When I saw the headline about Elie Wiesel’s death on July 2, I felt as if I’d taken a physical blow. Had I been at home, I’m pretty sure I’d have lost the battle between the tears threatening to spill and my reticence to break down in public.

I met the late Nobel Laureate in 1981 when I was a reporter for the Los Angeles Daily News. Back then I was the only feature writer with a master’s in English and consequently had become the go-to reporter for authors on PR book junkets. I had already interviewed Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, John Gregory Dunne, and many others. And while each experience had an impact on me, my conversation with Elie Wiesel turned out to be one of the most meaningful experiences of my life.

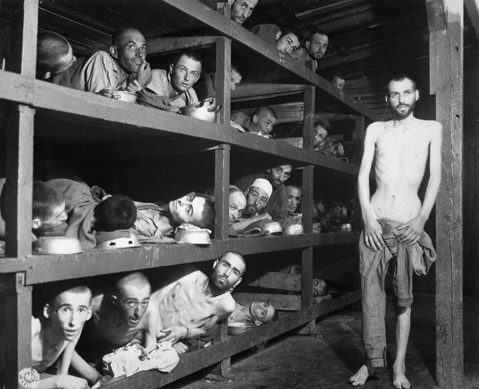

His story is now well-known. In 1944, the small, timid, and not particularly healthy 15-year-old was dragged from his home in Sighet, Romania, and, along with his mother, father, and sister, was sent to Auschwitz concentration camp. His mother and sister were immediately murdered; his father slowly wasted away. After being transferred to Buchenwald, the young teen somehow survived, and when the war ended, he was sent to an orphanage in France. There he took up intense study of Jewish history and law and later attended the Sorbonne. In 1956, he immigrated to New York City and lived there until his death.

Wiesel began writing in the ’50s, and in 1960 he published the English version of the renowned memoir Night, which went on to become required reading in many junior and senior high schools. Over his career, he penned some 57 works of fiction and nonfiction, mostly about the Holocaust and its atrocities. It is through these works that Wiesel is credited with providing the world with the intimate, personal descriptions of the horrors inside Hitler’s death camps that has led to the current meaning of the word holocaust.

Wiesel also became a teacher — a professor at the Andrew W. Mellon Center at Boston University, a visiting scholar at Yale, and a professor of Judaic studies at New York University. Always a tireless and outspoken advocate against all genocide and injustice, Wiesel was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986. The Norwegian Nobel Committee called Wiesel a “messenger to all mankind. His message is one of peace, atonement and human dignity” and said that his spirit was victorious over the “powers of death and degradation.” Wiesel remained politically active and one of the world’s most eloquent voices against inhumanity until his death.

I’ve always imagined that I got the assignment to interview Wiesel not just because I was the Daily News’ resident bookish writer. I’m Jewish, and I’m guessing that my editor figured sending me to cover the story made sense. Although I’m grateful she did, I was hardly the type of Jew who identified with the Holocaust. My family didn’t lose anyone to the gas chambers. And although I was forced to attend Confirmation classes as a teenager, I was a confirmed nonbeliever. In fact, being Jewish just made me scared. Any Jewish kid of my generation was hyperaware that another holocaust could happen — it was a point drilled into us.

To top it off, every year around Passover, my brother and I would sneak to watch horrifying documentaries on TV showing the aftermath of the Nazi killing machine: mind-boggling heaps of skeletal dead Jews, lampshades fashioned from dead Jews’ skin, teeth from Jewish corpses with the gold fillings removed, and so many other horrors that both my brother and I remain scarred to this day. On the rare occasions that we discuss our clandestine TV viewing, we both are quick to change the subject.

With these thoughts suppressed in my subconscious, I took on the interview. At that point, simply meeting a man who had lived through that nightmare filled me with awe, and I was truly relishing the idea of talking to Wiesel. I dove into The Testament, the story of a fictional Jewish poet in Soviet Russia who is assassinated by Stalin’s hit men along with all other Jewish intellectuals. Like much of his work, The Testament is both emotionally gripping and difficult to read. I prepared questions about the novel for the interview, but I knew I’d want to delve into far more than his narrative voice.

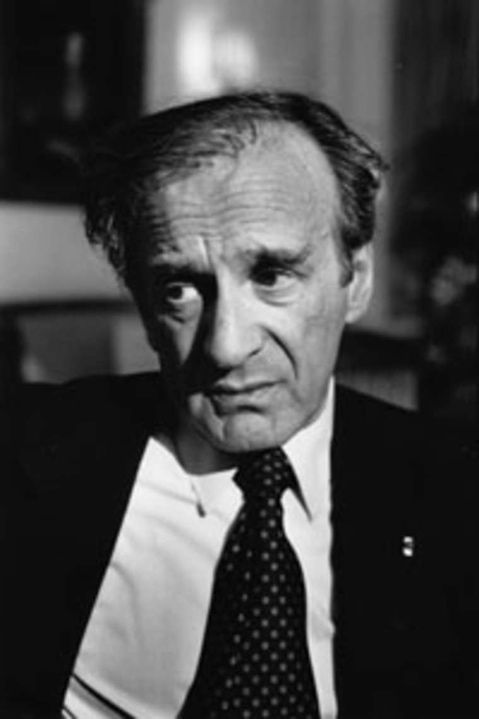

On the day of the interview, armed with a list of questions, I knocked on the door of Wiesel’s Beverly Hills hotel room. A middle-aged woman who introduced herself as his publicist opened the door. At 5’1″, I’m hardly a giant, but I found myself wondering if the tiny man before me was even shorter than I. Except for his face, he looked like a slouching teen. But that face had seen too much. Though he was only 52 when we met — my mother’s age at the time — he seemed much older. His eyes were warm, sad, and knowing all at once.

Soft-spoken, he emanated a power and dignity that hit me like a powerful drug. Something about this man was extraordinary. We quickly connected in a way that is rare, at least in my experience, and I felt as if I were speaking to someone great but as approachable as one of my parent’s friends. His publicist must have felt the link because she tiptoed out of the room. In my reporting experience, publicists stayed during an interview when they felt they might have to manage the conversation. That was not the case here. Wiesel and I were clearly fine on our own.

I noticed his prayer shawl, or tallit, and a small leather box containing Hebrew text Jewish men wear when they conduct morning prayers, tefillin, atop the TV. He was still a practicing Jew after all he had seen, I thought to myself. Then we began discussing his book. He said he didn’t write to write. “I don’t believe in art for art’s sake — as a student, yes. But now I believe art must relate to ethical considerations.”

I have always been drawn to why and how fiction writers produce something out of nothing, and this interview with a writer was no different. He told me The Testament is based on actual facts and took him 15 years to write, and that he considered writing a hobby. I learned that he wrote in French and that his wife translated his work and that he always kept a picture of Sighet in front of him as he wrote because “that is where it all began.” His words were punctuated with deep melancholy, and as we discussed the storyline and characters in his book, his reason for writing became clear. He admitted that the past haunted him. “When a Jew cries, 20 centuries cry with him or her. We are a link in a chain, and there are always processions of people within us.” I realized that he was compelled to write to remind the world to never forget, his own brand of survivor’s guilt.

I finally asked the question that had been nagging at me. How does a person see what he saw, experience what he experienced, and still go on? How can that person not be bitter and angry every second of every day?

“Yes,” he said slowly. “There is anger. But not bitterness. How can one not be angry? I belong to a generation mutilated, humiliated, and betrayed. I feel people hate survivors. We disturb them. We are a memory. They know we know.”

But how did he survive? I prodded. “Faith,” he said simply. He told me those without it were the first to go. “I don’t have any,” I told him.

Our interview time was up, and I handed him my copy of The Testament to inscribe. Walking back to my car, I was filled with admiration, awe, sadness, and, oddly, joy. I unlocked the door, sat in the driver’s seat and, hidden from onlookers, broke down and sobbed. I opened the novel to see what he wrote. “Janet — I wish I were your teacher — be well, Elie Wiesel.”

I wish he had been my teacher, too. The world has lost a truly great man. Rest in peace, Elie Wiesel.

Janet Mizrahi has been a lecturer in UCSB’s Writing Program for 16 years.