Question: ‘What is the story behind this drawing of Santa Barbara?

-Dan Patterson

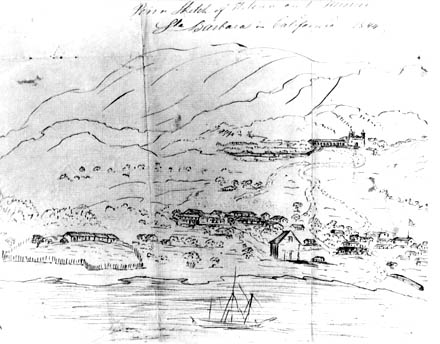

This pen and ink drawing of Santa Barbara, dated 1844, was executed by a Swede traveling through California in the years 1842-43, G. M. Waseurtz af Sandels. Sandels kept a journal during his travels, with comments on the places he visited and, periodically, with sketches. His journal, thought lost until published by the Society of California Pioneers in 1926, offers a fascinating portrait of California toward the end of Mexican rule.

Biographical details on Sandels are few. He appears to have been well-educated, for he referred to himself as one of the “King’s Orphans,” as in, he had attended a governmental educational institution in his native Sweden. In an 1843 letter to Mariano Vallejo, Sandels referred to himself as “physician, mining expert, naturalist.” He lived for a time in Brazil, won and then lost a fortune while mining in Mexico, and was intrigued by the possibility of gold in northern California years before the Gold Rush era.

Late in the 1840s, Sandels, wracked by tuberculosis, showed up in New Orleans, where he made the acquaintance of local journalist T.B. Thorpe. Sandels handed his travel journal over to Thorpe, instructing him to make sure it got back to Sweden. Thorpe kept the manuscript, however, and its whereabouts remained a mystery, although portions of it were published throughout the years. The complete work only came to light when it came into the possession of the Society of California Pioneers.

The journal chronicles the author’s trip from Acapulco to Monterey, beginning in September 1842, and his subsequent journeys up and down California into the next year. The exact chronology of his travels is unclear, but he seems to have visited Santa Barbara in April 1843, according to another of his letters to Vallejo. In general, he seemed favorably impressed with the town, remarking, “The town is tolerably well-built, but not very regular. You can’t but remark the difference between the towns built up during the monarchical government of Spain and those who have grown up during the republic. The former are remarkable for regularity and straight streets.” It should be remembered that Santa Barbara’s grid pattern of streets was not laid out until the early 1850s.

Sandels met a number of town luminaries, including Daniel Hill, Jose de la Guerra, Thomas Robbins, and Father Narciso Dur¡n of the Old Mission. Sandels even practiced a little medicine, traveling over to Mission Santa Ines to treat a padre there for asthma and heart trouble. He was successful enough that the padre could perform Easter week services. He also visited the “Naptha Springs,” probably the asphaltum springs once located where UCSB is today. He noted how the naptha was often used to tar roofs, which resulted in a disagreeable odor and melting problems in hot weather. Sandels also commented on the oil floating on the Channel waters, a condition that, of course, persists today.

Sandels was quite impressed with the fine condition of Mission Santa Barbara’s buildings, having seen a number of other missions in California in almost total ruin. He commented unfavorably, however, on the lack of a school in Santa Barbara: “The great number of children in want of education is prominent.” He also felt the town needed a well-trained medical man; Sandels spent a good part of his stay in Santa Barbara attending to the ills of its citizens.

His Santa Barbara sketch shows the adobe at Burton’s Mound at left (razed to make way for the Potter Hotel), the cattle hide storehouse near the beach in the middle, and the presidio, its flag flying, on the right. The mission may be seen easily in the right background.

Although not a polished work, Sandel’s drawing still wonderfully documents Santa Barbara shortly before its transition from Mexican pueblo to American town.