Century-Old Seaweeds

Discovered in

Carpinteria Attic

Rare Species Collection Shows Ocean

Changes After Industrialization and Plastics

By Callie Fausey | February 13, 2025

It’s not something one admires every day. I mean, even its name elicits a kind of regurgitative response: seaweed. Yes, for most of us, when we feel the slimy, smelly, bug-covered algae beneath our feet as we traverse the beach, we have one thought: “Ew.”

But seaweed has a story to tell, with an unexpected beauty etched into each tendril nurtured by sunlight and ocean currents.

Carpinteria resident Laura Sanchez and her family did their best to preserve a chapter of that story, dating back more than 100 years. Sanchez’s great-great-great grandmother, Juliette Walker Fish, collected and archived seaweed samples from Carpinteria shores in a scrapbook, etched in gorgeous silver lettering with the words, “Moss Album.” Each sample looks like intricate lace sewn onto the page.

The collection gathered dust on a shelf in Sanchez’s grandmother’s attic for decades. However, in October 2024, the family decided to donate their age-old heirloom to UC Santa Barbara for scientific research, learning that it is one of the earliest documented collections in California.

Juliette was an amateur botanist, whether she knew it or not.

“I like picturing Juliette walking along what is now Carpinteria State Beach, gathering specimens,” Sanchez said.

“As a little girl, I remember looking at it with my mom and marveling at the way each specimen has been arranged to appear as if its tendrils are flowing with the waves underwater.”

Great-Great-Great Grandmother

Our story begins with Juliette, who, at 16 years old, traveled west from Iowa to Carpinteria by covered wagon in 1862. The American Civil War had just begun, and people were settling in California after pursuing promises of gold.

Juliette and her fellow pioneers’ memoirs recount this trip and all the meat, potatoes (a luxury), Native American encounters, thunderstorms, trading, fishing, hunting, donkey stealing, fighting, stampeding, ferry tripping, and other drama that accompanied it.

“The stillness that was broken only by the shrill cry of Indians or their songs of victory, the growling of the bear and the sharp bark of the coyote is now pierced by the engine’s whistle and every sound familiar to civilized man,” Juliette told her grandson in 1924, recounting her journey crossing the plains.

The account, preserved in the Santa Barbara Historical Museum, was actually pretty on point with what you’d see in the video game The Oregon Trail — minus the dysentery. I highly recommend reading it if you have the time.

Once settled in Carpinteria, Juliette began her hobby of collecting seaweed along the shore of what is now the Carpinteria State Beach. Her family owned all that property until it was acquired by the state in the 1930s.

Juliette “floated” these specimens in a scrapbook, known as an “herbarium” — a collection of dried plants. Gathering plants of all kinds, such as wildflowers, to press and preserve in an herbarium was a popular Victorian-era hobby, especially for young women. It’s not uncommon now for their descendants to uncover these aging scrapbooks in their attic.

“Each page was so lovingly put together and arranged,” Sanchez said about Juliette’s herbarium. “It’s not just picking up seaweed and slapping it onto paper,” she laughed. “It’s this really painstaking process, floating the seaweed on top of paper and then with a toothpick, fanning out each of the feathery tendrils, making it look like it’s still underwater. It’d take hours, and Juliette had all sorts of different species arranged together in these compositions.”

Collecting these algae specimens — sometimes called “seaweeding” — was one way for Western women of the late 1800s to participate in botanical research, amid a budding recognition of female scientists. Juliette’s work was similar to that of other California women from well-to-do families — one of the most well-known was JM Weeks, who has a red algae named after her.

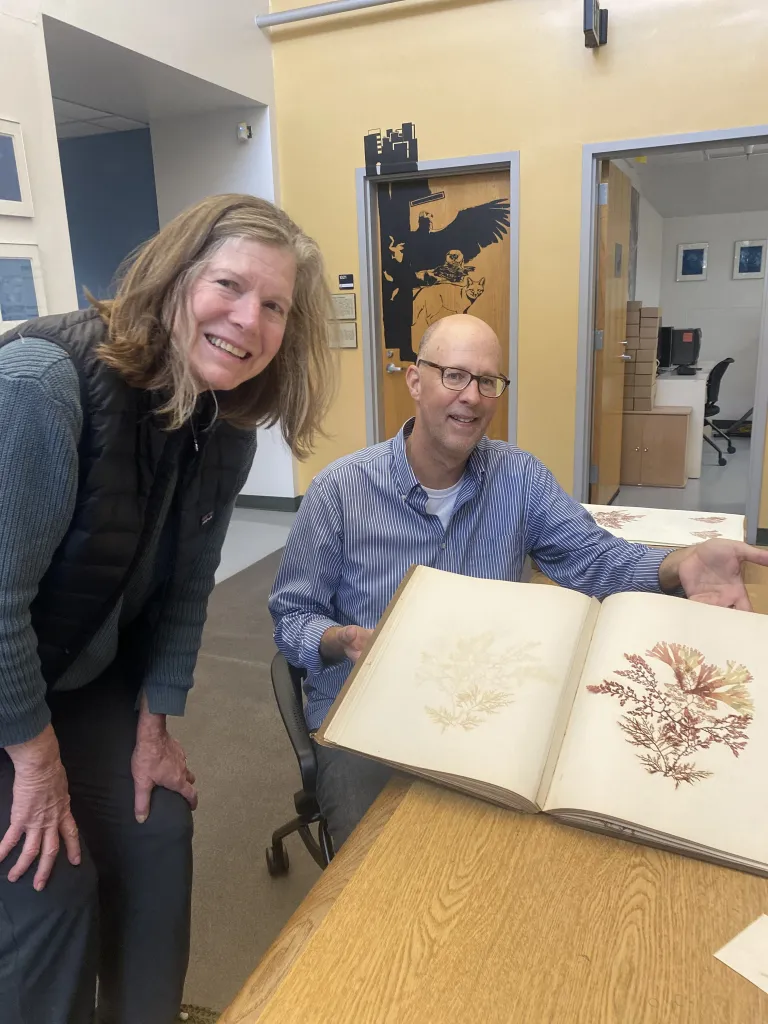

[Click to enlarge] Credit: Ingrid Bostrom

Pressing History

Sanchez first became aware of the importance of her family heirloom when she met Dr. Larry Liddle a few years ago at a fundraiser for Santa Barbara Channelkeeper, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting the Santa Barbara Channel and its watersheds.

Sanchez, the Channelkeeper’s communications director, was intrigued to discover that Liddle, a retired professor who specialized in the study of algae, had a personal collection of herbariums with seaweed he had gathered over the years, similar to the one gathering dust in her grandmother’s attic.

Sanchez told him about this strange collection of her great-great-great grandmother. “I said, ‘Who collects seaweed, and what do you do with it?’ ” she recalled. “And he said, ‘Oh my gosh. I’d love to see it.’ ”

Liddle, now 89 and living in Montecito, said that as a seasoned professional, he admires the work of citizen scientists. “In this field, it’s fascinating how amateurs often make very, very significant contributions,” he told me over the phone. “Especially in the case of a seaweed collection — one that’s so old — it could contain species that no longer exist.”

He explained that such a collection isn’t valuable just because of its age, but also because it can tell how much the environment has changed, particularly in recent decades.

Sanchez’s ancestor’s samples provide a snapshot of the ocean before industrialization, motorized cars, climate change, and plastic pollution began to take their toll. The ancient specimens could provide insight into the genetics of algae and the evolution of certain species, and could give a glimpse into how the ocean is affected by these modern-day influences.

Official documentation about ocean conditions only began about 80 years ago, which can make these old samples a potential scientific gold mine. Others dating from around the same time period have given scientists insight into cycles of upwelling currents and the collapse of fisheries in California, as reported by The Guardian in 2020.

Liddle invited Sanchez to bring the samples to Casa Dorinda, his retirement community in Montecito, where his own work was displayed in an art gallery. There, they examined her family’s oceanic artifacts, attempting to identify certain species and even rehydrating some of the samples.

“They bounced back to life,” Sanchez smiled, “becoming just as slimy and kelpy as the seaweed you’d find at the beach today — within seconds. And each sample tells a story, from tiny reproductive nodes to even little organisms that hitched a ride on the algae.”

Later, Liddle visited the home of Sanchez’s grandmother, Betty Brown, where Juliette’s herbarium was stored. That day, under the careful eyes of her grandmother and her mother, Mary Louise Sanchez, Liddle and Sanchez worked to better preserve the specimens, many of which were loose and falling out of the book.

Liddle encouraged the family to contact UCSB to determine whether the collection had scientific value. After some deliberation, the family decided to donate the heirloom to the school’s Cheadle Center for Biodiversity and Ecological Restoration.

Liddle’s own career in studying algae began at UCSB, after earning his master’s degree at the University of Chicago. He was excited to study the then-relatively unexplored underwater field. Seaweeds, he noted, are some of the oldest multicellular organisms on Earth.

“I asked my professor, ‘Where would be a good place to study algae?’ And he said, ‘UCSB,’ ” Liddle chuckled, adding, “It was the only place I applied to. I don’t know what I would’ve done if they had said no.”

“When I started studying, we would collect seaweed and often find species that weren’t on any lists — things that were relatively new,” he remarked. “The field has grown so much since then.”

[Click to enlarge] Juliette collected hundreds of samples over time, including multiple species, some of which may now be extinct. | Credit: Courtesy

Valuable Specimens

UCSB’s Cheadle Center contains two million specimens — from plants to animals to bugs to eggs to other dead stuff. To Sanchez, it looked like “Disneyland for a naturalist.” The plant collections are stored in a room lined with white storage cases, filled with 150,000 delicately preserved specimens. The room smells of tea, eucalyptus, and the ocean.

Juliette’s samples were photographed and digitally catalogued, and now scientists from around the world can access the collection for their research.

“And it just astounded me that this exists in our backyard,” Sanchez beamed. “The Cheadle Center is such a treasure trove.”

The center is dedicated to restoration and is a de-facto natural history museum. Their collections are “time capsules,” in the words of Dr. Gregory Wahlert, the Shirley Tucker Curator of Biodiversity Collections and Botanical Research at UCSB (a k a resident plant nerd).

“Given the fact that we’re a marine institution here, I really wanted to have a very well-curated, well-represented seaweed collection, so that potentially, the marine biologists here — or anyone, really, with an internet connection — can look at these specimens,” he said. “So, after UC Berkeley, we have the second-largest collection of seaweeds, at least of digitized collections, in the state.”

But the center is stretched extremely thin, and the act of collecting and cataloguing plant specimens is not as valued as it once was. Wahlert had a sad look in his eyes when he described how Duke University decided last year to ditch its centuries-old herbarium and, thus, kill the program.

Collecting specimens and understanding species, how they change over time, and the history involved, is

something that only a natural history museum can do.

“Where else are we going to find a poppy from 1910 and compare it to a poppy today?” he mused.

Herbariums offer an important look into the past to understand the present. For example, Wahlert mentioned that climate change is causing plants to bloom earlier and earlier in the spring, which can mess up plant-pollinator relationships and, at worst, entire ecosystems.

“With samples, specimens, data, you can look at these things and understand important reactions,” he said.

You can infer what a beetle ate 100 years ago, or study gunk from the wings of pigeons alive during the industrial revolution, or find seeds in now-extinct plant specimens and bring them back from the abyss.

Wahlert said that he wished the center had a different name, such as “The Natural History Museum of UCSB” to attract more attention. It’s one of three natural history museums in the region, alongside the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History and the Botanic Garden.

While they don’t usually see people physically coming through their doors to study the collections, they have seven databases all available online so that their specimens are used by around 100 to 200 peer-reviewed papers every year.

“That’s a very important justification for continuing to do what we’re doing, and for expanding and continuing to digitize our collections,” Wahlert said, including Juliette’s samples, which are some of the oldest seaweeds ever collected in California.

“It makes me happy to see Juliette’s adventurous life and work appreciated and honored,” said Sanchez’s mother, Mary Louise.

“She came west in a covered wagon, settled in Carpinteria, and was infinitely curious about the natural world. Our family’s hope is that the seaweed that our great-grandmother gathered may provide inspiration and scientific insights that benefit generations to come.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.