Challenging the Arts

Beyond Landscapes

When I heard that Rudy Ziesenhenne’s house, adjacent to the Santa Barbara Bowl parking lot, is to be torn down and replaced with 13 apartment units and 28 parking spaces, I attended the Architectural Board of Review meeting on the project.

It turns out that this transformation will require gouging out 3,350 cubic yards of the hill.

I suggested that Lowena Drive was too narrow to provide access to so many vehicles, that emergency vehicles would have a problem getting through when there are performances, and that the atmosphere of the bowl would be changed by losing that flowering hillside. But the person reporting on the Environmental Impact Study repeatedly insisted that there would be no significant environmental impact, and the project was approved.

I was surprised that the removal of 3,350 cubic yards of that little hill with its flowers, bushes, and trees would have no environmental impact. I imagined the roar of the bulldozers, loaders, and dump trucks handling that volume of soil and rock. I imagined the energy to be used in making and transporting all the cement and steel required to build those apartments. I imagined the traffic of the roughly 50 residents in 26 additional vehicles that will eventually use the narrow, curving Lowena Drive.

Obviously, my understanding of an environmental impact differs from the official version. I have been conscious of our deteriorating environment for decades. I wrote a pamphlet (“The Viable Culture,” 1990) about those aspects of our society that weaken our response to environmental challenges. I have watched the sprawl of development cover mile after mile of our agricultural land and the decline of species worldwide.

Of course there are still a lot of trees in Santa Barbara and some of the steep little gorges carved by streams are close to their natural state. But the continuing acceptance of growth shows that we are clinging to old values and the culture of exploiting our property as we see fit.

This is an echo of our situation vis-à-vis climate change. Although climate change is one of the greatest challenges humankind has ever faced, we find our government in a sort of trance, lacking the will to do what is necessary. We continue to burn fossil fuels as though there were no tomorrow—which, as a result, is becoming more possible. Our individual exertions are the beginning of a new direction, but cannot in themselves accomplish the prompt cutback in CO2 that is essential to preserving a livable climate and the continuation of our agriculture.

The fundamentals of our culture remain the same, in spite of much environmental education including Al Gore’s famous The Inconvenient Truth. For thousands of generations we have proceeded on the assumption that more is better and that it is only natural for humans to exploit nature and all of its gifts. The result of this culture of exploitation is that we are still are cutting down forests in order to create palm oil and soybean plantations, and to access the oil sands beneath the trees of the Boreal forest, destroying the plants that sequester CO2.

To create a sustainable lifestyle on planet Earth, we need a new culture based on understanding and embracing our relation to all living things. The creation of this new culture is the great challenge of the century.

Which brings me to the subject of painting.

Today, the painting that is considered contemporary is too often based on the theory that the significant art of any period could only have been done in that period. This simplistic view of art has resulted in a shallow, attention-seeking art that reflects the technical virtuosity of America today, while ignoring esthetic quality, human values, and aspirations. In other words, like much of our society, it lacks vision.

Many of those who are most concerned about the environment paint landscapes. But this appreciation of the natural world does not significantly affect our attitudes toward it. What we need is a new way of showing people in the landscape—people in relation to nature that is no longer a marvel, or a peaceful interlude, or a backdrop for human activities (e.g. Dejeuner sur l’herbe) but a full-fledged partner of human life.

In biology books, one finds diagrams of various cycles, shown with arrows tracing oxygen from green plants to inhalation by humans, while the carbon dioxide exhaled by humans becomes the leaves and branches of the trees. This cycling, this interdependence is the reality of our lives, a reality that must become deeply embedded in our consciousness, if we are to survive.

The artists who accept this challenge will find different ways to express the dynamic symbiosis between humans and nature. Some will paint the bulldozers leveling trees, others will find their symbols in people picnicking in our beautiful parks. Still others will paint the fruit pickers in the orchards or the farmers in their fields. The essence of this awareness may be in the interactive style of the art, rather than the subject. Perhaps interactions can be shown by blurring some of the edges, or by painting trees and people with the same vibrant brush strokes as Van Gogh did. Or some style that we have yet to imagine.

Controlling climate change and preserving the full range of life on Earth is the issue of the 21st Century. Those who pursue the creation of a new, sustaining culture will help to create a new world.

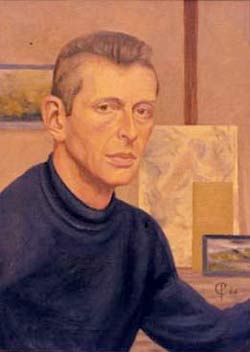

Peter G. Cohen, artist and activist, lives near the Santa Barbara Bowl. As a grandfather he is concerned about the world in which his grandchildren must live. His paintings can be seen at petergcohen.com.