[Update: Wed., Feb. 19, 2025, 10:30am] After being issued a second cease-and-desist order by the California Coastal Commission on February 18, Sable Offshore hit back with a same-day lawsuit against the state agency in Santa Barbara Superior Court.

The complaint alleges that the Coastal Commission’s issuance of cease-and-desist orders is “procedurally improper,” and that the state cannot legally stop Sable from completing “repair and maintenance” activities on the oil pipeline. Sable cites a February 12 letter from Santa Barbara County energy planner Errin Briggs, stating that Sable’s work on the pipelines is allowed under permits issued in 1988 to the pipeline’s previous owner. The Coastal Commission, on the other hand, contends that Sable’s work classifies as development rather than routine maintenance, and requires new coastal development permits to complete.

Sable has asked for a declaration from the Coastal Commission that their actions were unlawful. The oil company is also seeking an injunction that bars the Coastal Commission from issuing any additional violation notices or cease-and-desist orders for repair work moving forward. Sable will pursue monetary damages for the violation of their property and attorneys’ fees.

Joshua Smith, a spokesperson from the California Coastal Commission, declined to comment on the pending litigation.

[Original Story] Kate Huckelbridge, executive director for the California Coastal Commission, issued Sable Offshore a cease-and-desist order for repair work Sable work crews had been doing on Sable’s two oil pipelines since the first cease-and-desist order issued last November by the Coastal Commission expired last week. The order also mentions the serious possibility of civil fines — some as high as $11,250 per violation per day and others as low as $500.

At the heart of the issue is a profound legal dispute between Sable — which is engaged in an effort to restart the oil and gas facility it purchased two years ago from ExxonMobil — and the Coastal Commission whether the work in question qualifies as repair and maintenance or new development. If it’s the former, Sable — a startup oil company formed in 2020 — would not need the Coastal Development Permit the Coastal Commission insists it does. If, however, the work — which has included the installation of new automatic shutoff valves and considerable repair work done on corroded pockets of the pipelines — is deemed “new” development, then such a permit would be required.

The Coastal Commission and Sable have been at loggerheads over this issue since late last September, when the commission first began peppering the oil company with notices of violation for work being done on the pipeline in coastal zones. While many meetings took place and multiple emails were exchanged, no agreement was ever reached.

Huckelbridge sent out her first cease-and-desist letter last November. In it, she all but accused Sable of providing false assurances that the work had been stopped when in fact it had not been. With the second cease-and-desist order, many of the same issues remain, but newer ones make it even more complex.

For example, the County of Santa Barbara’s chief energy planner, Errin Briggs, issued a letter last week notifying Sable that it was his belief that the pipeline’s original permit conditions — approved in 1988 — allowed Sable to do the work it was doing.

Making this more complicated still, the county has also asserted that it has no jurisdiction over any underground work done on the pipeline pursuant to a legal settlement it entered into with the pipeline’s original owner in 1988. That settlement stemmed from a bitter legal dispute between the county and the pipeline’s first owner over the county’s jurisdiction; the county lost that fight.

Privately, Coastal Commissioners and staff have expressed frustration with the county for not asserting more land-use authority if only for the remedial work Sable has been in a hurry to do along multiple creek crossings located within the coastal zone.

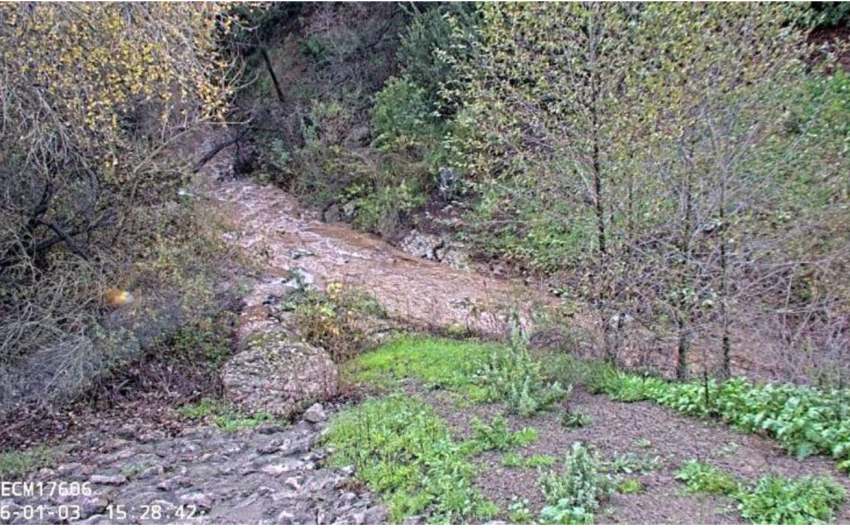

Based on the language included in the second cease-and-desist order, it’s not clear what damage has, in fact, been inflicted on the environment by Sable’s work as opposed to what damage might be inflicted. According to the letter, the work Sable’s been doing “would be likely to contribute to environmental impacts that could have been avoided, including the destabilization of rain-soaked hillsides and habitat area, discharge of mud and debris into watercourses and wetlands, disturbances to nesting birds that could lead to nest and habitat abandonment, and declines in breeding success.”

Further, the history of this site has made it clear that the utmost caution and safety must be taken to avoid catastrophic damage to coastal resources such as those seen after the 2015 pipeline failure and resulting Refugio Oil Spill.

The actual work in question, according to the order, involved a stretch of waterfront area running 750 linear feet to create support piers along 14 pipeline spans of between 14 and 71 feet. Underlying the technical and legal issues involved is a concern by the Coastal Commission that this work is all part of a larger effort to restart Exxon’s oil and gas plant and pipeline near Refugio.

Although the plant was shut down through no fault of Exxon, the Coastal Commission has insisted Sable needs to submit an application for a new Coastal Development Permit because the work involved entails new development. Exxon’s plant has been shut down 10 years because of that pipeline spill, which occurred under the criminally negligent watch of then-operator Plains All-American Pipeline. Initially, Plains — and later Exxon itself — proposed installing a brand-new pipeline to deal with the serious corrosion problems of the existing one. Given what a regulatory minefield that was, Exxon — and later Sable — opted to use the existing pipeline, which Sable has stated could be made “good as new.”

This has subsequently become the focus of an intense legal and political battle, precious little of which falls within the jurisdictional discretion of the county Board of Supervisors. The only jurisdiction exerted by the supervisors is whether to allow Exxon to transfer its title and permit to Sable. That question — otherwise almost always a ministerial formality — goes before the supervisors for approval next Tuesday, February 25.

Environmental opponents of the project — and the transfer — are making the case that the two cease-and-desist orders issued by the Coastal Commission demonstrate that Sable is not operating in good faith. But with the county energy planners siding with Sable, that argument will carry less weight.