When I read the first volume of The Gulag Archipelago as a teenager, I lacked the education to fully understand it. My youthful worldview was unsophisticated, amounting to little more than “America Good; Soviet Union Bad.” I sensed that Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s book was important, a monumental achievement, but my understanding of the reasons why were hazy, and I didn’t fully grasp what a searing indictment of a political regime it was.

Looking back nearly a half-century later, as my country flirts with authoritarianism and one of America’s two political parties allows no scruple of decency, morality, common sense, or law to take precedence over the interests of its standard bearer — much as such things took no precedence over the Communist Party in Solzhenitsyn’s era — the dangers of reckless absolutism have never been more obvious.

Internal exile and forced labor camps existed in Russia before the 1917 revolution, but the practice of rounding up citizens by category was supercharged in the 1930s under Joseph Stalin. The operating ethos of Stalin’s rule was: Give us the body and we will produce the case against it. Writing about The Gulag Archipelago in the March 1974 edition of the New York Review, the historian and diplomat George F. Kennan noted that the inhuman excesses of Stalin’s time, “… gained an inner momentum of its own, and ended by carrying relentlessly along in its tentacles all those connected with it: prisoners, guards, investigators, torturers, and executioners alike.”

The Big Green Tent by Ludmila Ulitskaya, one of contemporary Russia’s most famous novelists and playwrights, begins after Stalin’s death in 1953, in the heart of the period Solzhenitsyn documented; in fact, a Samizdat copy of The Gulag Archipelago features in the novel. Published in 2010, with translation by Polly Gannon, The Big Green Tent is a Russian epic in the tradition of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, chock-full of wisdom about the frailty of the human condition and the coercive effect of unchecked power.

Like the czars before him, Stalin ruled with such an iron hand for so long that many refused to believe the news of his death or speak of it out of fear. Years of conditioning, of hiding and holding back one’s opinions, of keeping the smallest possible profile and going unnoticed were a way to survive.

“The police are a vine,” Ulitskaya writes, “with tendrils and runners reaching into every part of the government.” In the face of vast bureaucracies of forced compliance, fear and caution are entirely justified, but extract a terrible toll on every individual who attempts to live with integrity.

The novel follows three primary characters, and dozens of others, over the course of 30 chapters. Ilya, Sanya, and Mikha meet as young students and form an unbreakable bond of friendship that survives periods of separation. They refer to themselves as the Trianon. Ilya is drawn to photography (and later Samizdat), Sanya to music, and Mikha to poetry. They fall under the sway of Victor Yulievich, a charismatic literature teacher who lost an arm in the war. Victor harbors no illusions about the Soviet government; he makes a point of injecting his lessons with a “strategy of awakening.”

Another major influence on the boys is Sanya’s grandmother, Anna Alexandrovna, a wise and cultured advisor with aristocratic lineage and many social connections. “No matter how you look at it,” she tells the boys, “the history of Russia has been rotten, but those times were not the worst imaginable. There was a place for nobility, and dignity, and a sense of honor.”

Most of the characters in this work of realism know someone who served time in the camps or lost someone to them, and many view Stalin’s death as a gift. The boys share a mutual hatred of Stalinism as strong as their love of literature.

But even with the death of Stalin, this is a society ruled by fear and suspicion, and as the boys become men they cannot escape this fact, Ilya and Mikha in particular. It’s madness to be a free thinker, to sign petitions, to rebel in ways large and small. As Mikha says to his wife, “How strange our Soviet — or maybe Russian — life is: you never know who will denounce you, report you to the authorities, or who will help you out; or how quickly those roles might reverse.”

In the Acknowledgements, Ulitskaya expresses her gratitude for “the dear departed who have served as the inspiration for my characters, the innocents who stumbled into the meat grinder of their time, those who survived, and those who were maimed; the witnesses, the heroes, the victims.”

This review originally appeared in the California Review of Books.

Premier Events

Fri, Jan 23

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Divine I Am Retreat

Sun, Jan 25

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

18th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap

Thu, Jan 22

3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Grand Opening at Ghirardelli Chocolate & Ice Cream

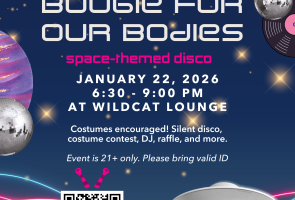

Thu, Jan 22

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Boogie for our Bodies

Sat, Jan 24

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Sweet Home Santa Barbara-The Doublewide Kings

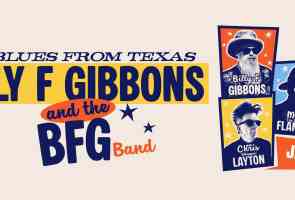

Sat, Jan 24

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Billy F Gibbons and the BFG Band

Sun, Jan 25

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

18th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap

Mon, Jan 26

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Lucinda Lane Returns to SOhO

Tue, Jan 27

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

CWC Docs: Pistachio Wars

Wed, Jan 28

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

The Astonishing Tale of Ludmilla and Thad Welch

Fri, Jan 30

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Friday Night Supper Club at Tyler x Lieu Dit

Fri, Jan 30

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Folk Orchestra of Santa Barbara Medieval Concert – El Presidio Chapel

Fri, Jan 23 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Divine I Am Retreat

Sun, Jan 25 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

18th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap

Thu, Jan 22 3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Grand Opening at Ghirardelli Chocolate & Ice Cream

Thu, Jan 22 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Boogie for our Bodies

Sat, Jan 24 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Sweet Home Santa Barbara-The Doublewide Kings

Sat, Jan 24 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Billy F Gibbons and the BFG Band

Sun, Jan 25 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

18th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap

Mon, Jan 26 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Lucinda Lane Returns to SOhO

Tue, Jan 27 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

CWC Docs: Pistachio Wars

Wed, Jan 28 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

The Astonishing Tale of Ludmilla and Thad Welch

Fri, Jan 30 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Friday Night Supper Club at Tyler x Lieu Dit

Fri, Jan 30 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.