I’m typing this interview with Father Gregory Boyle S.J. — founder of the L.A.-based gang rehabilitation and re-entry organization Homeboy Industries and author of Cherished Belonging: The Healing Power of Love in Divided Times — not just because he’s coming to UCSB’s Campbell Hall to speak on December 3, but because he’s a big reason I’ve been a typist for more than 40 years.

Fr. Greg was my teacher at Loyola High School in Los Angeles from 1978 to 1981, where he taught composition and theology and also guided me into editing a school magazine. Thanks in part to this much-appreciated influence, I’ve (mostly) enjoyed a long and (mostly) successful career as a writer, editor, and publisher. Fr. Greg has remained a good friend of my entire family in the decades since. How nice to be able to thank him in person while I tell you about him and his new book!

Boyle started Homeboy Industries in 1988 while he was a Los Angeles parish priest in one of the most gang-intensive neighborhoods in the country. While trying to preach, heal, and help, he discovered the maxim that “nothing stops a bullet like a job.” So, he created jobs for gang members. He founded what has become Homeboy Industries, and now includes a bakery (perfect for holiday gifts, hint, hint), a café, a solar-panel installation business, electronics recycling, silkscreening, dog-grooming, and more.

Homeboy’s center in downtown Los Angeles greets people each year with a sometimes hard-to-believe amount of love, acceptance, tenderness, and community, and has helped thousands of gang members heal and move forward. In May, Fr. Greg received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Biden.

I was going to start with, “What the heck do we do now?” but I’ll get to that. Looking back, when did you first understand that “we belong to each other” was really the root of what Homeboy was and could be?

It comes from something Mother Teresa said that I used to quote incorrectly or at least not completely. The fuller quote is “if [we have] no peace … it is because we’ve forgotten that we belong to each other.” So, there’s that sense that belonging can address all the vexing complex social dilemmas that we have. My friend, Padraig Ó Tuama, who was in the Troubles [in Northern Ireland], says that the Troubles were really “belonging gone wrong.” That’s what gang allegiance and membership is. It’s just belonging gone wrong. Because everybody who doesn’t know gangs will say, “Oh, they just want to belong.” Well, yeah. But hopeful kids join the Boy Scouts. The kids who can’t imagine a future for themselves adhere to a gang. And so, it’s really belonging gone wrong because no hopeful kid in the history of the world has ever joined a gang. It’s about hope and a lethal absence of hope. How do you infuse hope to kids for whom hope is foreign? The goal is not a behaving community, but a community of cherished belonging.

I’ll follow-up the cherished belonging [of the new book’s title], but going back to the early days of Homeboy, was there ever a time when you were on your cruiser dodging bullets that you sort of doubted that this wasn’t going to work out?

No. I never really cared. I learned early on that, you know, success and failure [are] kind of . . .who cares about that stuff? Again, Mother Teresa said, “We’re not called to be successful. We’re called to be faithful.” So, once you kind of log on to the thing that you want to be faithful to, which is [that] you want to love as we are loved without measure and without regret. Once you do that, you go; success or outcomes, that’s not my concern. I’m just going to do the next loving thing. I find that kind of freeing. Otherwise, you end up wanting to only work and walk with people who are most likely to succeed. So early on, I just stopped caring about that stuff.

As long as I’ve known you, you’ve always used stories and humor to teach and to share. Why do you think that works so well, or why do you think that informs your way of getting a point across? Is that conscious or is that just you?

Well, maybe [it’s] because I’m an audience member myself. And my hope is you will make me laugh, and you will make me cry, and you will help me move beyond the mind I have. And so, I’m an audience member, and so that’s what I want from people. Sometimes I’ll see a movie, and I’ll go, wow, there wasn’t one funny moment, which means it’s kind of, uh, not human. And, like when people in the gospel ask Jesus, “Tell us about the reign of God,” he ends up telling them stories about themselves. And so, people don’t listen otherwise unless you’re telling stories. As soon as you start to tell a story, people — no matter if it’s a good story or bad or told well or not — they’re with you. You can throw out content as in, why don’t you think about this? But you better move quickly to a story. Or move quickly to something that will make them laugh. Because that you know, our attention spans aren’t great because we’re human.

I’ve always wanted to ask you this: All of the stories of the homies, the people you’ve met in your work, what do they think about you telling them? Do they say, “Hey, that was me in that story!” Or are they going, “Hey, I don’t want to be in there.”

I’m kind of astounded at how few gang members actually read my books. They’ll read them when they’re locked up because; otherwise, they’re not much readers. Although I have to admit, especially with this book, I had more homies asking if they could get a copy. I’ve never had that before. But I tell them that I’m only going to give you this book if you actually read it.

I’ve read all your books, and they all have lots of stories. But this book seems to have a little bit more emphasis on a sort of philosophy or a sense of, “Let me try and suggest some ways you can start thinking about things.” Not that the other books didn’t have that, but this one sort of seemed to start from that at the start. Is that how it came about?

This book, unlike the other three, was born of the moment in which we’re in. And so how do we name things? And what do we think we’re doing? And what do you think that is? And where does that come from? Since I finished writing it, I’ve kind of had a lot more thoughts, especially after November 5, which happened to be the publication date!

Wait, really?

Well, it was supposed to have been October 8, but the damn author wouldn’t get his act together!

Well, that happens. We do that.

Anyway, I kept getting asked the question, you know, about the current times without mentioning his name. It was always questions about that. And so, this book is kind of a starting point to process where we might go. And even in the light that he won, it’s kind of like, how do you see this, and who are we, and what does it mean?

A key part of the book’s contention is that all people are innately good. No exceptions. And the follow-up to that is that beliefs such as racism, misogyny, hatred of the other, or the choices people make, are always a result of not being healthy or whole or well. For me, that made a lot of sense, but where do we go from there? What can I do going forward to see that those unhealthy, unwell, unwhole people become healthy and well?

Well, at Homeboy, people are cherished into seeing their own goodness. And you can really cherish people into health where they’re flourishing. Yeah. My new friend the Surgeon General [Vivek Murthy] said mental health is the defining health issue of our time. And so, when I look back at that statement and then I look at what we’ve been living through, certainly since the pandemic, which exacerbated everything. Look at the things that have just completely gone crazy. Hate crimes up 300 percent. Homelessness, fentanyl overdoses, and suicides. You can talk about smash and grab crime in Los Angeles. [So] I would say, if somebody wants to be governed by an authoritarian, that’s not a really baseline healthy thing. That’s not a judgment call. That’s a health assessment. That’s like me telling you, “Hey, I’m worried about that cough. It just sounds bad.” You know? So, it’s really a concern for you. I don’t think it’s elitist. I don’t think it’s condescending. I think none of us are well until all of us are well.

I always say the bravest people I’ve ever met are the people who stand up and say, “I need help, and I’m going to come to you for it.” The frustration for us now is that even if we take it as fact that Trumpists have a mental health issue, they would strenuously disagree with me, and there’s nowhere for me to go with that. What can I do about the fact that these people have a mental health issue according to this idea?

If we think the change is about winning the argument, persuading somebody to come to my side, that’s not the goal. The goal is to cherish people so that they can enjoy the joy there is in cherishing themselves and others. So, it’s not, “Let me point out to you how unhealthy you are.” You know, I just think as a guide, you know, things are indicators. [Just as an example,] homelessness is explosive. So, when we want to reason with it, we go, “Let’s call them the unhoused because it’s only about housing.” And you just go, wow. “Have you ever met a homeless person?” It’s not so much about absence of housing as the absence of relationships. And then that becomes the place of how do we walk each other home to health?

Right. I guess my point is that if I wanted to reach out to a person I knew held Donald Trump and his ideals in high esteem, I have no basis of connection there. I can say I love you and I cherish you and I think you’re an innately good person, but also that you’re not healthy, you’re not whole. They’re not going to agree with me.

I don’t think you need to say it exactly. I mean, for example, we had homies who voted for Trump. And, they would say things like, “I don’t want my fifth-grade son to go to school and come home a girl.” You can, you know, grab him by the lapel and say, “Are you out of your mind?” But I mention in the book that nobody healthy spreads disinformation, but nobody healthy buys it. It’s a little bit like a cult. You don’t hate them. You have to work to convince them … what do they call it? Deprogramming. But nobody healthy joins the cult. And this is a cult. So, then they start going, “But the price of eggs.” And I go, “Okay, no.”

It’s not like somebody voted for Mitt Romney as opposed to Barack Obama. For the first time in my 52 years of voting, in 14 presidential elections, it’s the very first time that the choice was someone who’s a healthy adult in the room and someone who isn’t. I’ve never had that choice. Because in the past, you always had two relatively healthy adults in the room. Really, there was none of that because this was such a disruption, because it’s never happened before. And now, quite frankly, when you have RFK [Jr.] who is going to be the head of [the Department of Health and Human Services], you just go, this is a real mental health issue writ large. And will be quite damaging. But I think we resist without demonizing. We hold out the principles that I believe in, which is everybody’s unshakably good, including the one people overwhelmingly voted for. [He’s] unfit to be president, but worthy of our compassion. You don’t need to be a psychiatrist to know that he is ill, but you have to be well to know that he isn’t well. I mean, the women in the parish at Dolores Mission [in L.A., Fr. Greg’s original posting] are monolingual and not formally educated. But because they’re healthy adults in the room, they recognize, no, that nobody healthy says this.

A lot of the things that you’re calling on people to think about have a real connection to God. And I’m curious how you approach non-believing folks, because not everyone reading this believes in or has God in their life in any particular way. They might not follow a particular faith or creed or religion, and they don’t feel like that is a motivating factor for them. Do your ideas work there, or do you think there’s a modification if someone doesn’t see God as some somewhere in the center of it?

There is a longing in this country, and having just come back from Tulsa[, Oklahoma], and Appleton, Wisconsin, I see that there’s a longing. People want to align themselves to a larger love. And that cuts across all areas. Rumi used to say, “Love is God’s religion.” And so, I think that connects to somebody who’s an atheist. In the end, you want to connect to your longing. And you can get there as a Buddhist or as an atheist. Or as a Catholic.

So let’s talk about Tulsa and Wisconsin and places reddish. How do you think a talk like yours goes over if you’re in a room full of MAGA devotees or you’re at a KKK rally? I don’t mean to be too extreme about this, but at Campbell Hall, when you sit down at UCSB, everyone in the room will be on your side.

I was in the Tulsa Performing Arts Center at 10:30 in the morning, and there were 2,000 people there. I had thought, “God, I’m in a red state. Who’s gonna come to this thing?” Well, it was a [blue] puddle in a red sea. A theater was filled in Appleton, Wisconsin. And, again, I was kind of going, “Who’s going to be here? Are they bringing bags of rotten vegetables?” But again, these are people who have read the books. Sure. So, they’re already kind of on that page. But then they go home and talk to their, you know, uncle. They are the ripples in the pond. It’s not us and them, but how healthy are we.

Barack Obama asked this question in a way that I found really liberating. He said, “When did it become okay?” And then fill in the blank. To lie about this. To say that. To call her trash. When did it become okay? But my thing isn’t that we’ve lost our moral compass. My thing is, no one, no country that’s healthy applauds that kind of thing. I don’t disdain them. They’re not a basket of deplorables. But there’s nobody who’s deplorable. But, you know, we’re not all that healthy. If we deal with all that in terms of health — that is, you’re not you’re a bad person because you have lung cancer. That doesn’t make any sense. But as soon as we abandon the idea that there are good people and bad people and that there is no us and them, there’s just us, once you’re kind of in that world, then it’s not about the homie who was afraid that his son would come home as his daughter. Look at it not as, I need to win him over. Work on yourself. Don’t run away from it. Tend to it. And then what will happen? It doesn’t mean suddenly [they] become a Democrat.

Right. But the active verb is “work” on yourself. And I guess for us, the frustration is we want to do something, and we can start on ourselves, sure. And at the end of the day, I can believe that everybody is unshakably and perfectly good without exception, but there are still 78,000,000 people who think they’re not only perfectly mentally health healthy but think the entirely opposite thing. I guess what I’m just sort of frustratingly grabbing for, from you and everybody, is a practical step forward.

I think only love makes progress. And that in the end, it doesn’t mean we don’t resist. But we know that progress will only happen if we’re loving. And if we discover loving is our home, then you are never homesick. And so, this is how you lead. You just put one loving foot in front of the next. But all the while, love has to be clear. You know, it’s not okay that you storm the Capitol. It’s not healthy. We do this all the time [at Homeboy] when people are acting out and outrageous in their behavior, because they’re not well and they’re not whole. And I think it’s a better kind of stance than saying, you know, the cruelty is the point. No human being thinks cruelty is the point. It’s just telling you, woah — somebody’s really not well. And when they are, they’re worthy of our compassion. And that’s the essential thing, it seems to me. Because then you know that the answer to every question is compassion.

It’s a big ask.

I know it is, but I don’t know any other solution.

Tickets are sold out for Fr. Greg’s talk at 7:30 pm December 3, but because of high demand, there will be a simulcast in Buchanan Hall 1920 on the UCSB campus. Simulcast tickets are $5, and after the talk, ticketholders can purchase copies of the book and get it signed by Fr. Greg. For information and tickets, see https://bit.ly/40WADFh or call Arts & Lectures at (805) 893-3535.

Note: A shorter version of this interview appeared in the print edition of the Santa Barbara Independent.

Premier Events

Fri, Jan 09

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Intention Setting & Candle Making Workshop

Sun, Jan 11

3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mega Babka Bake

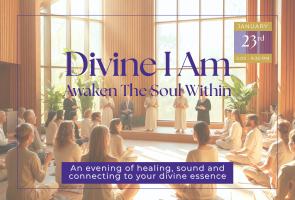

Fri, Jan 23

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Divine I Am Retreat

Wed, Jan 07

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBAcoustic Presents the John Jorgenson Quintet

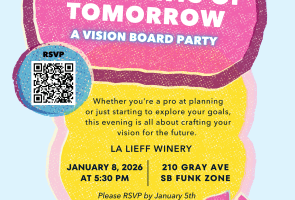

Thu, Jan 08

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Blueprints of Tomorrow (2026)

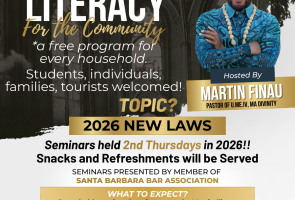

Thu, Jan 08

6:00 PM

Isla Vista

Legal Literacy for the Community

Thu, Jan 08

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Music Academy: Lark, Roman & Meyer Trio

Fri, Jan 09

8:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Herman’s Hermits’ Peter Noone: A Benefit Concert for Notes For Notes

Fri, Jan 09

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ancestral Materials & Modernism

Fri, Jan 09

6:00 PM

Montecito

Raising Our Light – 1/9 Debris Flow Remembrance

Fri, Jan 09

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Barrel Room Sessions ~ Will Breman 1.9.26

Sat, Jan 10

9:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Rose Pruning Day | Mission Historical Park

Sat, Jan 10

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Konrad Kono – Live in Concert

Fri, Jan 09 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Intention Setting & Candle Making Workshop

Sun, Jan 11 3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mega Babka Bake

Fri, Jan 23 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Divine I Am Retreat

Wed, Jan 07 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBAcoustic Presents the John Jorgenson Quintet

Thu, Jan 08 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Blueprints of Tomorrow (2026)

Thu, Jan 08 6:00 PM

Isla Vista

Legal Literacy for the Community

Thu, Jan 08 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Music Academy: Lark, Roman & Meyer Trio

Fri, Jan 09 8:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Herman’s Hermits’ Peter Noone: A Benefit Concert for Notes For Notes

Fri, Jan 09 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ancestral Materials & Modernism

Fri, Jan 09 6:00 PM

Montecito

Raising Our Light – 1/9 Debris Flow Remembrance

Fri, Jan 09 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Barrel Room Sessions ~ Will Breman 1.9.26

Sat, Jan 10 9:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Rose Pruning Day | Mission Historical Park

Sat, Jan 10 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.