There’s much concern regarding the decline in bird populations, but are there any birds that are actually doing well locally? There certainly are, but they’re often not the birds that make people happy. The much-maligned American crow has seen a big spike in numbers over the last few years. Turkey vultures are also doing very nicely. Then there are species formerly found on the fringes of the suburbs that have now adapted to living with people. The Cooper’s hawk has become a reasonably common nester along the South Coast, where it finds easy pickings at backyard feeders.

I’ve lived on the Westside for nearly 30 years, and there are birds that I rarely saw in my neighborhood when I moved in that I see or hear daily now. These include the white-breasted nuthatch, dark-eyed junco, band-tailed pigeon, and Bewick’s wren.

Other birds have seen a noticeable increase because measures have been taken to protect them. Brown pelicans have rebounded since the banning of DDT, and peregrine falcons are another success story, partly because of reintroduction programs.

The change in climate is having a profoundly negative effect on birds and other life, but there are some instances where the warming earth and oceans have helped bring more southerly species into our area. It wasn’t so long ago that I remember chasing my first county sighting of black skimmer and yellow-crowned night heron; both are now a regular part of our fauna. Cocos and blue-footed boobies have nested on Santa Barbara Island, and three other species of this spectacular tropical family are now regular visitors. Allen’s hummingbirds, once rare in winter, are so abundant they sometimes outnumber Anna’s hummers.

There are also birds that have benefited because of our presence. Hooded orioles, which sew their hanging nests on the underside of palm fronds, have expanded their range greatly since the widespread planting of ornamental palms. The familiar house finch does particularly well around human-created habitats.

One bird that was almost certainly never found in our area but, for better or worse, is now thriving, is the brown-headed cowbird. The cowbird was originally a bird of the Great Plains, where it followed bison herds and fed on the insects and seeds that were stirred up by their hooves. Because of their nomadic existence, they developed an interesting breeding strategy. Like the European cuckoo, the cowbird is a brood parasite. They don’t build their own nests, but the female watches quietly while other species construct their own, then while they are away, she lays her egg in the strangers’ nest and leaves for the hosts to raise her young as their own. This was a good strategy for a bird that was always on the move.

Cowbirds are known to parasitize 220 species of birds, but most individuals specialize in targeting one or two kinds. The female can lay as many as three dozen eggs in a single summer. A few birds recognize that the egg is different from those in her own clutch. The yellow warbler is an example. They are too small to eject the cowbird egg, so they will build a new nest on top of the imposter’s egg. Other birds will puncture the egg, and some will toss it from the nest. Most birds, however, don’t recognize the alien egg and raise the young cowbird without seeming to complain.

The cowbird egg hatches faster than the host’s, and therefore the cowbird chick is fed first, grows rapidly, and demands the lion’s share of the food. They will smother the other chicks, or will even push them out of the nest.

You might have guessed the reason that the cowbird rapidly spread away from the Great Plains. When Europeans arrived, they not only chopped down the forests, but brought cattle and horses, a reasonable substitute for bison when the great herds disappeared. The fragmentation of the great eastern forests allowed the cowbird to spread all the way to the east coast, and ranching helped them spread throughout the west. Cowbirds now parasitize a far greater variety of songbirds than they did when their range was restricted, and they are implicated in the rapid decline in a number of vulnerable species.

The male cowbird is black with a brown head, while the female is a pale brown, lightest on the underparts. They are smaller than other blackbirds. If you see a flock feeding on the ground together, a good field mark is that they hold their tails skyward. So where can you see a brown-headed cowbird? Take a field trip to Costco and hang around the food court. There you will invariably find a flock of cowbirds, mingling with the larger Brewer’s blackbirds, scarfing down any unattended food.

Hugh Ranson is a member of Santa Barbara Audubon Society, a nonprofit organization that protects area birdlife and habitat and connects people with birds through education, conservation, and science. For more information, see SantaBarbaraAudubon.org.

Premier Events

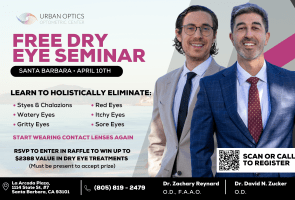

Thu, Apr 10 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Free Dry Eye Seminar w/ Dr. Zucker & Dr. Reynard

Fri, May 23 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Songbird: The Singular Tribute to Barbra Streisand

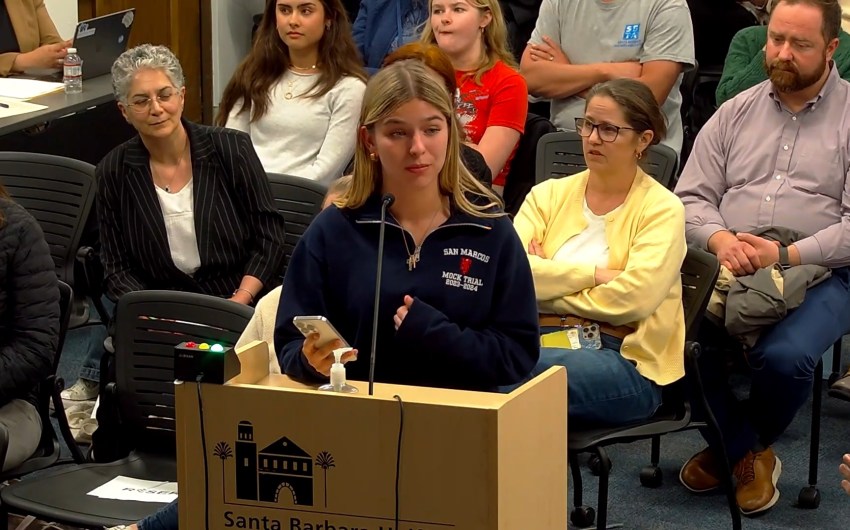

Mon, Mar 24 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Hope, Power, Action: Rising Above the Muck to Lead

Fri, Mar 28 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

The Happiness Habit (2 for 1)

Sat, Apr 05 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Planned Parenthood’s Birds and Bees Bash

Sat, Apr 05 7:00 PM

Solvang

Concert: Ozomatli

Fri, Apr 11 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

The Happiness Habit (2 for 1)

Sat, Apr 12 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Titanic Anniversary Event

Fri, Apr 18 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

The Happiness Habit (2 for 1)

Mon, Jun 16 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.