The Outsiders

New Voices Seeking Spot on City Council

Every two years, Santa Barbara voters find themselves confronted by a host of mayoral and city council candidates who did not rise through the ranks of established political organizations. Typically, these candidates don’t generate much, if any, campaign cash. They garner few, if any, political endorsements. Realistically, their chances of victory are, at most, remote. These are the outsiders. But they bring to the race a truth to tell and the courage of their convictions. Sometimes, they address thorny issues that mainstream candidates won’t. Often, they speak with a blunt humor or open anger that the well-schooled have learned to avoid.

Theirs is a lonely crusade, but their presence helps measure the political temperature of the body politic. This year there are far more outsiders than usual. But there are more candidates – 18 in all – this year than most, reflecting perhaps a generalized disgruntlement with City Hall, the recession, and the status quo. Forums have become so unwieldy that on occasion candidates find themselves limited to mere yes and no answers. Some outsiders insist they’re in the race to win. Others consider will declare victory if they succeed in raising their issues. And others are happy just to find a microphone and a crowd to talk to.

FOR MAYOR:

BOB HANSEN: At age 62, mayoral candidate and homeless advocate Bob Hansen has graduated from class clown to court jester, injecting local politics with insightful commentary, disjointed ramblings, street theater, a few personal attacks, and (very occasionally) a song. Now waging what he reckons is his eighth race for public office – like the number of times he’s been arrested – Hansen focuses on the plight of the homeless. He’s quick to dismiss concerns about aggressive panhandling as part of an anti-homeless “witch hunt.” If it’s so bad, Hansen asked, why have the police issued only five aggressive panhandling citations in the past five years? “I’m not saying it doesn’t happen, but mostly it’s the young kids who dress all in black,” he said. “Most homeless here have learned they need to hold a sign and look pitiful.” Instead of the much heralded “12 point” or “10-year” plans to deal with homelessness, Hansen said, Santa Barbara should open some of the city’s many empty buildings to the homeless. To keep them manageable, he said, such make-shift shelters should be limited to 25 people, not 200.

A homeless advocate since the 1980s, Hansen is keenly aware that many have concluded there’s no solution to the homeless problem. “Some things do work,” he insisted. “The El Carrillo [transitional housing complex for the homeless and mentally ill] works. It’s a roof over your head, a place to call home.” With 25 homeless dying on the streets this year, Hansen said, what doesn’t work is the raft of rules and regulations imposed at the Casa Esperanza homeless shelter, which he claims effectively denies services to people in need. What doesn’t work, he said, is the chronic dearth of mental health beds in Santa Barbara County – only 12 on the South Coast. “That’s just rank,” he said. He also took exception to the growing popularity of “Greyhound Therapy,” in which homeless people are given one-way tickets out of town. Hansen acknowledged, however, that such tickets are given to homeless in hopes of re-uniting them with friends or relatives, not simply getting them off Santa Barbara’s tourist-dependent streets.

Hansen has embraced Measure B, the proposed charter amendment to reduce the maximum building heights in town, but admits he did so in part to goad mayoral candidate Dale Francisco’s. “I got tired of hearing Dale say he was the only one to support Measure B,” Hansen admitted. As to the merits of the measure, he said there’s more to preserving Santa Barbara’s architectural heritage than mere height limits. “It’s more about set-backs and creating green spaces,” Hansen said. In the meantime, Hansen is delighted to annoy Francisco, whom he claims has a harsher and more punitive attitude towards the homeless. When Francisco first announced he was running for mayor, Hansen was on hand to heckle, both loudly and relentlessly. To that end Hansen is asking all his supporters to vote for mayoral candidate Helene Schneider. “I don’t always agree with her, but at least she’s not using the homeless as a hate and fear kind of thing.”

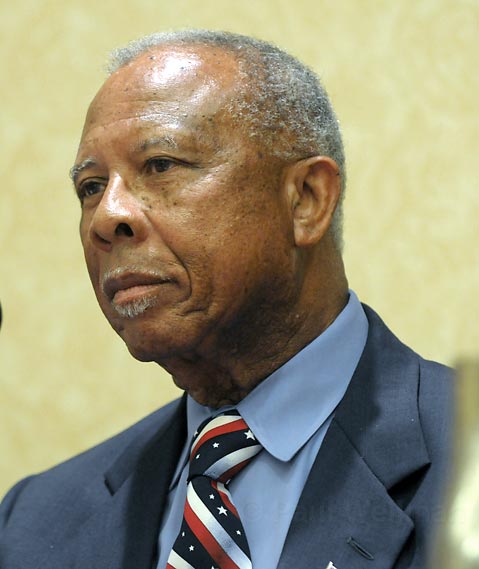

ISAAC GARRETT: Having run for city office twice before – once in 1969 and once in 2001 – Isaac Garrett’s hoping the third time will prove the charm. Graced with a quiet dignity, folksy charm, and deceptive humor, Garrett is running for mayor because, he says, none of the other candidates understand how the office should be used. It’s much more than being “chairman of the board,” he said. As an example, Garrett noted how Congress member Lois Capps was slow to convene a community forum on health care reform. “As mayor, I would have convened a town hall forum and presented the results to Capps. If she ignored those results, I’d let her know that I would publicly campaign against her when she was up for re-election,” he said. “For too long, when local politicians go to Sacramento or Washington, they get in bed with the party bosses.”

Garrett, who moved to Santa Barbara from Louisiana – by way of Michigan and Florida – in 1960, has a long active history with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, over which he presided for six years. In 1991, he served on the Grand Jury. Then, he sought to investigate allegations that the District Attorney applied a double standard in the prosecution of certain offenses. The presiding judge, however, reused to sign the subpoenas necessary to compel county prosecutors to testify and the investigation went nowhere.

What pushed Garrett into the race, he said, was the city council’s decision to give general employees a 2.5 percent pay increase “right in the middle of a budget crisis.” He said City hall needed to enact an immediate freeze on all discretionary spending, and determine which services are essential to city government. Police, fire, water, and roads were essential, he said; day care, he said, was not. Public employees unions, Garrett concluded, had too much political clout. Garrett has made campaign finance a centerpiece of his race, though he readily concedes there’s little that can be legally done to limit campaign donations. He expressed concern that the $50,000 donation mayoral candidate Steve Cushman received from Russian banker billionaire Sergey Grishin would create, at the very least, a perception of conflict. He suggested candidates should voluntarily submit to campaign donation caps. In his case, Garrett is not accepting anything more than $500. He said so many outlets exist for candidates to get the word out that they need not pay through the nose for radio and television advertisements. “If people are interested, they’ll find out,” he said. “If they don’t make the effort, they’ll screw up the elections themselves.”

Garrett said City hall has failed to wage an effective campaign against gangs, and has suggested that City Hall begin seizing the properties where active gang members reside, much the way law enforcement agencies now seize the property of suspected drug dealers. “I’d be willing to give a perpetrator an opportunity to renounce his gang membership before we get that point,” he added. Like wise, the landlords and parents of active gang members should be given every opportunity to abate the problem before the hammer dropped.

While Garrett signed the petition to put Measure B – the building height restriction – on the ballot, he remains adamantly opposed to it. The Chapala Street buildings that gave rise to Measure B, he said, should never have been built. “But that’s because the people who had the responsibility for saying no were negligent in the execution of their duties,” he said. Garrett said ballot box legislation rarely works. “There are always unintended consequences. If you passed an ordinance and there were problems down the road, you can amend the ordinance. But if you pass a charter amendment and there are problems, you’re pretty much stuck.”

FOR COUNCIL:

BONNIE RAISIN: Bonnie Raisin doesn’t have to read about Santa Barbara history. She’s steeped in it. Her grandfather, William Preston Butcher was the city attorney who wrote the city’s first modern book of codes and ordinances. Her father, William P. Butcher Jr., one of the town’s most storied criminal defense attorneys, was appointed municipal judge in 1960 by then Governor Jerry Brown. With this lineage, it was almost inevitable that Raisin would gravitate to public office. “I woke up one morning and said ‘I’ve got to do this,'” she explained. Santa Barbara, she said, is becoming increasing elitist. City Hall has grown disconnected from the neighborhoods, she said, and newcomers are trying to freeze Santa Barbara as they’d like it to be rather than what it actually is. “They don’t understand we are a small city, that we have an urban complexion and that we have the problems of many urban areas,” she said. “They don’t want to accept this; they want to create Santa Barbara as an image of something I think is impossible.”

The “they” in her estimation are the people supporting Measure B – the ballot measure that would reduce the maximum allowable building heights by one-third – and many of the new breed of Republican activists, like mayoral candidate Dale Francisco, who want to keep Santa Barbara as it is. Raisin opposes Measure B. “We already have so many design review boards and commissions in place to disallow just about anything,” she said. “Besides, I look at variations in building heights and think, ‘It’s so beautiful; it’s wonderful.” Raisin – herself a card carrying Republican for the past 20 years – said much of the concern about aggressive panhandling seemed overblown. “I don’t see tourists saying, ‘I’m not going to Santa Barbara.’ There’s so much fear out there: ‘It’s all the homeless people.’ But it’s economic; it’s much easier to point a finger at a homeless person,” she said. “The fact is beggars existed before time and we’ll always have people who don’t want to live like you and me.” As for gangs, she said they’re a real problem but credited the police for doing “a darn good job” dealing with them.

Raisin spent 18 months working as a drug-and-alcohol counselor at the Casa Esperanza shelter. Before that, she worked at Devereux School, and she sold real estate many years prior to that. During the 1980s, Raisin was politically active through the Association of Realtors and the Republican Party. She remains very much a fiscal hawk, who would work to cut salaries and benefits before closing down a fire station.

In Raisin’s estimation, City Hall has few afflictions that can’t be fixed with district elections, in which council members are elected to represent a specific neighborhood. The current at-large system, in which council members represent the entire city, is structurally engineered to engender a disconnect between City Hall and the community. Failing that, however, Raisin said the council needs to embrace an intense regimen of town hall meetings conducted throughout Santa Barbara many neighborhoods to stay in touch. “What do I know about what’s happening on the East Side or the Lower West Side?” she asked. “The fact is I don’t.” For Raisin, it’s all about representative government. “This is a democracy,” she said. “Do we live it or do we just preach it?”

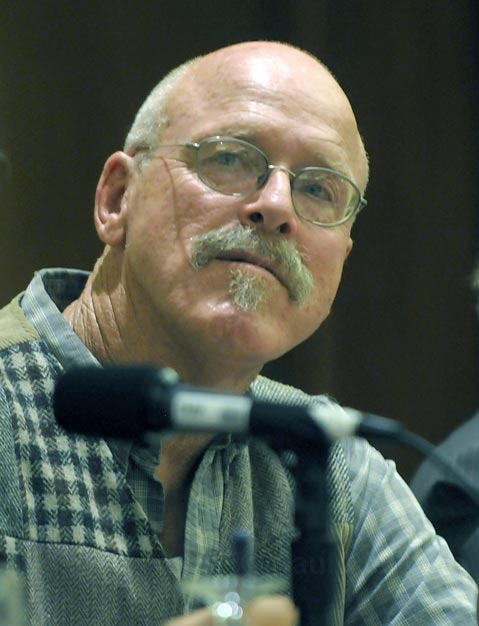

LANE ANDERSON: In his campaign for City Council, Lane Anderson isn’t taking any money. It’s not because he’s bashful about asking; it’s a statement of principle. Long before the specter of millionaire Texans or Russians hovered over this year’s campaign, Anderson was questioning the consequences of special interests bankrolling candidates. Real estate interests, he charged, offer candidates money if the candidates express a willingness to appoint real estate professionals to city boards and commissions. That’s wrong, he said. Because he hasn’t raised $5,000, Anderson – best known for his work with Veterans for Peace and as a co-founder of the Arlington West cross display at the base of Stearns Wharf – wasn’t allowed to participate in a candidates’ forum organized by the Chamber of Commerce and lodging industry.

Anderson jokingly refers to himself as “the leaf blower” candidate in this year’s election, but his palate of issues is much broader than whether the dust kicked up by gas-powered blowers poses a health hazard to people with respiratory conditions. For example, he said he was trying to midwife a collaborative venture between City Hall and City College to create a student dorm by Pershing Park. Because students can be packed four-to-a-room, he argued the creation of such dorms would alleviate the intense pressure students now place on the rental housing market, and actually help drive rents down. Because the dorms Anderson envisions would stand 50 feet high, he opposes Measure B, which would prohibit the creation of buildings taller than 45 feet.

Likewise, Anderson said City Hall can and should raise revenues in response to chronic budget woes, not just cut programs. He said the city should charge any businesses that sell alcohol a tax based on the risk those alcohol sales generates. “Alcohol is a most expensive drug,” he said, estimating that half the police department’s $34 million budget is spent responding to alcohol related problems. While the City of Santa Barbara has been reluctant to explore this possibility, the City of Ventura has such a program in place, and the revenues generated fund one full time officer.

Anderson has personal knowledge of the toll alcohol addition can take. He relates that he has been sober 31 years. Based on that experience, he stressed the necessity of finding clean and sober housing for homeless people, many of whom are battling addiction problems. He suggested that many homeless could be sent to former military compounds that are now vacant. Likewise, Anderson said that General Relief recipients should be required to find clean and sober housing.

It was in 1978 that Anderson, who served 14 months in Vietnam, moved to Santa Barbara, drawn by the ideal sailing conditions in the channel. He took a job with the Postal Service, and over time, he was elected union president, an experience that gave him first-hand knowledge of the nuanced intricacies associated with public employment contracts. An outspoken peace activist, Anderson retired 12 years ago. When George Bush declared War on Iraq, Anderson joined with other peace activists to start Arlington West along West Beach, which remains ongoing. When Anderson heard the city’s Redevelopment Agency had $3 million plans to repave the West Beach sidewalks and add new crosswalks, he was incredulous. “The current sidewalks are just fine. This is money we could be spending elsewhere on other things we need more,” he charged.

On gangs, Anderson said the community as whole needed to provide at-risk teens more and better opportunities. He cited his experience working with the high schools to create a Peace Academy, as a counter to ROTC, where leadership skills would be taught. Anderson also suggested property owners who dwell in high fire risk zones should be charged a pro-rationed share of fire protection costs. Such fees, he said, could be waived for homeowners who responsibly make their properties as fire resistant as possible. And Anderson is serious about leaf blowers. The city’s existing leaf blower ordinance has to be the least enforced law on the books, and Anderson contends the allergens and contaminants sent air born by the machines poses an entirely preventable health risk to many residents. However idealistic Anderson may be, he remains exceptionally realistic about his chances at the polls. That doesn’t faze him in the least. “I don’t have to win,” he said, “to win.”

JOHN GIBBS: One of Dr. John Gibbs’ claims to fame is that he invented the garbage bag rain coat. Just as he approached the football stadium in Madison Wisconsin, the sky opened up. He ducked into a nearby drug store and, finding no raincoats, snatched a box of industrial sized garbage bags, put one on and shared the rest with people down the aisle. The rest is history.

Since then, Gibbs, a man of barbed assessments and easy affability, moved to Santa Barbara in 1974, after having earlier driven through and encountering Fiesta in full swing. For 26 years, he enjoyed the life of a successful anesthesiologist. A pro-life Republican, Gibbs lived in San Roque, happily uninvolved at all in the political process. All that changed when councilmember Helene Schneider – and mayoral candidate – started promoting her “little blue line” project, Gibbs said, designed to show the effects of global warming on Santa Barbara’s water levels. To Gibbs, that was peripheral to Schneider’s city duties. When the economy tanked, that was the last straw. “There were seven people up there fiddling while Rome – Santa Barbara – burned,” he said. “I couldn’t take that any longer.” Gibbs doesn’t reckon his lack of experience is a hindrance. “It was the people who had all the experience who took us down this hole,” he said. “Besides, you don’t need to be a genius to serve on the city council. The learning curve isn’t that steep.”

The first thing Gibbs said he’d do is cut the council’s pay by 20 percent. That way, the council would have standing when it demanded the same of city employees. “It’s going to hurt, and if I was in their shoes, I wouldn’t want to do it,” he said. “But the council has to set the example.” (Gibbs expressed skepticism about recent bump in council salary. “It was supposed to attract better people. Instead we got the same people getting paid more,” he said.) Now is not the time to raise taxes or fees, as some candidates have suggested. To balance the budget, he said City Hall will have to make do with considerably less. If police officers, firefighters, and other highly paid employees leave, Gibbs was confident that qualified replacements would be ready to fill the void.

Gibbs emphatically supports Measure B. “It sends a subliminal message that the people who approved these structures [three recently constructed buildings along Chapala Street] don’t get it. It’s like the three blind men and the elephant – one feels the tail, another feels the trunk, but they don’t get together.” As far as Santa Barbara’s planning and design review process, Gibbs said it takes too long and that it’s marred by favoritism. On medical marijuana, Gibbs called it “a farce” that dispensaries could be located near to public schools or Girls Inc. “Marijuana will become legal, no doubt about it,” he said. “But it’s not the city’s job to be at the forefront.”

Of the mayoral candidates, Gibbs favors councilmember Dale Francisco, explaining, “He’s willing to take on the establishment.” Gibbs is not seeking contributions and is limiting his spending to no more than $1,000. He recognizes this makes him a very long shot. Still, he’d like the job. “I’m vain enough to think I can do it,” he said. “And I’m humble enough to listen.”

CRUZITO H. CRUZ: Where most candidates are quick to articulate outrage over gangs and youth violence, Cruzito Cruz is more horrified by what he terms “the penal industrial” complex, which puts Latino youth on the fast track for a life behind bars. A youth advocate, mentor, artist, accountant and mystic, Cruz speaks with a deliberate, if ornate, formality. He grew up on Santa Barbara’s Eastside, playing at La Casa de la Raza, taking boxing lessons from Primo Boxing’s Art Carbajal, and break dancing with Midnight Breakers in front of the Granada Theater.

He’s lived most of his life in an affordable housing complex run by the Housing Authority and attended both City College and UCSB. Gang violence, he acknowledged, is a real problem. But the problem, he said, is exacerbated by “racial profiling and the demonization of our youth.” City police target and harass Latino kids, he charged, placing their names in computerized gang data bases whether they belong or not. The more such names, the bigger the law enforcement grants. Over time, he said, a system evolves and perpetuates itself by tripping up young people, who discover that once in, it’s all but impossible to get out. “Let’s get them an education,” he said. “Let’s hold the educators accountable for not teaching their kids. We need more positivity. We need to create more prodigies and fewer prisoners. But as a society we’re willing to allocate more resources on enforcement, but not on education or jobs programs.”

As a councilmember, Cruz vowed he’d bring a different and necessary perspective to the table; he too has been harassed. Cruz said he’s been cited for resisting arrest no less than eight times, though he claimed he never fought back. In one instance, he sued the police department but lost in court. In all cases, he said, he paid his debt to society and his record’s been expunged.

Cruz cites his experience as student representative to City College’s governing board. But mostly, he talks about his most recent legal victory over City Hall. When the city clerk rejected half the signatures Cruz turned in to qualify for the council ballot, his candidacy seemed finished. Mayoral candidate (and councilmember) Iya Falcone had suffered a similar fate. All the legal experts told Falcone that a court challenge was futile. Falcone, a seasoned political pro, dropped out. But Cruz, acting as his own attorney, defied the prevailing wisdom and duked it out in court with City Attorney Steven Wiley. When the dust settled, the judge ordered Cruz’s signatures counted and he qualified for the ballot. At candidates’ forums, he frequently points to the voluminous stack of legal papers from this David-and-Goliath showdown to demonstrate his tenacity and determination.

On traffic calming devices like bulb-outs, one of the festering controversies of the race, Cruz is unapologetically and enthusiastically supportive. As a bicycle commuter, he said bulb-outs force cars to slow down. “They create safer roads for cyclists; that’s very important.” On housing policy, Cruz cited his own life experience as a longtime tenant of the Housing Authority. Without such housing, he said, he could never have taken advantage of the educational opportunities Santa Barbara has to offer. He would focus he said on expanding opportunities for low income individuals. He expressed skepticism about City Hall granting developers’ permission to build “70-foot monstrosities” in exchange for a few units of workforce housing. “That’s not work force housing, and that’s not in keeping with Santa Barbara’s historic character.”

Where the budget is concerned, Cruz cited his five years working for H&R block, helping people prepare tax returns. He also cited his long experience working with non-profit social service agencies working in conjunction with private funding sources. “Santa is a very rich and vibrant and giving community,” he said. “We can solve a lot of our problems by fundraising locally.” To that end, he said, “I hope to provide good medicine and an opportunity to learn from our mistakes.”

JUSTIN TEVIS: By far, the youngest candidate in the race, Justin Tevis, 26, is certainly the most old-school when it comes to his brand of conservatism. More libertarian than Republican, Tevis opposes the ever expanding police powers of the state. He parted political company with George W. Bush over the Patriot Act, which gave the federal government new authority to spy on private citizens. Likewise, he opposes what he regards government intrusion into the free market, and proved exceptionally vocal in his denunciations of the proposed the health care reform package at a rally in front of Congress member Lois Capps’ office two months ago. “I like personal responsibility, living free, taking the initiative, being able to compete, and being able to fail,” he said. He opposes government bail-outs of companies deemed “too big to fail,” he said, because, “America has always been about being able to fail and get back up again.”

Tevis was born in Goleta, raised in the Santa Ynez valley, where he played high school football, got straight As, and was never so much as elected hall monitor. A martial artist, Tevis recently won the Grapplers Quest contest for his weight category in Las Vegas for Brazilian Jiu-jitsu. By day, Tevis does market research for Territory Ahead, figuring out what styles and colors of women’s clothes will sell and how much should be ordered.

Tevis said he began thinking about running for office since last October when the fiscal sky really fell on City Hall. But he was catapulted into the race in February, he said, after the City Council voted to give a 2.5 percent pay increase to its general employees union and an additional paid vacation. “Nobody in the private sector is getting a raise. Nobody in the private sector is getting an extra holiday,” he said. In addition, Tevis said too many city workers are making too much, relative to what the private sector pays. “We have 100 people making more than $90,000 a year,” he said. “There’s just a huge disconnect out there between what regular people think and what goes on at City hall.”

Tevis attributes this cognitive gap to the interfering influence wielded by special interests. Early on in the campaign, Tevis was one of the loudest critics of public employee unions and their political contributions. Now, he’s grown almost as vociferous about the contributions of Texas billionaire – and former Santa Barbara resident -Randall Van Wolfswinkel, whose raised more than $250,000 for his slate. Tevis, who was endorsed by local Republicans and by the News-Press, was unhappy Van Wolfswinkel never saw fit to interview him before opting to back other candidates.

Tevis noted that most public employees are covered by existing contracts that can’t be wished away. He aid City Hall needs to get the unions back to the bargaining table to negotiate beneficial reductions in pay and salaries. In addition, he said the city should increase the retirement age of city employees. Tevis faults the police for not taking a more aggressive stand against gangs and graffiti, and suggested too many officers are deployed in revenue generating duties. “There’s graffiti all over the place that goes un-prosecuted,” he said. “But if you’re not wearing your seat belt, they’ll pull you over and charge you $100.” As part of his anti-gang strategy, Tevis said parents should be held accountable for the misdeeds of their children, and that in lieu of community service, juvenile offenders should be forced to participate in sports activities.

Tevis admitted feeling conflicted about Measure B, which would reduce allowable building heights – admittedly a government intrusion into the free market – but supports it, he said, because the initiative “will help protects Santa Barbara a special place.” Opponents of Measure B, he said, do so because they want higher densities to accommodate affordable housing. “That creates lotteries,” he objected, “of who gets in and who doesn’t.” As burly as he is, Tevis said he’s been accosted by aggressive street people and supports tougher laws designed to “clean up downtown.” Businesses have a right to operate without being harassed by the homeless, he said.

Where Tevis’s politics tend to be tough and uncompromising, in person he comes across sweet and congenial. As a candidate, he’s as fiercely competitive as he is as an athlete. “We’re in this to win. Not next time, but now,” he said. “With the city facing a $5 million deficit, the best opportunity is right now.”