As more Californians have come down with bird flu — 33 people have caught it from dairy cows and one case is of unknown cause — state labs have increased the testing at dairy farms to such a degree that workers analyzing those tests at UC Davis raised the alarm over understaffing at their veterinary lab. To allow the state to add staff and flexibility in contracting and other rules, Governor Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency on Wednesday in response to Avian Influenza A.

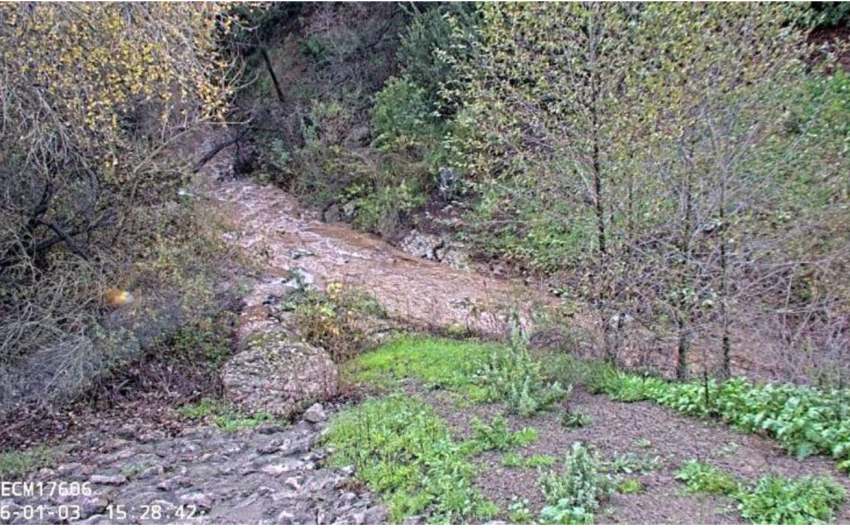

California’s is the largest testing and monitoring of dairies among the 17 states that have positively identified avian flu virus, or H5N1, in their dairy herds. The first lab to detect the virus in raw, unpasteurized milk sold on grocery shelves, however, was in Santa Clara County — at a well-funded public health lab in Silicon Valley — which prompted the state to double its testing at that dairy. Despite all precautions, after the November 24 recall of raw milk from Raw Farm, a second voluntary recall went out three days later, and by December 2, all Raw Farm products were under quarantine.

Public health officials have long regarded raw milk as potentially dangerous as it does not go through pasteurization that kills bacteria and viruses. Raw milk can contain germs that range from tuberculosis to E. coli from cow poop, but proponents believe it retains more healthful minerals and vitamins than the variety heated during pasteurization.

After the recalled raw milk was first pulled from the shelves of a number of Santa Barbara grocery stores, Santa Barbara health official Dr. Henning Ansorg explained that it was highly unlikely for a person to become infected with H5N1 by simply drinking raw milk. If it contained the virus, it’d have to land in your eye or be aspirated deep into your lungs to reach receptors that H5N1 could attach to. This was theoretical, he added, and raw milk remained on the “not advisable” drinks list for the other serious illnesses it can cause.

In a press release this Thursday in response to the state of emergency declaration, Ansorg stated, “The risk to the general public remains low. There have not been any human cases of bird flu in Santa Barbara County at this time and we are closely monitoring the situation.” He added, “Out of an abundance of caution, we are asking residents to consume only pasteurized dairy products and to take additional precautions if working with birds or other animals.”

Across California health departments, the alarm level rose a notch when Alameda County reported on November 19 that a child with mild respiratory symptoms had tested positive for H5N1. No one knew how the child had contracted bird flu. Then Marin County reported on December 10 that a toddler who had drunk raw milk containing H5N1 was ill with fever and vomiting. Following California Public Health suggested protocol, Marin sent patient samples to the state lab and to the Centers for Disease Control, which found the samples had too little virus, or were too old, to distinguish everyday Influenza A virus from bird flu virus. The child’s family members did not become sick, which eliminated human-to-human transmission as a source, but the illness is listed as “suspected” H5N1.

For the scientists who track diseases, a mystery is never a good thing. While human transmission has never been known to happen since H5N1 was first isolated in China in 1997 — when avian flu had a 50 percent mortality rate among the people infected — every outbreak raises the concern that the virus may mutate toward easier human transmission.

Most of the 61 H5N1 cases in the United States are in dairy or poultry workers, but several are of unknown origin. And until last Friday, U.S. cases were marked by mild symptoms that soon resolved. But a man in Louisiana was hospitalized with H5N1, state officials announced on December 13, adding that he was older than 65 and had underlying medical conditions that complicated his flu symptoms. They believe he caught H5N1 from sick or dead birds in his backyard flock. However, before this case, the other hospitalized patient was a healthy Canadian teenager who developed conjunctivitis and then a severe lung infection in late November. His vector of infection remains unknown.

In Santa Barbara, the Mosquito and Vector Control Management District monitors for mosquito-borne viruses, which do not include H5N1. However, biologist Brian Cabrera, general manager for Vector Control, said his staff pick up dead birds on a regular basis to test for encephalitis-causing viruses. They have been asked to be sure to wear protective gear. “You never know,” Cabrera said, “especially now with the increase in bird flu virus that’s circulating.”

Cabrera added that during the COVID pandemic, the governor’s emergency declaration enabled government groups to hold meetings remotely on video. This was the type of streamlining he expected to occur now.

As we all learned during COVID, viruses mutate. An October study published in Nature reported that the virus affecting the first known U.S. case — a dairy worker in Texas — had mutations that enabled it to be transmitted among the cows through airborne droplets. The researcher, Yoshihiro Kawaoka of University of Wisconsin-Madison, exposed ferrets to the virus which resulted in a 100 percent mortality rate.

Susanne Rust, a reporter with the Los Angeles Times, interviewed experts who noted that the mutated virus in the Texas worker has disappeared, either because it stalled out in the eye — if that’s how he contracted it — or perhaps he’d had a previous bout with H1N1, the swine flu from 2009, which is similar enough to H5N1 for the body to set off an immune response.

The state Department of Public Health (CDPH) said the more than 30 H5N1 cases reported among California dairy workers indicates that raw milk can cause infections in humans. “While the overall risk to the public remains low,” the CDPH press office said, “bird flu viruses can change and gain the ability to spread more easily between people.”

This was thought to require multiple mutations, but Rust cited a new study in Science on December 5 that indicated only one change in the H part of H5N1 could open the door to widespread human infection.

Scripps Research Institute scientists James Paulson and Ian Wilson had tinkered with proteins on the surface of the virus, using information from outbreaks that had jumped the bird-human divide, Rust described. They found that a single mutation could accomplish this today. However, the same mutation had occurred in the past with no ill effects, Paulson said, as it was a slightly different virus then. It’s the nature of a virus to change and change again, so there’s a chance the Scripps experiment won’t be duplicated in the wild.

With roughly 1,300 dairy farms, the “nation-state of California,” as Newsom likes to say, produces about 20 percent of the nation’s milk. California is taking precautions through the emergency declaration to hold H5N1 back.

Premier Events

Fri, Jan 09

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Intention Setting & Candle Making Workshop

Sun, Jan 11

3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mega Babka Bake

Fri, Jan 23

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Divine I Am Retreat

Wed, Jan 07

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBAcoustic Presents the John Jorgenson Quintet

Thu, Jan 08

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

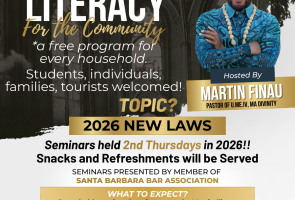

Blueprints of Tomorrow (2026)

Thu, Jan 08

6:00 PM

Isla Vista

Legal Literacy for the Community

Thu, Jan 08

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Music Academy: Lark, Roman & Meyer Trio

Fri, Jan 09

8:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Herman’s Hermits’ Peter Noone: A Benefit Concert for Notes For Notes

Fri, Jan 09

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ancestral Materials & Modernism

Fri, Jan 09

6:00 PM

Montecito

Raising Our Light – 1/9 Debris Flow Remembrance

Fri, Jan 09

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Barrel Room Sessions ~ Will Breman 1.9.26

Sat, Jan 10

9:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Rose Pruning Day | Mission Historical Park

Sat, Jan 10

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Konrad Kono – Live in Concert

Fri, Jan 09 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Intention Setting & Candle Making Workshop

Sun, Jan 11 3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mega Babka Bake

Fri, Jan 23 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Divine I Am Retreat

Wed, Jan 07 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBAcoustic Presents the John Jorgenson Quintet

Thu, Jan 08 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Blueprints of Tomorrow (2026)

Thu, Jan 08 6:00 PM

Isla Vista

Legal Literacy for the Community

Thu, Jan 08 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Music Academy: Lark, Roman & Meyer Trio

Fri, Jan 09 8:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Herman’s Hermits’ Peter Noone: A Benefit Concert for Notes For Notes

Fri, Jan 09 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ancestral Materials & Modernism

Fri, Jan 09 6:00 PM

Montecito

Raising Our Light – 1/9 Debris Flow Remembrance

Fri, Jan 09 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Barrel Room Sessions ~ Will Breman 1.9.26

Sat, Jan 10 9:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Rose Pruning Day | Mission Historical Park

Sat, Jan 10 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.