Frimpong Case: Teeth Tell the Truth

Chapter Six of Joel Engel's Eric Frimpong Investigation

Read the previous chapter here.

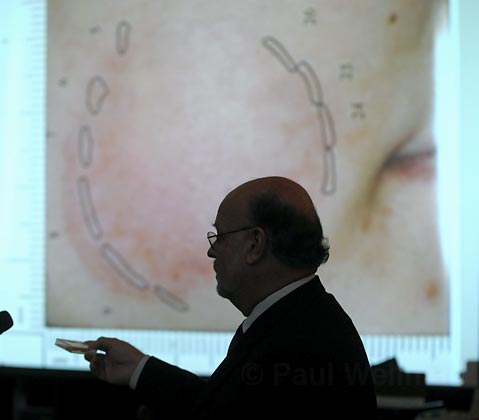

A few weeks before swabbing Randall, Detective Kies had approached Raymond Johansen, a local dentist with additional expertise in forensic odontology – the science and art of matching dental structures to other evidence. Accompanied by Santa Barbara Sheriff’s Department Sergeant Greg Weitzman, who knew the dentist, Kies had asked Johansen to compare enhanced photos of Eric’s teeth to photos of the bite mark on Jane Doe’s right cheek. When Johansen told Kies that the evidence was too “vague” to rule Eric in or out as the biter, Kies left and found a credentialed odontologist in San Diego, Norman Sperber, without filing a report on Johansen’s findings. This was a constitutional breach referred to as a Brady violation (case law: Brady v Maryland). The prosecution, which includes the police, is required to inform the defense of all exculpatory evidence.

By sheer accident, defense attorney Sanger discovered the undisclosed contact between Kies and Johansen shortly before Kies took the witness stand at trial, and Sanger sandbagged him on cross-examination. At first, Kies denied meeting Johansen before admitting that, though required, he hadn’t written a report of the contact. This soon led Sanger to move for a mistrial. During the hearing on the motion (which Hill denied), Weitzman, the property sergeant, asserted that the Sheriff’s Department hadn’t employed Johansen because he believed his fees would be too high compared to Sperber, who he claimed had agreed to work for “zero.” Sperber, however, did indeed charge for services – more, possibly, than Johansen would have, given that the county was on the hook for Kies and Weitzman to fly down to San Diego to see him, and for Sperber’s airfare, hotels, and expenses before and after trial. “I do not do this free,” Sperber testified. “I charge like every other forensic dentist does.”

Kies said he learned about Sperber from Senior Deputy District Attorney Ron Zonen, who according to the detective’s testimony knew of the contact with Johansen (“He said Dr. Sperber was much more credentialed”). But when Zonen was asked politely to come into court and, out of the presence of the jury, answer questions posed by Judge Hill, he denied having heard Johansen’s name and said that he’d not been apprised of the two-hour consultation until that very day. He claimed, “I didn’t have the impression that there was an analysis done. I wasn’t certain that Dr. Johansen – again, I didn’t know his name at the time – I don’t believe that he had – my understanding was he hadn’t even done any work at that time. It was purely a question of money.”

This is somewhat contradicted by Zonen’s additional comment that he had “known [Sperber’s] work for a number of years and I felt that he could simply do better at the job and had the better reputation and greater likelihood of qualifying as an expert.”

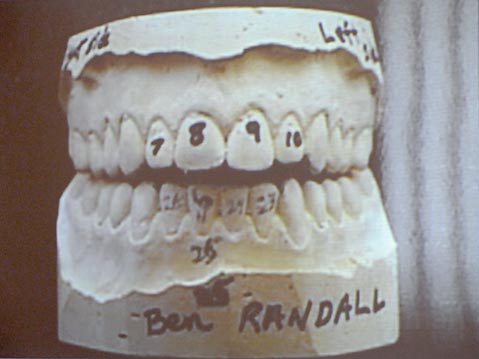

Bite-mark opinions are less scientific and more subjective than fingerprint evidence. Indeed, Sperber originally assessed the evidence to be lacking in “clinical detail” and therefore inconclusive. But, surprising the defense, when Sperber saw Randall’s bite mold that was made halfway through trial, he excluded Randall as the biter and included Eric in the universe of people who could have caused the mark. To counter that, Sanger hired prominent odontologist Dr. Charles Bowers. Bowers, though, was facing imminent surgery and didn’t have time to complete his analysis.

At the motion for new trial, Judge Hill said he would have granted Sanger a long-enough continuance for Bowers to recover and conduct a thorough exam. Sanger hadn’t requested one, though. Too bad for Eric. Bowers’s completed findings, presented as evidence for Judge Hill to consider in deciding the new-trial motion, supported Eric’s innocence and Randall’s culpability as the biter. He explained that Sperber had oriented the bite mark incorrectly and was therefore misreading the evidence.

Hill rejected the new-trial motion after dismissing the testimony by Bowers as not “credible,” despite the fact that Bowers is a diplomate, American Board of Forensic Odontology; a fellow of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences; and serves on the committee to revise and reform national professional standards for the interpretation of bite-mark evidence.

“It doesn’t take an expert,” Judge Hill said, “to be able to look at the photographs of the injury, the defendant’s teeth, Mr. Randall’s teeth to see that the top teeth are closest to the mouth of the upper teeth – are the ones that inflicted the injury closest to the mouth of the victim : “

Ironically, this contradicted the judge’s own instructions to the jury not to compare and contrast the bite-mark evidence themselves. “There’s no question in my mind that the more credible expert witnesses on this issue,” Hill said, “were Dr. Johansen” – who had been hastily called into court to answer questions about his contact with Kies – and the prosecution odontologists.

So in the judge’s own opinion, Johansen’s testimony could have been a game changer if Sanger had known about him either as a substitute for Bowers or to bolster his findings. We know that because earlier this year we asked Johansen for a complete odontological assessment. His report concludes: “Due to the inconsistencies between the relationship of teeth #’s 24, 25, 26 and the relationship between teeth #’s 8 and 9, Mr. Frimpong can be ‘EXCLUDED’ [sic] possible biter in this case.” And: “Due to the consistencies noted above and especially the relationship similarities between Mr. Randall’s teeth #’s 24, 25, 26 and the bite mark pattern in that area, Mr. Randall is ‘INCLUDED’ in the population of people who could have made this bite mark” [emphases in the original].”

A bedrock on which the prosecution based its case was the conclusion that the biter was the rapist. Johansen’s testimony pointing to Randall as the possible biter – and, more importantly, excluding Eric as the biter – would therefore have injected at least a tincture of reasonable doubt into the jurors’ minds, leading quite possibly to an acquittal. This made Kies’s intentional failure to disclose his contact with Johansen, which prevented Sanger from employing the dentist as his expert witness, an unconstitutionally fatal strike against Eric.

Read the next chapter in this serieshere.