Finding New Life on Dead Oil Rigs

Producing and Decommissioned Platforms Support Aquatic Species

When an oil rig is decommissioned, fish see an opportunity for a new home. UCSB biologist, Milton Love, has led a research team conducting and exploring the potential for oil platforms to have a new life after their retirement, or “rigs to reefs.”

The coastal shelf of California is peppered with over 20 oil and gas platforms. The water columns of oil platforms harbor various sorts of rockfishes in the midwater with larger, and often adult, fishes congregating at the bottom. Not all species of fishes are found multiplying around the rigs, but most of the ones that do have commercial and recreational value.

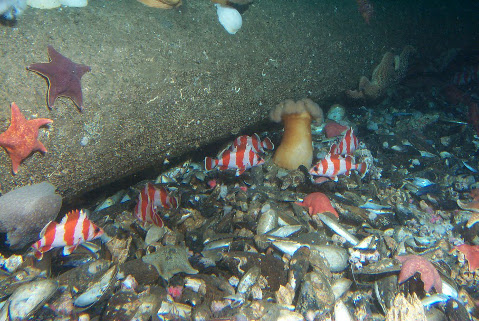

“These are really just large reefs,” Love said. “And they’re filled not only with fishes but millions, hundreds of millions, probably billions of other animals, sea stars, sea anemones, mussels, and barnacles.”

When Love and his associates measured the secondary productivity of the platforms, which consists of the number of fishes on the platforms, their density, and growth rate, they found that the oil rigs were the most productive areas in the world for fish populations.

The platforms may also aid in the rebound of fish population numbers. Take the boccaccio ( Sebastes paucispinis) for instance, which was once one of the most overfished species of fish in the state but began appearing in thousands around the rigs’ thriving ecosystems.

Much of the sentiment toward leaving decommissioned rigs in the water rests on the compromise that they will be dismantled and trimmed to an extent. These heavy industrial facilities have presented challenges regarding environmental impact in both their active drilling and dormant decommissioned states.

“We did a study a few years back that showed that even if you cut them 100 feet below the surface,” Love said. “They would still act as nursery grounds.”

As one might expect, the idea of allowing the presence of these artificial intrusions in the ocean has stirred controversy. The platforms have been cited as visual pollution and an emblem of the environmental movement’s quintessential nemesis, the oil and gas industry. Some believe that going as far praising the structures for their contributions to marine life is not only wrong but rewards the fossil fuel industry for interfering with the coastal marine ecosystem in search of resources.

Biologists are looking at additional quantitative concerns. Questions regarding the leakage and contamination of nearby waters and animals by heavy metals were studied by Dr. Love, who collected fishes around and away from platforms and sent them to a federal lab in Missouri to be tested.

“They couldn’t find a difference in the amount of heavy metals,” he said. “The things you might expect: Mercury, cadmium, barium, lead, the kind of things at industrial facilities — particularly drilling facilities — you might expect to see in higher amounts. There was no difference in any of those elements between control fishes and fishes around platforms.”

Aside from his research on rigs to reefs, Love also works with the Doug McCauley lab on a giant sea bass project. His work attracts a community of collaborators including the United States Geological Survey, Bureau of Offshore Energy Management, and National Fisheries Service.

Love and his associate Mary Nishimoto are currently working on the BON project to develop a Biodiversity Observation Network (BON) in the test bed of the Santa Barbara Channel.