What’s on Your Plate?

The Social Justice Implications of Climate Change and the Food We Eat

Climate justice, food justice, and diet are all intimately linked: Our food system is one of the largest contributors to climate change — a global transformation that will have the greatest negative impact in areas where people already struggle with food insecurity and where most of an estimated two billion more people will be added to the population by 2050. At the same time, diet directly affects the health and wellbeing of all, whether food secure or insecure.

The world has experienced major shifts in diet in recent decades, and today most of us eat more calories, sugars, fats, animal, and processed foods than we did in the past, in both food limited as well as food abundant countries like the U.S.. This ongoing nutrition transition toward less healthy and more climate and resource intensive diets is a threat to climate and food justice because it leads to increased greenhouse gas emissions (GHGE), puts pressure on our limited agricultural resources and food supply, and is connected with a rise in noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.

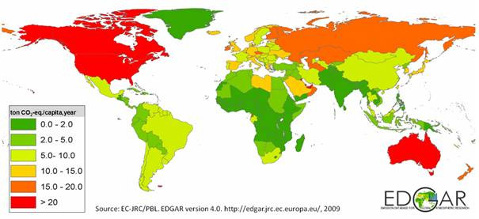

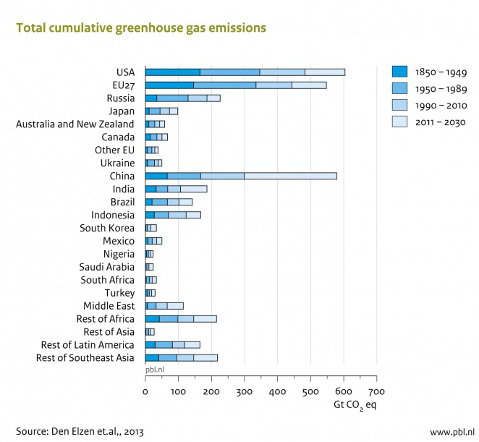

Climate justice requires that those who have contributed, and continue to contribute, the most to climate change should also do the most to mitigate it. To avoid catastrophic climate change requires not only making current human activity more efficient in terms of GHGE but also decreasing and then stabilizing the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. As the major GHGE producers over the last 200 years, Europe and the United States have a substantial responsibility to help those countries that will be most impacted by climate change (China will come close to US cumulative emissions by 2030). Santa Barbara County alone contributes about 5.3 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent each year, about 12.3 tons per person annually, which is 33 times the per person emissions in Bangladesh. And it’s poor countries like Bangladesh that are likely to be the most impacted by climate change, as well as the least able to manage the problem.

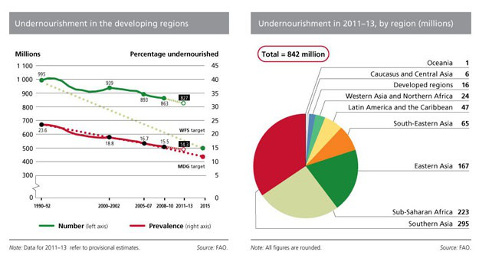

Food justice requires those who have contributed, and continue to contribute, the most to hunger and malnutrition do the most to mitigate them. According to the FAO (UN Food and Agriculture Organization), over 840 million people, or one in eight people globally, currently go hungry. This is not only due to the extreme and growing inequality in income but also to policy initiatives developed by the U.S. and Europe, which they pushed onto poor countries, leading to widespread food instability. At the same time, 1.4 billion adults globally suffer from being overweight and obese due to excess calorie consumption. In Santa Barbara County, 50 percent of adults in low-income households are food insecure, and 60 percent of all adults are overweight or obese.

On top of that, 40 percent of food in the U.S. and one-third of all food produced in the world is wasted throughout the food chain, contributing to food shortages. And wasted food hurts the planet in two ways: It is a waste of the food itself, and a waste of all of the resources used to grow, package, and ship the uneaten food and the work of farmers to grow it. Not only does wasted food contribute to GHGE all along the food chain, but much of this wasted food ends up in landfills, where it decomposes and releases more methane, a major greenhouse gas.

Diet change is an important way to tackle climate justice and food justice simultaneously. In fact, because our global food system contributes more than 30 percent of GHGE, there can be no climate justice without food justice. Diets of a minority of people in the richest nations (containing excess calories, sugar, fat, and animal and processed foods) contribute most to GHGE and to the growing scarcity of agricultural resources. Fortunately, recommendations for healthier diet align well with suggested measures for reducing the environmental impact of the diet, although the official USDA guidelines don’t go far enough. A recent study in the U.K. found that reduced red meat intake could reduce the risk of noncommunicable diseases by 3-12 percent and reduce GHGE by almost 28 million tons a year.

In general, we need to restrict the intake of calories to the amount we need; we do this by reducing intake of empty (therefore unnecessary) calories and animal-based foods, and replacing them with plant-based foods such as vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains. More sustainable and healthier diets have the potential to reduce GHGE because less food needs to be produced if overconsumption and food waste are minimized, and because minimally processed, sustainably grown, plant-based foods are less resource and climate intensive than animal-based foods. For instance, beef has a 13 times greater greenhouse impact than equivalent protein from plant-based sources such as tofu or lentils, and some studies suggest this difference could be even greater. Diet change has the potential of reducing GHGE and land use demands by 50 percent compared to our current diets.

Diet change for climate and food justice means changing diets of the most powerful and affluent in order to reduce GHGE and increase the availability of nutritious food for the least powerful. This will require supporting changes in food policy to discourage the current promotion of high-climate-impact diets for profit, and instead, make low-climate-impact, healthy foods affordable and attainable for the least powerful. Potential policies that could accomplish this goal include placing a value added tax on foods worst for the climate and health and providing incentives for farmers growing healthy, sustainable food.

Evaluating our food choices and “doing our part” is a first step to creating a more just world. So, how do we put these ideas into action on our own plates? Here are some suggestions, which we’ll explore in more depth at the Climate Justice conference this weekend (see below):

• Reduce our consumption of prepared, packaged and animal foods

• Prepare plant-based meals

• Eat seasonal, local, organic food

• Reduce food waste and compost the inevitable waste

• Support groups working to help the least powerful gain more control over what they eat, like our county and UCSB food banks, and those working to create a more just food system, that minimizes malnutrition and climate impact, for example, to reduce sugary drink consumption.

~

The Re-imagining Climate Justice conference takes place at UCSB on Saturday, May 10 from 9 a.m. until late. Please go here for full information on workshops, film fest, artwork, and creative space.

Along with other members of the Santa Barbara Agrifood Systems research group, we are hosting a session called “Climate Justice, Food Justice, Diet Change: Making the Connection, Taking Action” from 2:45-4 p.m. in the Ucen’s Lobero room that will make the link between climate justice, food justice and diet at the national and global levels, followed by a panel discussion with campus and community activists and the public, about how to promote diet change locally in ways that contribute to both climate justice and food justice.

The session will end with a demonstration of how to create delicious, low-cost, low-climate-impact meals, using locally grown ingredients. Participants will receive a sample menu with ideas and recipes.

Our goal is a highly interactive conversation about local solutions, involving a range of people from the community, including organizations working on climate, food, and environmental justice. Please join us.

David Cleveland is a professor in the Environmental Studies Program at UCSB. His book Balancing on a Planet: The Future of Food and Agriculture was published by UC Press in 2014.

Quentin Gee recently received his PhD in philosophy from UCSB and is currently a research scientist in the Environmental Studies Program at UCSB.

Elinor Hallström is an advanced PhD student at Lund University, Sweden, and currently a visiting scholar in the Environmental Studies Program at UCSB.

Amelia DuVall is an undergraduate majoring in Environmental Studies at UCSB.

Gerri French is a registered dietician who works as a diabetes and nutrition educator at Sansum Clinc and is the founder of Santa Barbara Food and Farm Adventures to support local farmers and sustainable food.