George Thurlow Reckons with His El Salvador Days

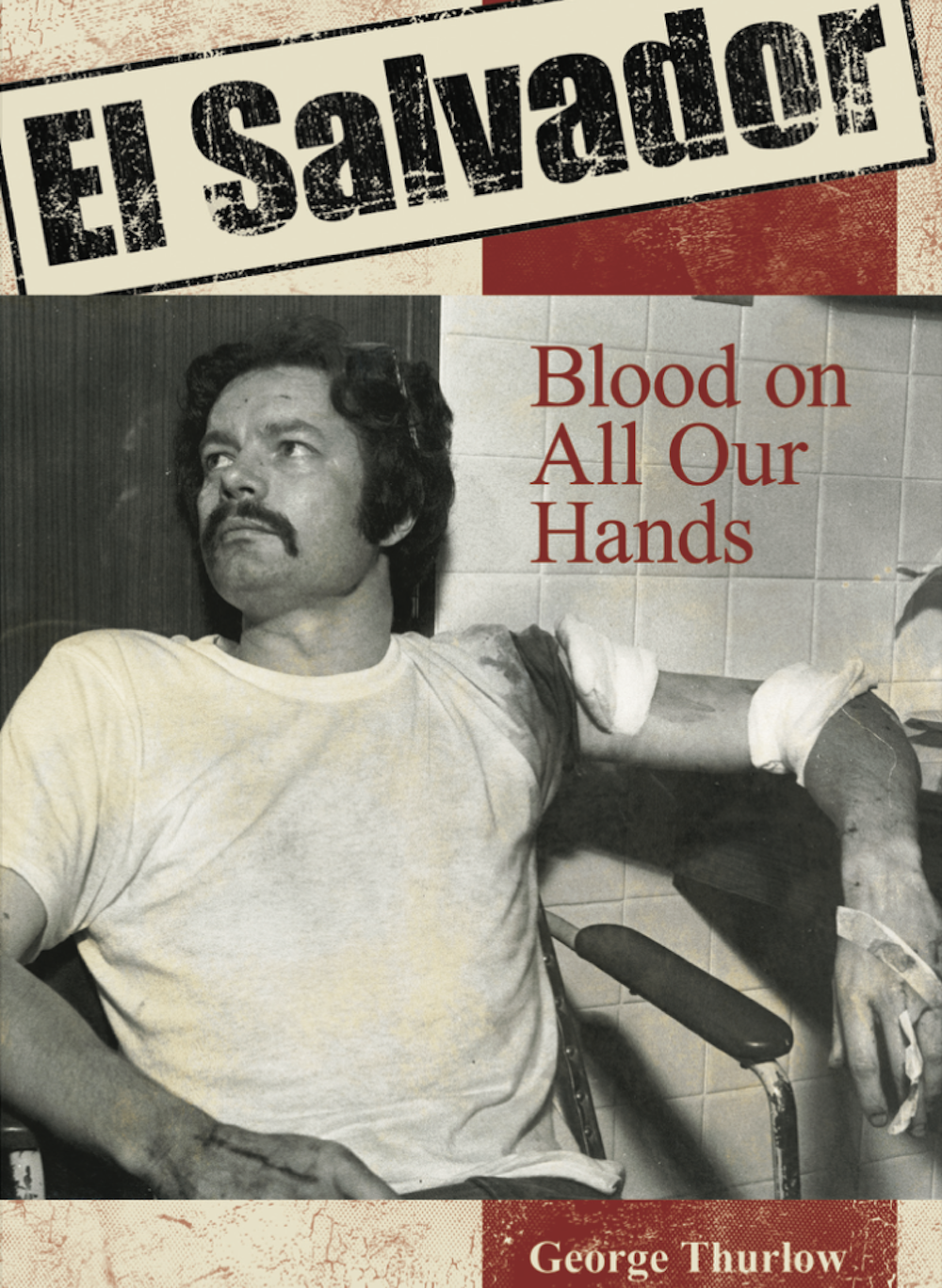

Former Publisher, Retired UCSB Assistant Vice Chancellor Pens Soul-Searching Memoir ‘El Salvador: Blood on All Our Hands’

When George Thurlow was an aspiring war reporter covering the rise of leftist guerillas against the notoriously brutal, American-backed government of El Salvador in 1981, the gunshot he suffered during a firefight on his fourth day would be the 29-year-old’s easiest injury to heal.

The wound left open, even four decades later, is the memory of Thurlow’s driver Gilberto Moran, who, also 29 years old, was killed in that same incident. That they, and a severely

wounded Associated Press photographer, were gunned down by the police — possibly accidentally, likely intentionally — only adds haze to Thurlow’s attempt to recover from, make

sense of, and forgive himself for those brief moments in time.

That grappling continues to this day for Thurlow, who’d leave the front lines but stay in journalism, eventually becoming the publisher of the Santa Barbara Independent from 1994 to

2006 before moving on to be the assistant vice chancellor in charge of alumni issues at UCSB, his alma mater. But a big serving of catharsis comes in his new book, El Salvador: Blood on All Our

Hands, a vivid retelling of his very brief war reporting career and the emotional soul-searching he’s endured in trying to find Moran’s grave and determine what really happened.

“I thought it was gonna be Vietnam,” said Thurlow of the 12-year-long conflict that ended in 1992. “I wanted to be there early as a journalist to cover it because, if it was going to be another Vietnam, the journalism out of Vietnam was terrific. But it didn’t turn into Vietnam. We just killed 70,000 people.”

Thurlow’s reporting on the blatant atrocities being committed by the Salvadoran government against their poor citizens would be shocking even if they were discovered in retrospect. But the American government was well aware that these crimes were happening in real time, and kept funding the murders in the name of fighting communism. It was such a mess, from the top of the Reagan administration to the death squads on the bottom, that most just want to forget it all.

“There’s no book really like this,” said Thurlow, explaining that there are very few English-language publications on the civil war. “This is a different perspective. I’ve talked to many of the journalists who were there, and none of them have any interest in writing a book. I get the sense that many of them don’t want to revisit it.”

Much of the story is about the ambitions of a young writer from Visalia, California, trying to make a name for himself. While at UCSB, Thurlow was empowered by pepper sprayings during the bank-burning days of Isla Vista in 1970, and then learned newspapering on the staff of the Santa Barbara News & Review before moving on to the Woodland Daily Democrat, whose publisher baked his Salvadoran mission. But Blood on All Our Hands is more broadly about the failures of parachute journalism, in which foreign correspondents drop into the middle of complex scenarios needing to deliver the salacious stories that sell at home.

As a former aspiring young journalist myself — and one who dropped in for short stints as a twentysomething to cover postwar geopolitics in Africa and the Caucasus — I very much relate to Thurlow’s early ambitions and later reflections. Indeed, George was my publisher at this newspaper when I embarked on those overseas adventures, and knowing that he’d been shot added inspirational gravitas to his standing in my emerging reporter mind.

But despite the shortcomings of parachuting in to report a story, we both believe that more journalism is almost always better. “Anything we can do to improve the discussion, particularly about the U.S. role, is important,” said Thurlow. “What’s going on in Gaza? That’s the one if you were young and wanted to get ahead of a story that’s particularly brutal and going to go on for a while.”

Not that El Salvador’s story ever reached a happy ending, as the effects of their civil war gave way to the rise of criminal gangs. A crackdown instigated in 2022 by President Nayib Bukele has since imprisoned about 80,000 people, with due process mostly thrown out the window. Because of that, he’s been labeled an authoritarian autocrat, and yet he remains incredibly popular, as crime has decreased.

“We all know they’re breeding the whole next generation of gangs,” observed Thurlow of the massive lockup campaign. But it’s scarier than that. “We have to be careful, because this is a lesson for us,” he said. “People will support fascism if you get the guy off the corner who’s hassling you. And of course, he’s being emulated in all of these other countries.”

Though his book is done — with plans for a larger release in the future by the academic publisher Brill —- Thurlow’s story is not. Having retired from UCSB in 2020, his research continues, and he’s preparing for the day when the ghosts of Moran finally emerge.

“Emotionally and intellectually, I’m trying to prepare for the day that his grandson knocks on my door,” said Thurlow. “Then what do I do? Is it real? Do you have proof?”

The fog of war, it seems, only grows murkier with time.

See elsalvador81.com.

Premier Events

Sat, Nov 30

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Mosaic Makers Market – Small Business Saturday

Sat, Nov 30

6:00 PM

Carpinteria

Beau James Wilding Band Live at the brewLAB

Thu, Dec 05

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

First Thursday at Art & Soul in the Funk Zone

Fri, Nov 29

3:30 PM

Buellton

A Cowboy Christmas 2024

Fri, Nov 29

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Friendsgiving Country Night Black Friday

Sat, Nov 30

1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Grateful Gathering-Live Dead & Jerry@The Brewhouse

Sat, Nov 30

1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

1st annual Funk Fest

Sat, Nov 30

9:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Numbskull Presents: The Cure & More DJ Night

Sun, Dec 01

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Paseo Nuevo Tree Lighting Ceremony

Fri, Dec 13

12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Gem Faire

Fri, Dec 13

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBHS 2024 Annual Fall Dance Recital

Sat, Nov 30 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Mosaic Makers Market – Small Business Saturday

Sat, Nov 30 6:00 PM

Carpinteria

Beau James Wilding Band Live at the brewLAB

Thu, Dec 05 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

First Thursday at Art & Soul in the Funk Zone

Fri, Nov 29 3:30 PM

Buellton

A Cowboy Christmas 2024

Fri, Nov 29 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Friendsgiving Country Night Black Friday

Sat, Nov 30 1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Grateful Gathering-Live Dead & Jerry@The Brewhouse

Sat, Nov 30 1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

1st annual Funk Fest

Sat, Nov 30 9:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Numbskull Presents: The Cure & More DJ Night

Sun, Dec 01 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Paseo Nuevo Tree Lighting Ceremony

Fri, Dec 13 12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Gem Faire

Fri, Dec 13 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.