Davy Brown Camp

Car Camping with Former Strangers

Two Hikes: Willow Spring Trail moderate day hike; Potrero Canyon 8-mile hike on day two

Mileage: 5.0 mile moderate round-trip on Willow Trail (spur); 8.6 miles round-trip to Potrero Canyon Wind Caves (ascends the Hurricane Deck formation)

Suggested Time: 2 days/1 night; very pleasant for hardy kids older than 6 or 7

Map: B. Conant’s San Rafael Wilderness Trail Map Guide (2009)

While dedicated backpackers savor the sacred three-day weekends with that alluring 3/2 template mentioned in the last column, aggressive day hikers will love the following 2/1 backcountry template featuring the Willow Spring and Potrero Canyon day hikes.

The following narrative describes a pair of dayhikes sandwiched around one night sleeping in my truck at Davy Brown Camp. Committing to a 2/1 like this will stir your blood, inspire your wanderlust, and reawaken your childlike sense of play.

Near the top of my hierarchy of backcountry saints stands bold Davy Brown, the ex-slaver who died in 1898 in nearby Guadalupe. This backcountry minimalist’s name stands up there with that of Hiram Preserved Wheat and the mysterious Joaquin Murrieta, the Mexican Robin Hood. The perennial creek named after old man Davy Brown flows strong and pure in the mostly arid National Forest.

The USFS camp here has also been named after Davy Brown, and this sweet creekside bench is a fairly ascetic site for car camping. The government simply provides an iron fire ring, a wooden table, a very handy BBQ box on four-foot stand, with adjustable grill, for each of the 13 car camp locations; and, just lately, two lovely new bathrooms (still pit toilets, however). There is no trash pickup or piped water (bring water).

I

After driving the 47 miles to Davy Brown Camp from Santa Barbara and setting up my Spartan gear, my friend Chris and I begin hiking down the creek to the bottom end of the camp, crossing the stream (slippery here), and halting momentarily at the green metal gate. After entering (be sure to refasten the swinging gate), the beautiful path turns left (south), and you begin ascending up the verdant canyon. In about one mile you find trail signs (no names): A left takes you up gorgeous Fir Canyon ending at Figueroa Mountain Road, but the steep uphill right (west) places you on the radiant Willow Spring Trail.

While this first day’s mileage adds up to just a five-mile trek, the initial half is quite steep since you are actually ascending some of the back side of well-known Figueroa Mountain (4500 ft.) and the Pino Alto. Wielding the twin Leki hiking poles helped, but I had to slow down greatly and accept that I wouldn’t get all the way to the base of Figueroa Peak or over to where the trail hits the Catway Road.

As other writers have noted, the spectacular views back — northeast toward the Hurricane Deck formation — render this short but intense day hike even more worthwhile. These vistas stand tall and magnificent on your left side as you slowly hike back, once you’ve had enough strenuous exertion — you also see mysterious climbing rocks beckoning you on. Chris challenged me to cross over there on the way back and search for pictographs, but I was exhausted and we didn’t have rope, gloves, or long pants (fierce and thorny chaparral all around).

The steep 2.5 mile descent down to Davy Brown and our table and campsite was easy, and once there my friend and I turned on the twin-burner grill to heat the vegetable stew brought from home. The blessings of car camping lie in having so much more stuff — like nutritious food and books — than when backpacking into the San Raf. Later, I tuned up my trail guitar, and we sang some good old songs, old-timey and neo-Carter Family three-chord masterpieces from the American songbook.

Achieving solitude by getting away from most people is the main reason most of these columns showcase either a strenuous day hike or overnight backpack. Rarely do I describe the interludes between hikes or the evening camped by a vehicle — in this case my ’00 Ranger truck hunched beneath towering sycamores and oaks. However, at dusk, Chris and I were serenading away beside the tumbling creek (after plucking a couple of songs, I yielded the trail guitar to him, which made the music much better). And as we were singing Springsteen’s “Patrolman” ballad, a group of men from a nearby site began calling out, “Fantastic … come over and join us!”

II

When the three guys from Lompoc loudly applauded our lusty minstrelsy and hollered “That’s awesome!” we knew we had a gig.

The laughter-filled social interlude reminded me of psychologist Alison Gopnik’s comment that children are not “defective adults.” Rather, they are different forms of Homo sapiens: adults work, but babies and children get to play (The Philosophical Baby, 2009). All adults were once babies, of course, and when we big people find an interregnum between our duties, we begin to play and our sense of wonder grows.

Led by a cool guy I called Big Mike, the three men had carefully unloaded mounds of supplies from their three half-ton pickups, ranging from a half-cord of split oak, to several massive ice chests, to clean tables, plates and dinnerware, and a tall black smoker. It was early evening, so their legal fire in the iron ring raised yellow and orange fingers into the darkening backcountry sky. No one was staying at the other 11 car-camp sites. Steve and Steve constantly thrust terrific food and an amazing assortment of quality beer from the ice chests upon us.

As Chris and I wailed away on our best backcountry set of 10 songs, the camaraderie and brotherly feelings were bubbling. And when the leftie in me tried to speak, maybe to ask about their ideas on aerial assassinations of American citizens abroad, a sharp kick from Chris made me realize I should shut that up and get back to playing. I could feel the primordial creativity being released by that fire as men from vastly different towns enjoyed talking and getting to know one another. A few hours of chanting and chatting, mindfully avoiding strife, left the mind and spirit more free to imagine new and different thoughts and ideas.

Gopnik claims that the greatest human capacity is to see different futures and make changes to achieve some of them, which takes childhood play and adult work.

III

After falling asleep in the truck bed, well-oiled by the soporific effects of a few generous pulls on big Mike’s bottle of Hornitos tequila (¡anejo!), I am up at 4 a.m. boiling water for coffee. Bundled up at the wooden table next to the chanting brook, I can see my friend’s tent nearby and realize he needs to be awakened.

These two day hikes are ideal, complementary bookends for car camping. From Willow Spring Trail we looked over to the Hurricane Deck, which we’re now headed toward (though not all the way to), and now, on the second day’s Potrero Canyon hike, we will have wonderful views to the back of Figueroa Mountain and the Willow Spring Trail itself.

By 7 a.m. we’re setting off on the much more challenging 8.6 mile Potrero Canyon Hike in search of what were once termed “Indian Caves” (sometimes considered a pejorative), which are shallow rock shelters I call natural wind caves.

We drive one mile from Davy Brown Campground down to the Manzana Creek, just shy of Nira Camp. Our first, easy hiking segment began with our crossing Davy Brown Creek where it dumps into the much larger Manzana. This crossing is actually a little tricky and slippery at 7:15 a.m.; exercise great care. Here you see the handsome wooden trail sign for Manzana Trail, Potrero Camp, Coldwater Camp, and Manzana Schoolhouse (we will not go to the latter two).

After getting over Davy Brown Creek, we amble along the well-trodden trail to reach Potrero (Canyon) Camp in just over a mile. Chris and I notice it will be a hot day, and that’s amazing since it’s late February. At Potrero we ford the larger Manzana Creek and ascend steadily about 1,600 feet, a demanding trudge on a rocky trail through hard chaparral.

As we’re climbing toward the apex of the fabled Hurricane Deck formation (3,300 feet high) and looking back to admire Figueroa Mountain and Zaca Peak, we also observe the ivory peak that Ray Ford has called Castle Crags on his old Red Map No. 1. After about two hours we approach some isolated and beautiful “whale rocks” of white sandstone, signaling that we are close to the curious wind caves.

Above us looms Hurricane Deck itself — an arid, rocky, and completely quiet place teeming with hidden life.

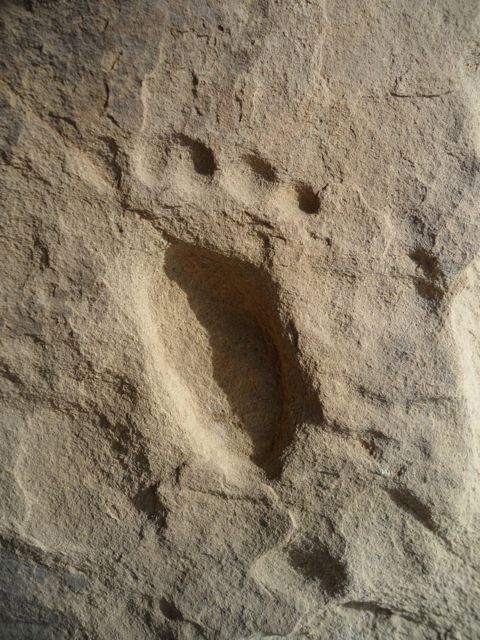

We drop down a bit from the whale rocks and find ourselves in a slanting potrero glistening green from the recent, if scanty, winter rains. On the right is an upthrust ridge of rocks and the wind caves, easily discernable and worth exploring. If one looks very carefully, there are a few faint traces of red Chumash pictographs, but time and wind and careless fire-makers have left these barely visible. Though they are heavily damaged, treat them with respect and sketch some if you can (red triangles predominate if you can make them out).

From here, one can ascend another half hour and reach the apex of the Deck, but we chose the more difficult direction east, a trail-less bushwhack into a number of arroyos and small canyons. This section is quite heavy going, and while a few animal trails help guide the way, we are very glad we wore long pants and heavy long-sleeved shirts, and even then I get pretty scratched up. I do not recommend undertaking this section alone.

We were in search of the fabled bear-paw petroglyph, hidden within one of the several whale rock white sandstone formations in this area, all of which are very difficult to access. Petroglyphs are Native American rock art designs actually cut into the rock, as opposed to pictographs, which involve painting on the rock.

I’ve made many searches for petroglyphs in California and Oregon, and they are much more rare than the showier pictographs. There are some easy-to-find petroglyphs outside of Bishop at Fish Slough, if you are driving to Mammoth Lakes. There are many also beautiful designs at the well-known but very remote Petroglyph Lake site in eastern Oregon.

After some hours of searching and bushwhacking — and I will not give this location away — we manage to locate one of three bear-paw petroglyphs inside this cave. (The views in the accompanying photos are from inside the cave.) It is very laborious and also very exciting to find this site again. Last year, the USFS had an iron box on a metal pole near the rock art site, but by February 2013 it had been removed. Probably the removal was a good idea, since these sacred places are completely unprotected.

After seven hours on the trail and scrambling through many rock shelters, we arrived back at the vehicle parked near Nira. A quick washup in the creek, and then the pleasant 90-minute drive home via Highway 154 to Santa Barbara’s Westside.

Gopnik demonstrates the “usefulness of uselessness” in the very long human childhood — such as imaginary companions (Chumashan spirit-helpers?) and other “counterfactual thinking” — for imagining new human futures. Grabbing your children and hightailing it to Davy Brown Camp can stimulate creativity and grant the opportunity for deep rest. You may not get any work accomplished, but your child’s prefrontal cortex will expand exponentially as s/he plays outside.

Ten backcountry tunes Chris and I sang at Davy Brown for the Lompoc boys: “Orphan Girl” (Gillian Welch), “Take ‘Em Away” (John Prine), “Patrolman (Bruce Springsteen), “Battle Cry of Freedom” (G.F. Root, 1862), “Paradise” (Prine), “By the Mark” (Welch), “Dark As A Dungeon” (Merle Travis), “Angel from Montgomery” (Prine), “Leavin’ Louisiana” (Rodney Crowell/Donivan Cowart), “Long Black Veil” (Johnny Cash)