; Dan Lutz’s formal portrait of a seated man dissolves into abstraction at close range, the paint applied in thick, hasty lumps.

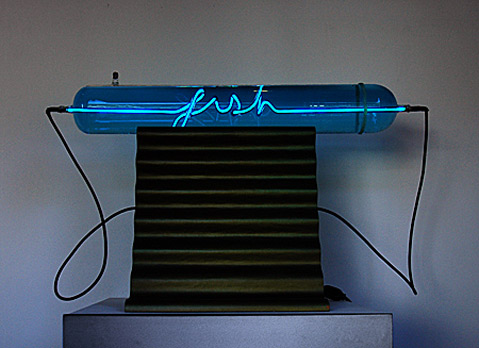

It’s another big jump from portraits and still-lifes to the three-dimensional works on display, among them Peter Zecher’s “Neon Fish.” The piece evokes a true symbol of the 1970s—the lava lamp—with a neon bulb casting its lurid blue glow from inside a glass tank. Across the decades, there’s a recurrent theme of painting as code. Knud Merrild’s “Abstraction 444” (circa 1935) is dense with dots and dashes; John Bernhardt’s “Radio Still Life” (1956) flays open this instrument of communication as if trying to decipher its mechanism; and in William Dole’s “Gesture” (1976), snippets of typography float between the stains and bruises of pigment like islands in yet uncharted waters.

If there’s a larger thesis at play here, besides the reminder that Goss has been in on the scene from the start, it’s that West Coast artists played an influential role in the art movements of the 20th century, whether or not they found themselves in the spotlight.