How unreasonable, the Age of Reason, especially for an illiterate — if wildly, imaginatively thoughtful — peasant. AK Blakemore’s new novel The Glutton might be based on a wisp of a fantastical, 18th-century real person, but widens into a shocking fairy tale as vivid as a Breughel or Bosch.

Here’s how the book’s beyond an anti-hero protagonist introduces himself, “The Great Tarare. The Glutton of Lyon. The Hercules of the Gullet. The Bottomless Man. The Beast.” Indeed, as Tarare relates his life of woe-on-the-go to his hospital nurse Sister Perpetué, we learn of his hardscrabble upbringing not shy of maternal care; a shocking, near-death beating keyed to a betrayal after his first kiss; and a life with a band of con men, courtesans, and schemers who have no problem using his disgusting hunger as the main act of their traveling sideshow.

The Revolutionary era France of The Glutton is pitiless, so why wouldn’t crowds come to gawk at the young man who devours as much of everything he is fed? Live rats are far from the worst of it — this isn’t a book for the squeamish. But, of course, hunger is one of our most adaptable of metaphors, and Blakemore’s poetic sense (she does publish poetry too), lets Tarare muse mightily, often with a keen political edge. For instance, he wonders, “Who feasts and who starves, entirely a matter of chance — chance then reified and made sacred, made other than it is, through God and debt and machines. And whips.”

Peasant fatalism isn’t a bug, but a feature. Early in the book, after a cruel summer, Blakemore writes, “And soon it is winter again, and everyone thinks everything is going to get worse forever, because it certainly won’t get better or stay the same. An immutable law of nature being — as gentlemen-scholars of Paris are saying at this time — flux.” Her cold eye does allow a few glimmers of at least pleasantness, whether that be out of mercy for Tarare or her readers. After all, even Sister Perpetué wonders, “The memoirs of a cannibal … who would wish to read such a thing?”

That’s the rub, of course. Tarare’s innocence and abhorrence are inseparable, yet it’s hard to deny their pull, as we hope there might be a why (although the novel never solves anything easily for us), as we hope there might be a way out (although we pretend that’s not death, knowing all we know). Just as Tarare can feel refreshed after some time bathing in a river, we get to swim in Blakemore’s gorgeous prose, from descriptions like “a dither of midges” to retorts to a prolix person like, “There’s no Sunday for your tongue.”

And then there’s the hankering for family, a hunger Tarare never gets to quench. He loses his mother; his itinerant, criminal troop eventually disperses; even the army ends up a place where he becomes a butt of an elaborate international joke. In his time as a soldier, after getting busted for stealing other’s rations, a Rousseau-reading, self-admitted “liberal” aide-de-camp still avers, “What is a peasant doing with preferences, with appetites? With distinguishing characteristics? A peasant with preferences is a monkey with an orrery. A sheep with a china teapot.”

The Glutton is a book where Pangloss would go to die. Blakemore leavens the misery and loss, if a bit, by resurrecting language — at one point a have-not character only half-jokes, “Perhaps I learned to talk so prettily in the leisure my vagrancy affords me.” The book’s pretty prose requires a dictionary by your side, leaving you to learn the likes of, and this is just a few: bocage, smalt, goliard, thimblerig, gleets, doleance, bandog, chine, jugulate, Tophet, mouchard, gurns, flensed, baldachin, charivari, Upiór. Blakemore is sure to float your coracle with her diction.

Blakemore is also certain to make you rethink your world and your relationship with it (to it is far from the wrong prepositional phrase, no?). At one point a character suggests, “Looking is a flavour of taking.” How can reading not be the same? At a critical plot point in the book Tarare’s gang gets to wander through an already ransacked aristocrat’s mansion. Even torn apart, it’s grander than anything impoverished Tarare has ever seen. (He has no Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous to learn of his place.) But then, the young man who can never consume enough has this revelation: “Perhaps a precondition of true beauty is surprise, he thinks: real beauty must seem as if it has fallen abruptly from the sky, or else come from deep inside the earth — some place where it had shone secretly and unseen, until you came along and saw it…. they are luxurious, certainly — but luxury is the opposite of surprise.”

This review originally appeared in the California Review of Books.

Premier Events

Wed, Dec 31

9:00 PM

Santa barbara

NEW YEAR’S Wildcat Lounge

Wed, Dec 31

6:15 PM

Santa Barbara

NYE 2026 with SB Comedy Hideaway!

Wed, Dec 31

9:00 PM

Santa barbara

NEW YEAR’S Wildcat Lounge

Wed, Dec 31

10:00 PM

Santa Barbara

In Session Between Us: Vol. I NYE x Alcazar

Wed, Dec 31

10:00 PM

Santa Barbara

NYE: Disco Cowgirls & Midnight Cowboys

Thu, Jan 01

7:00 AM

Solvang

Solvang Julefest

Thu, Jan 01

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Polar Dip 2026

Sat, Jan 03

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

No Simple Highway- SOhO!

Sun, Jan 04

7:00 AM

Solvang

Solvang Julefest

Thu, Jan 08

6:00 PM

Isla Vista

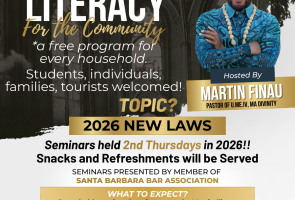

Legal Literacy for the Community

Fri, Jan 09

6:00 PM

Montecito

Raising Our Light – 1/9 Debris Flow Remembrance

Wed, Dec 31 9:00 PM

Santa barbara

NEW YEAR’S Wildcat Lounge

Wed, Dec 31 6:15 PM

Santa Barbara

NYE 2026 with SB Comedy Hideaway!

Wed, Dec 31 9:00 PM

Santa barbara

NEW YEAR’S Wildcat Lounge

Wed, Dec 31 10:00 PM

Santa Barbara

In Session Between Us: Vol. I NYE x Alcazar

Wed, Dec 31 10:00 PM

Santa Barbara

NYE: Disco Cowgirls & Midnight Cowboys

Thu, Jan 01 7:00 AM

Solvang

Solvang Julefest

Thu, Jan 01 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Polar Dip 2026

Sat, Jan 03 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

No Simple Highway- SOhO!

Sun, Jan 04 7:00 AM

Solvang

Solvang Julefest

Thu, Jan 08 6:00 PM

Isla Vista

Legal Literacy for the Community

Fri, Jan 09 6:00 PM

Montecito

You must be logged in to post a comment.