Bobby Isaacson, 1948-2012

Storyteller, Teacher, Rancher, Friend

Bobby was no good at endings.

In the late 1980s when our daughters were still running around in cowboy boots waving fairy wands, Robert Anton Isaacson invented a board game called “Land Grant.” It played like Monopoly, but instead of streets in Atlantic City, the board was a map of Santa Barbara County 150 years ago. Either by purchase or draw (the roles changed somewhat randomly), you got a ranch, and you started buying cattle. There were Chance cards: oil discovered, drought, random calamities, good poker nights. Towns could be built, but since the players were neighbors — guys, like Bobby, who ran cattle, or beekeepers or farmers — putting up towns was a little like going over to the dark side. Either way, you could make a fortune or lose one. But the game never seemed to end. Eventually, I started complaining that we were going to be here until 4 a.m., and we had to be up at 5 a.m. His wife, Sally, had fallen asleep hours ago. The dilemma of how to end flustered Bob.

In Robert Isaacson’s universe, James Joyce’s Ulysses was the greatest book on earth. Bob and I were both English majors at the same time, him at Claremont, me at UCLA, but I had avoided Joyce like the draft. This was because I was uninitiated. You needed to peel Joyce back, and Bobby had done that. Isaacson had descended on Ireland like the weather. He courted Dublin. He married an Irish girl. They named their daughter Katie Rose. He followed Joyce’s trail of troubles through Europe. By the time his daughter was in college, he kept extra copies of Ulysses tucked in a drawer at their house so he could pass them out to Katie’s friends. What one needed to know about Joyce, what Bobby wanted everyone to understand about Ulysses, was that the book was great fun.

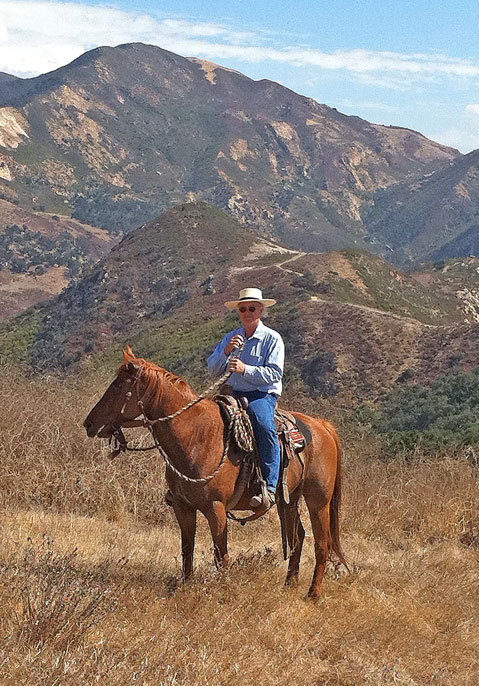

And fun was good. He taught the joy of English literature at Allan Hancock College in Santa Maria for 30 years. Talking was fun, and Bob loved to talk. He was better at it than listening. He wrote poetry about ranching. He didn’t have anywhere near enough hair to compete with Einstein, but under a cowboy hat, the effect was similar. Bobby loved the story of California. He loved cattle work. He loved a big loop with a rawhide reata. And talking about buying an old Las Cruces horse bit was almost as good as owning it.

For years he had driven into Lompoc a couple of evenings a month to Lawrence Dutra’s garage on Seventh and Lemon. Lawrence was teaching a few of the younger guys to braid rawhide. Lawrence had been born off Route 1 in Lompoc just over the hill from the Isaacson ranch, El Chorro. Lawrence had managed the Cojo-Jalama for years but had retired to be the county cattle brand inspector. Everybody had a pair of Lawrence’s reins. Bobby made his own.

We rode a lot back then. I’d gotten into the cattle business partly because of Bobby. The week before I got married, he’d sat me down at the kitchen table and penciled out on three sheets of yellow legal paper a generic kind of profit and loss for the cattle business. Even now a guy can get suntanned from the giddy optimism of those numbers. In fact, the morning fog was a more common weather. It could be so thick you couldn’t see the horse in front of you, and so before we got to the top ridge, we’d hang back below the crest, out of the wind at least, and wait on patient horses: passing time.

Bobby might not have understood everything, but he understood this: The land had to stay. People wouldn’t survive the loss of the wild — not to mention the unhappy fate of everything else living out there in the mist. Eventually the fog would pull back toward Lompoc, and you could see the cattle; you could see the islands in the channel and Figueroa Mountain across the valley. Bob and his brothers, Deming and Bill, put a conservation easement on the El Chorro with the California Rangeland Trust.

One morning on his commute to his day job at Hancock, he drove by Kendall-Jackson’s field off 101 as it was prepping for a vineyard. D8s were bulldozing out huge white oaks. Bobby came over to my house that night enraged about the stupid things people think they can do to land and how the county never seems to know what to do. He wrote a letter to The Santa Barbara Independent. He wrote a lot of letters; he called people. And as a result, back when Apple sold for $14 a share, the county warred for three years about oak trees and finally resolved it all with an oak ordinance, which nobody liked — but the valley white oaks got protected.

Bob’s grandfather registered the Muleshoe brand in 1906. Bobby coauthored a book on the Muleshoe Cattle Company chronicling that earlier Isaacson who, after he dropped out of college in 1905, took a train west along the Canadian border to Montana, bought horses, and set out toward Mexico to find the perfect ranch. “Fear drought and think big” was how Bob summed up his grandfather’s 22-year Arizona saga.

Bob had had prostate cancer for seven years, but he had lived with it and the attendant therapies with his usual good humor. I had visited him at his house in the week before he died. As night fell, he grew tired. “I have no desire … ” he said. I thought he was going to say more, but he didn’t — as if suddenly surprised — as if some greater drought had come, and the reservoir was almost dry.

But Bobby was no good at endings. He was one of those guys who just liked the game. Someone else could figure out how to end it. There would always be some Chance card to be picked; some drought to ride out or to lay you in the dust; some story to retell around a flatbed after branding; some heifer that Sally would push him out of bed to check on some cold and rainy night; some other street in Dublin.