Truth Strikes Out

Tall Tales and Outright Lies Permeate Ty Cobb's History

TY COBB: When Santa Barbara sportswriter Al Stump wrote about legendary baseball great Ty Cobb, truth struck out, page by page.

His sports pieces were so questionable that major publications such as Readers Digest, the Saturday Evening Post, and other magazines that had fact-checkers refused to run his stuff.

Stump’s books about Hall of Famer Cobb, “The Georgia Peach,” produced fence-rattling line-drive charges of lies, exaggerations, and dubious tall tales aimed at hyping up his book sales.

Stump portrayed Georgia-born Cobb as a raving, brawling racist who sharpened his spikes, all the better to strike fear in the hearts of players at the other end of his slides.

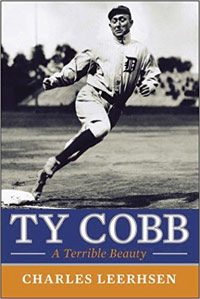

Cobb, arguably baseball’s greatest hitter, died in Atlanta at 74 in 1961, months after demanding but not getting corrections to Stump’s manuscript of Ty Cobb: My Life in Baseball, according to a revisionist 2015 book I came across recently by Charles Leerhsen, Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty.

“Stump took himself seriously as a writer and saw himself as a legitimate member of the vaguely Bohemian literary colony that worked and drank and lived at that time in Santa Barbara,” Leerhsen wrote.

“He often dropped the name of the well-known crime writer Ross Macdonald, the colony’s most prominent citizen.”

But Stump “had a reputation for inventing scenes and dialog and otherwise stretching the truth,” according to Leerhsen. He lost assignments to publications that had fact-checkers. That, Leerhsen was told by one successful writer of the time, “was because he produced fiction.”

I knew the group of 1960s writers Leehrsen is writing about. They met for lunch and were hardly “Bohemians” any more than small-town Santa Barbara was “Bohemian.”

Then there was the shotgun story. Stump claimed to own a shotgun Cobb’s mother used to kill Cobb’s father in a controversial 1905 shooting. After a collector acquired the gun, research showed that his mother had actually used a pistol.

Despite the many factual errors Cobb spotted in the first book, My Life in Baseball, it’s considered a fairly balanced view of Cobb, who never backed away from a fight back in his dead-ball era but took great offense at slurs that he sharpened his spikes into weapons.

Decades after Cobb’s death, Stump published two books, Cobb: The Life and Times of the Meanest Man Who Ever Played Baseball and Cobb: A Biography, that have been discredited as sensationalized and largely fictional.

Meanest Man and other Stump books became the basis for the 1994 film Cobb, directed by Santa Barbaran Ron Shelton, who specialized in sports movies (Tin Cup, Bull Durham, White Men Can’t Jump.)

In the movie, Leerhsen writes, “Tommy Lee Jones, playing the sickly old Cobb, attempts to rape a cigarette girl at a Nevada casino but fails to because of impotence.”

When he asked Shelton what the scene was based on, Shelton replied, “That actually was not in [Stump’s] screenplay … That is something that Al and I came up with during the shoot. It felt like the sort of thing that Cobb might do.”

When I emailed Shelton about this, he replied, “I did not make this up, as Leerhsen implied.” The incident was based on a story Stump told him, Shelton said.

Leerhsen quotes Shelton as saying, “It is well known that Ty Cobb may have killed as many as three people.” Pressed for details, Shelton told the author, “All this is well known.”

“What I said was accurate,” Shelton emailed me. “In the research we did nearly 25 years ago, there were numerous accounts of Cobb’s rage that may have led to killings.

“I was reporting on what was the accepted history at the time, and my research is in deep files by now … In a way the movie is more about Al Stump.”

By the 1970s, the baseball memorabilia market was becoming lucrative, and Stump went from selling supposedly Cobb-related items to outright forgery, Leerhsen writes. “Why not? He’d already created a fake Ty Cobb.” Stump, he charged, typed out between 50 and 100 letters using Cobb’s typewriter and trademark green ink. Experts later branded them as forgeries. One told Leerhsen that most Cobb autographs that collectors come across were actually written by Stump.

Stump died at 79 in Newport Beach in 1995, but the Cobb legend lives on.