Macduff’s Cloud Vision

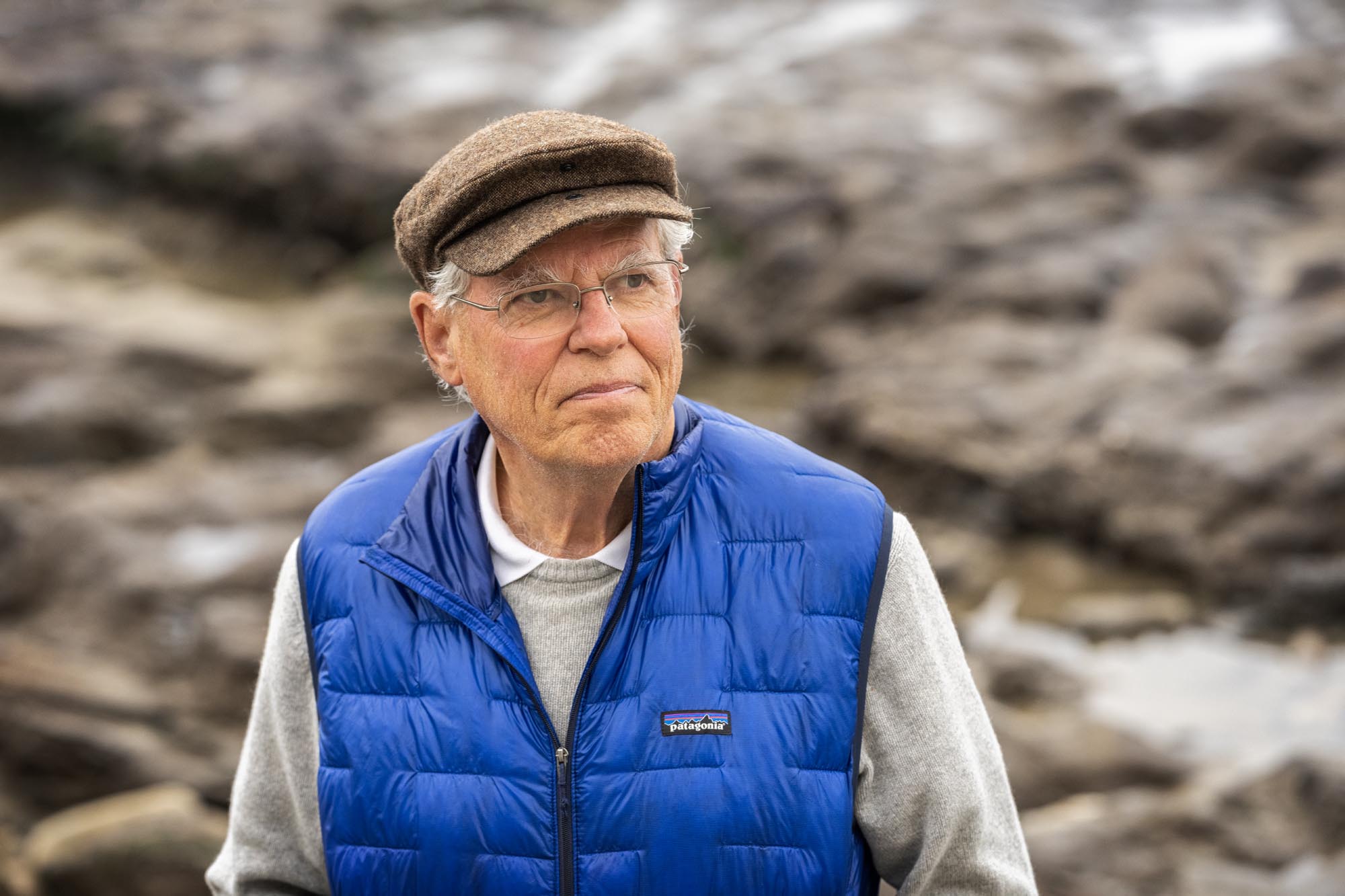

Meet the artist behind our photogenic cover story this week: Macduff Everton. He’s done everything from lifestyle, landscape, travel, and fine art images from around the globe as a National Geographic photographer and visual anthropologist.

What inspired these cloud photos and what did gathering all of these shots take?

It’s not a series per se. When I shoot landscapes, clouds hopefully show up. Using a panoramic camera, I need to hold the camera level, so the sky is often half the image. If there aren’t clouds, half the image is boring. I need to pay attention to composition and every part of my canvas, or, as fellow artist Arthur Wesley Dow taught Georgia O’Keeffe, the importance of “filling a space in a beautiful way.”

What is some advice you’d give to aspiring photographers?

I’m writing about this. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes, then learn from them. If you promise someone a photo, be sure to deliver. Digital is so different from film. I could go a year before I saw images. I’d try something and when I finally saw film, I’d forget what I was trying to do. My first editor at National Geographic advised me that when I found something really good, really shoot it. Then shoot it six more different ways.

In order to support my visual anthropological work with the Maya, I needed to make money. At first, I did construction, working as a carpenter, cement work, foundations, stone work. But then I started working as a wrangler and packer, mule skinning, eventually running a pack station out of Golden Trout Wilderness. Living in the backcountry, on horseback most days. It really helped refine my sense of light and color, something impossible to re-create looking at a screen, a hand-held device. I have good peripheral vision because I use it. I know light. I learn what the weather might do.

Sitting in the saddle for 16 hours prepares me for when I started getting editorial assignments and flying all over the world sitting in economy, then landing and renting a car, driving six hours to a location, then commencing to shoot before checking into a hotel.

Respect. Respect your subjects. Try to work with editors that respect your work.

What do you usually like to photograph with?

I like to photograph with my wife and, ideally, the rest of my family accompanying me.

You have a book called The Modern Maya. What are some of your fondest memories from the Yucatán and living there?

There aren’t many documentary photography projects that span more than 40 years, especially working with the same individuals and their families. This book is their stories. While most history chronicles the famous, this is about the lives of ordinary people who are the soul of their culture. The Italian reporter Tiziano Terzani wrote, “Facts that go unreported do not exist if no one is there to see, to write, to take a photograph, it is as if these facts have never occurred, this suffering has no importance, no place in history. Because history exists only if someone relates it.”

When I first visited Yucatán, I wanted to do a day in the life modeled on the Life magazine pieces. When I started living with different families, I found their lives so different that a day wasn’t enough to convey what they did. A day became a week, then a season, then a year. After twenty years, the University of New Mexico Press published The Modern Maya: A Culture in Transition. I thought I was through and I could move on to another project. But so many significant events followed that I realized I had to keep telling my friends’ stories. For example, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) put nearly three million Mexican farmers out of work. For an agrarian culture, this had a devastating effect — so much of Maya cultural knowledge, built up over thousands of years, is connected to their agricultural practices and ceremonies. If they stop farming, they lose the understanding of their relationship with the land that’s built into their farming system. When young people aren’t learning from their parents in the field — if you skip a generation — that information is lost. Then there are the new Evangelical sects who forbid their members to participate in community activities in which the entire village had always taken part, tearing communities apart. Tourism became a major industry and monoculture, transforming the Caribbean coastline into some of the most valuable real estate in North America. And at the same time, the narcotraficantes appeared with their drugs and violence.

I had questions about the prevailing hypothesis on the collapse of the ancient Maya. I found an emerging group of botanists, agroecologists, epigraphers, archaeologists, and ethnographers studying the ways in which the Maya cultivated and managed their land. As their separate discoveries are combined, we see just how many widely believed assumptions about the Maya lack nuance or are even incorrect. So, I met with two archaeologists while they conducted their field investigations and talked with them about the hypothesis that environmental degradation led to the collapse of the Maya. What I found starts the book.

People often look to history to find correlations that match their current conditions — so the so-called collapse of the Maya has been blamed on overpopulation, environmental degradation, warfare, revolts, disease, or climatic changes (such as prolonged drought). But many archaeologists now believe there was a cultural transformation — a profound political, economic, and demographic shift (think Detroit, for example, for a contemporary equivalent of a city abandoned). The Maya voted with their feet. In fact, archaeologists today argue that Maya civilization flourished and even blossomed during the Postclassic period.

My fondest memories are living with my friends in their homes, working with them in the field, telling their stories, and, finally, with the help of my neighbor Isaac Hernandez, translating and publishing it in Spanish so they could finally read it after the two volumes in English, the latest with University of Texas Press: The Modern Maya Incidents of Travel and Friendship in Yucatán — part of The William and Bettye Nowlin Series in Art, History, and Culture of the Western Hemisphere.

What was your UC Santa Barbara experience like, and what was your favorite thing to do on campus?

I loved UCSB. I was going to take a gap year when I graduated from high school. Left S.B. High at 17 with my surfboard to go surfing in Biarritz, France, but, by a series of small steps, hitchhiked around the world. Never would have set out to do it as a goal — too daunting. Literally picked up a camera from an American tourist on the Danish island of Bornholm who said he didn’t want to look like a tourist, and by the time I got to Japan, I sold my first two stories: one on Burma, the other on Southeast Asia. It changed my life. So, I took a gap decade, even working as artist in residence for the state of Washington teaching K-12 for two years. But I was already involved in my Maya project and wanted feedback. College of Creative Studies at UCSB was ideal. I loved it. I worked horses and mules for the season, then jumped full into academia. It was so much fun that I stayed on for an MFA. That, and I promised my son that he could graduate from S.B. High if he kept his grades up. The alternative was cowboying winters in the foothills of the Sierras, and he did not want to go to high school in Porterville. I’m glad he didn’t. Graduate school was even more fun.