Guy Delisle’s ‘Hostage’

Cartoonist Imagines Christophe André’s Kidnapping in Chechnya

In the late 1990s, when Chechnya was attempting to break away from Russia, a number of Westerners were kidnapped and held for ransom. Among them was Christophe André, taken from a Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF; also known as Doctors Without Borders) office in the neighboring republic of Ingushetia and held for more than three months. A few years after his kidnapping, he met French Canadian cartoonist Guy Delisle, and in the course of one long afternoon, Delisle recorded André’s incredibly detailed memories of his ordeal.

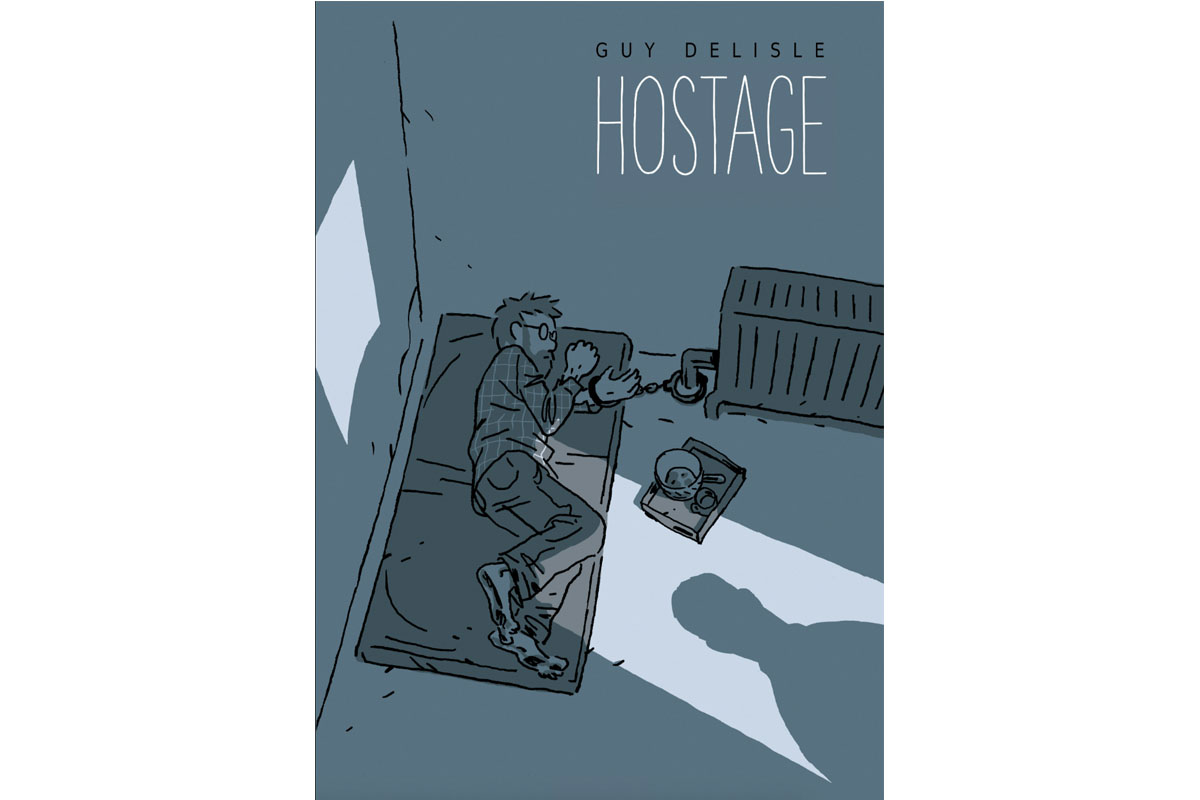

Fifteen years later, we have Hostage, Delisle’s imagining of André’s captivity. The majority of the book takes place in a single room, with a boarded-up window, a mattress, and a radiator, to which the protagonist is nearly always chained. Delisle uses only two colors in his 432-page book: gray and blue-gray. The book may sound (literally) monotonous, but readers of Delisle’s previous nonfiction works, which include the first-person travelogues Pyongyang, Jerusalem, and Burma Chronicles, know that the cartoonist focuses on small, seemingly prosaic details to build his narrative. Therefore, while Hostage is André’s story, through hundreds of skillfully crafted panels, Delisle effectively makes it his own.

During the course of his imprisonment, André has no idea what’s going on in the outside world. Are his bosses at MSF working to free him, or have they given him up for dead? Unlike many of the Chechens’ kidnapping victims of the time, André was rarely treated with violence; he was usually given two meals a day. Yet he was nearly always handcuffed to some immoveable object, making his solitary confinement particularly restrictive. Indeed, handcuffs are so important to the story that Delisle bought a pair and had a friend take “a bunch of pictures of [him] half-naked on the bed or on the floor” so that his drawings of the book’s most frequently drawn scene would be more accurate.

Other people might have quickly lost their minds in this situation, but André is remarkably patient and resilient. He’s a fan of military history, and he spends some of his endless hours reliving famous battles. He also displays a quiet but remarkable courage, as when he learns that his ransom has been set at $1 million. Talking to his NGO bosses on his captors’ cell phone, he insists the price is too high: They shouldn’t pay.

This declaration extends his imprisonment, but it’s in keeping with André’s steady sense of what is right and wrong. As Delisle no doubt intended, his protagonist is an inspiration. Often frightened and indecisive, André nevertheless persists in believing in a world beyond the present, demonstrating the fierce power of hope.