The first time I interviewed multifaceted music legend Don Was, we sat down in his old house in the Hollywood Hills, on the “Valley” side of Mulholland, formerly the domicile of schlockmeister auteur Russ — Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! — Myers. The timing of the interview was to promote one of his few actual solo albums, the jazz-flavored sounds of Orquestra Was’s Forever’s a Long, Long Time, and a cover story for Jazziz magazine.

But the residual influence of low- and higher-culture celebrity on the property was a bit distracting, compounded with the arrival of Richie Sambora and Willie Nelson after our interview. They were in and around the house as part of Was’s other illustrious persona, as favored producer for them and the likes of the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Wayne Shorter, Bonnie Raitt … the list goes on.

Forward to now, and Was is certifiably an important reckoning force in the music world — if not as much of a household name as he should be. The bassist and all-around musician who started out in the quirky jewel of a band called Was (Not Was) (with David Weiss as the “non-Was” factor) has now been the head of the venerable Blue Note Records for 13 years and has built up an epic résumé as a producer, artist, facilitator, and enlightened music industry “suit” (sans the suit).

News that Was’s new project, the Pan-Detroit Ensemble, would be stopping at the Lobero Theatre on September 25 alerted many to one of the year’s most significant — if a bit off the radar — local shows of the year. Amid his other duties, Was assembled a limber aggregate of players from his original hometown of Detroit — including saxophonist Dave McMurray, keyboardist Luis Resto, and vocalist Steffanie Christi’an — and cooked up a suitably eclectic songbook, from Was (Not Was) through Grateful Dead goods, soul/funk jams, and even jazz titan Henry Threadgill.

I checked in with the ever-quotable Was for an update on his musical life very much in progress.

I was trying to think back to times you have played Santa Barbara. I remember the Wolf Brothers, with Bob Weir, show at the Arlington several years ago. I know it must all be a blur by now….

A “blur” is putting it mildly. Ha. I definitely remember the Weir/Wolf Bros. show at the Arlington though. It was a very special one — our third show ever. It had been a struggle to reconcile the way I approached those songs with the way Phil Lesh played ’em. Sometime during the first set, I realized that the most Grateful Dead–like way to play these songs was to not attempt to be “Karaoke Phil” but to find my own way into them. Onstage in Santa Barbara, I suddenly began to identify my place in the fabric of this music.

And this is also the hometown of Charles Lloyd. Was that a significant signing when you invited him to join — or rejoin — the Blue Note roster?

Signing Charles was a significant event in the Blue Note story and a huge moment in my life, because I’d been a fan of his since 1967. I have more Charles Lloyd albums in my collection than those of any other artist. Getting to know him, watching him in the studio, and helping to get his music out into the world has been an awesome, inspiring experience.

Everyone at the label loves him so much. It was incredibly gratifying to see him win those unprecedented four awards in the DownBeat Critics Poll this year: Album of the Year, Artist of the Year, Tenor Saxophonist of the Year, and induction into their Hall of Fame. He’s 86, playing and composing in peak form and touring like a 20-year-old. Charles is one of the most gifted artists of our time, and I hope that everyone in Santa Barbara is proud to be his neighbor.

The Pan-Detroit Ensemble sounds like a great project, and one that pays respects to the environment you came out of. Can you give me a thumbnail history of how the project came about, and any guiding concepts behind it?

A couple of years ago, our dear friend Terence Blanchard invited me to put together a band and perform at one of the jazz concerts he was curating for the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Having worked with all of my heroes — from Charles and Wayne Shorter to Bob Dylan, the Stones, Willie Nelson, and Brian Wilson — it was daunting to grapple with where I fit as an artist today and whether there was even a point to having a band while giants like that still roam the Earth.

But I remembered the advice that I’ve often dispensed to artists as a producer or label head: The thing that makes you different from everyone else is your superpower, so emphasize that.

Brilliant as my heroes are, they didn’t grow up in Detroit in the 1950s and ’60s, you know? The Stooges didn’t play at their high school, they didn’t ride a bus downtown to see the Motown Revue play to a half full matinee at the Fox Theater, George Clinton didn’t play a sock hop at their junior high school, they didn’t drop acid and go to an MC5 show at the Grande Ballroom, and they didn’t grow up in the middle of the cultural jambalaya that characterized Detroit in that period.

So I decided to go back home, get together with some other like-minded musicians, and let our Detroit Freak Flag fly. When we got together to rehearse, it was clear in the first 10 minutes that there was something special going on with this combination of cats, and we decided to book a whole tour around Terence’s show. Now we’re launching a second leg on the West Coast to be followed by Asia in the spring and Europe next summer.

Does the band really come alive in the live setting? Does improvisation and spontaneity work in the live-show recipe?

Absolutely. They’re all quite accomplished jazz players and generous musical conversationalists. And, in the same breath, they can play a raw, Detroit-style R&B groove. There is a structure to the songs, but part of that structure calls for fearless improvisation where the only rule is that you can’t play what you’ve previously played.

You’ve got to get back to a beginner’s mind and approach the music with no preconceptions. So, every night is a whole new adventure, and every show is different. We have a ball playing together, and, based on the response to our first tour, the audience can pick up on that spirit and elevate along with us.

Detroit has been such a powerful musical hub in the American music scene, in many and varied ways. Can you say what makes it such a special place, and did its pulse and attitude leave a bold mark on you from youth?

After World War II, folks came to Detroit from all over the world and brought their cultures with them. It was a vibrant global center. Before long, the disparate styles of music started to blend into something new and unique to the city. On top of that, when you have a one-industry town, everybody is in the same economic boat. There’s no point in putting on any airs to impress folks, because we’re all at the mercy of the auto business.

That results in a very unpretentious, honest population and is manifested in the music that comes from there. John Lee Hooker is kind of the embodiment of Detroit music: so raw and unpolished that it’s on the verge of falling apart at any moment, but loaded with soul, truth, and a deep groove that refuses to take any prisoners. Everyone in the Pan-Detroit Ensemble is a product of that ethos. They all still live in town. I’ve got a place there too and try to spend as much time in the middle of that milieu as I can.

It’s interesting that this group has the potential to reach across supposed demographic borderlines, from jazz to R&B and the jam-band universe. Is that one of the goals, in fact, to appeal to a wide berth of ears?

I think that the goal is to reach beyond the superficial divisions that separate us — both societal and genre-related — and to address the emotional commonality that all humans share. On the last tour, we played jazz clubs, rock ’n’ roll clubs, Delfest (which is a bluegrass festival near West Virginia), and to 2,000 seated folks at the rather staid Detroit Symphony Hall. We got the same enthusiastic response everywhere.

Everybody, on all ends of the spectrum, is traumatized by the world today and needs to remember that we’re all in this together. This band is here to gently remind them of that, to spread a little joy and to make everybody want to get up and dance.

The band’s songbook represents a diverse gathering of tunes, originals, and various corners of American music. An open-mindedness in terms of genre, era, and milieu. Is the art of curating a set list part of what makes this project tick?

Genres are great for organizing record stores and helping radio stations target demographic groups for advertisers, but I don’t think musicians think about it much. I don’t know any musicians who say, “Hmmm … I think I’ll play a blues lick here, and then in two bars, I’ll play a country lick and then throw in a jazz run.” You just play what you feel. The desire to transcend boundaries and make some kind of uncategorizable music is a virtue. This band approaches a Henry Threadgill song the same way we approach a Cameo song — a good song invites you in, regardless of genre.

Kudos for including Henry Threadgill in the mix — one of my heroes and someone so respected in jazz and new music circles but too little-known in more general public or other musical neighborhoods. Are you a Threadgill fan by nature, and do you like the idea of turning on new listeners to his music — a process similar to what you do at Blue Note?

Henry Threadgill is the living embodiment of what we’re talking about — for the last 50-some years, he’s been upsetting the apple cart, defying expectations, and disrupting the herd. Ha. He’s been a heroic figure to me going back to his (Chicago-based) AACM days — that whole scene was very influential in Detroit. It’s an honor to turn new listeners on to him, but there’s no ulterior motive for us playing “I Can’t Wait Till I Get Home” every night beyond the fact that it’s a great fucking song with many different rooms to explore.

You are now 13 years into your much-accoladed role as the head of Blue Note Records, ushering in a literal new chapter in its storied history. Is this still something of a dream job for you, and do you have ideas of where it has been and where it is going?

It’s totally a dream job. I feel a tremendous responsibility to uphold the label’s legacy by making sure that our new music reflects the ethos of our founders and that our catalog is available to everyone.

When I was initially hired, it seemed that the first task was to try and figure out why music that Blue Note released 50 or 60 years ago still remains relevant and vital. In every era, Blue Note signed artists who had mastered the fundamentals of the music that came before them but then applied that knowledge to create something brand-new. That second part is really important — it’s not enough for the artists to simply curate a museum of yesterday’s jazz — they’ve got to continue pushing the envelope and going where no man has gone before.

So that’s where Blue Note’s been, and that’s where it’s gonna continue to go.

Was (Not Was) was really a unique band, a cool and slightly crazed amalgam of genres, with gonzo humor folded in (as in “I Feel Better than James Brown”). Do you look back on a path leading from that experimental project to a life working with rock and jazz luminaries with a kind of wonderment, a kind of “How did I get here?” sensation? Or did you always envision working your way into various byways of music on a large scale?

There isn’t a day that goes by without several moments of wonderment and gratitude for the life I’ve been allowed to lead. It’s weird: All of my wildest dreams and ambitions kinda were realized by the time I was 40. After that, the only long-range goal was to be part of creating some music that would enrich the lives of listeners for decades to come — in the same way that my life was touched and guided by the music of others. It seems like a worthwhile calling and has been the source of some incredible high adventure along the way.

How do you see the Pan-Detroit Ensemble evolving? Will this be one of the projects on your list going forward?

We’re still at the point where we improve exponentially with each show, and I see no reason for that to taper off. I wish we had a time machine, because I’m dying to see where this road is gonna lead. What I know for sure is that this band is going to be part of my life until I drop. We have so much fun playing together.

If you come to the Lobero, I guarantee you’ll walk out feeling better than you did walking in.

Don Was and the Pan-Detroit Ensemble perform on Wednesday, September 25, at 7:30 p.m. at the Lobero Theatre (33 E. Canon Perdido St). See lobero.org.

Premier Events

Fri, Jan 09

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Intention Setting & Candle Making Workshop

Sun, Jan 11

3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mega Babka Bake

Fri, Jan 23

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Divine I Am Retreat

Fri, Jan 09

8:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Herman’s Hermits’ Peter Noone: A Benefit Concert for Notes For Notes

Fri, Jan 09

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ancestral Materials & Modernism

Fri, Jan 09

6:00 PM

Montecito

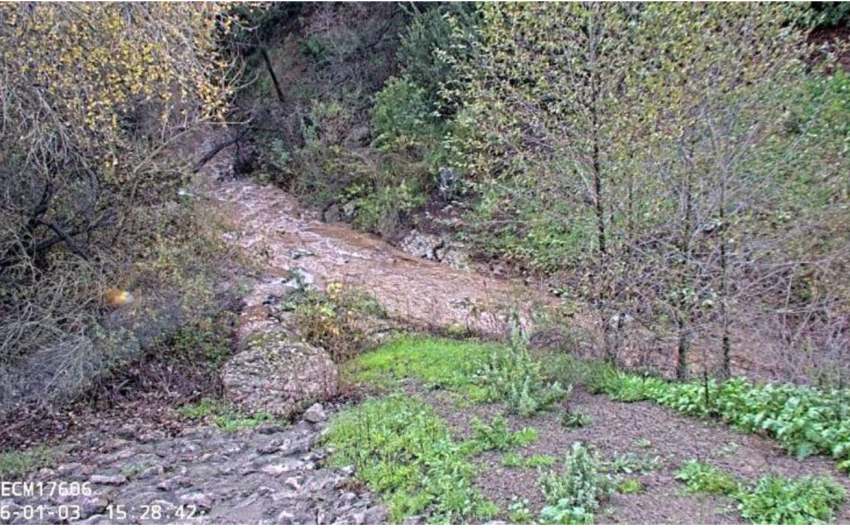

Raising Our Light – 1/9 Debris Flow Remembrance

Fri, Jan 09

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Barrel Room Sessions ~ Will Breman 1.9.26

Sat, Jan 10

9:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Rose Pruning Day | Mission Historical Park

Sat, Jan 10

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Konrad Kono – Live in Concert

Sat, Jan 10

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SB Improv: The Great Cornadoes Bake-Off

Mon, Jan 12

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Hot Off the Press: Junk Journal

Tue, Jan 13

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

✨ First Singles Social of 2026 | Open to All Ages 21+

Fri, Jan 16

9:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Eric Hutchinson at SOhO

Fri, Jan 09 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Intention Setting & Candle Making Workshop

Sun, Jan 11 3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mega Babka Bake

Fri, Jan 23 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Divine I Am Retreat

Fri, Jan 09 8:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Herman’s Hermits’ Peter Noone: A Benefit Concert for Notes For Notes

Fri, Jan 09 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Ancestral Materials & Modernism

Fri, Jan 09 6:00 PM

Montecito

Raising Our Light – 1/9 Debris Flow Remembrance

Fri, Jan 09 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Barrel Room Sessions ~ Will Breman 1.9.26

Sat, Jan 10 9:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Rose Pruning Day | Mission Historical Park

Sat, Jan 10 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Konrad Kono – Live in Concert

Sat, Jan 10 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SB Improv: The Great Cornadoes Bake-Off

Mon, Jan 12 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Hot Off the Press: Junk Journal

Tue, Jan 13 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

✨ First Singles Social of 2026 | Open to All Ages 21+

Fri, Jan 16 9:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.