Shelby Property Owners Sue City of Goleta over Right to Pursue Builder’s Remedy Housing Project

Couvillion Family Proposes 56 Single-Family Residences on Ag Land Next Door to Glen Annie Golf Course

After Glynne Couvillion bought some run-down orchards at 7400 Cathedral Oaks Road, he took to calling it “Resurrection Ranch.” He hoped to grow thriving groves of avocados and persisted through three separate plantings, all of which developed root rot. So Couvillion reconsidered growing homes. After all, the land was zoned residential when he bought it in 1978.

Although a drought and a water moratorium put the housing project on pause, he did receive a vested tract map for the land, now known as the Shelby property. About the time that abundant rains presaged an end to the water moratorium, California began to crack down on its umbrella of rules called the Housing Element. Any jurisdiction that failed to file the swarm of legislation and documents on time was vulnerable to the builder’s remedy, including the City of Goleta in 2023.

Seizing the moment, Couvillion, who is today a 91-year-old retired eye surgeon, and his project team filed a builder’s remedy application for 56 single-family homes, of which 13 would be deed-restricted, lower-income homes. The City of Goleta rejected the application, however. Despite the talks between the parties that year, since this January the issue has been at Santa Barbara Superior Court, where Judge Thomas Anderle will have the pleasure of untangling the complex issues surrounding the Housing Accountability Act and the builder’s remedy in this case.

A Complicated History

Shaped like a stubby thumbs-up, the 12-acre Shelby property juts northward along the City of Goleta’s western boundaries, across the street from Dos Pueblos High School and bordered on three sides by Santa Barbara County. Owned by the Couvillion family for the past 45 years, the land that was once part of W.W. Hollister’s fabled Glen Annie Ranch has a complicated zoning history — Santa Barbara County–zoned residential since the 1950s and rezoned agricultural during the water and development wars of the ’70s and ’80s when the county population nearly doubled.

Glen Annie Golf Club moved in next door in 1994, and Cathedral Oaks Road was completed in 1997 across a Shelby easement. The City of Goleta formed in 2002, the Goodland Coalition was born in 2011, and five back-to-back years of drought started in 2012.

What also occurred during 2012, aside from the reelection of Barack Obama in November, was the passage of Measure G by 71 percent of Goleta voters. Backed by the conservation-minded nonprofit the Goodland Coalition, Measure G set out to preserve Bishop Ranch — the big carpet of green just above the Glen Annie/Storke Road highway exit — and mandated that any proposed subdivision of ag lands larger than 10 acres must go to a vote of the people.

As they say, timing is everything.

The Couvillions received the vested tract map in 2011, before Measure G passed. While Shelby avoided the ballot, it would still need City Council’s approval to rezone from agriculture to residential. When Santa Barbara County considered doing just that for Glen Annie Golf Club, the current Goleta council was seriously opposed. The county — stuck in the same hard place as the city over the state-mandated Housing Element, which compels more zoning for homes — changed the zoning of the golf course from agriculture to residential in April 2024.

What was likely a year of anxiety for the city was a ray of sunlight for the Couvillions. During much of 2023, Goleta’s Housing Element was between adoption and rezoning as it attempted certification by the state. The boon for the Couvillions is the provision of builder’s remedy that erases the need to rezone to residential zoning.

Builder’s Remedy: Headache or Heaven-Sent?

For citizens interested in very careful, i.e., painfully slow, planning procedures, the builders remedy was a wallop upside the head.

Though enacted 30 years ago, it became a contender in 2022 when Santa Monica found itself in protracted Housing Element arguments and missed the certification deadline, as did most Southern California jurisdictions. Developers swooped in, claiming the right to build 15-story apartment buildings regardless of Santa Monica’s planning rules but with the required 20 percent affordable units (or 100 percent moderate-income homes).

Those threatened skyscrapers turned out to be bargaining chips in the developers’ fights with the city, but since then, builders remedy projects have snaked through planning departments in desirable areas, landing in the courts for interpretation of the vague statutes.

The tract map for the Shelby property laid out 60 single-family homes. The Couvillions’ attorney, Beth Collins of Brownstein Hyatt, showed the Independent the property on Wednesday. Because of El Encanto Creek on the west side, she explained, four of the mapped homes were removed to honor the city’s new creek setbacks.

Most of the homes are small, about 1,850 square feet. Exactly how the 13 deed-restricted, lower-income homes will be included has yet to be worked out, Collins said, but they might be a mix of single-family homes and accessory dwelling units, aka granny flats.

Having leapt the low-income requirement of builder’s remedy with room to spare, the Couvillions’ application asked the city to retain their right to build housing outside of Measure G’s vote requirement. They also invoked Senate Bill 330 (SB 330), a provision of the Housing Accountability Act, that requires, among other things, the city to process the completed preliminary application submitted on November 28, 2023, hold no more than five public hearings, and adhere to the rules in place at that time.

The Couvillions had actually submitted the application twice, once in March and once in November. According to a letter from City Attorney Megan Garibaldi, Goleta could not accept the Shelby application because the Couvillions wanted to retain their vested map of 2011. They could not use a vested right of 2011 and also use the builder’s remedy for events of 2023. It was one or the other, Garibaldi wrote, but the city was willing to talk it over.

Those talks left both sides far apart. Dr. Couvillion stated, “This past year we have worked earnestly with the city to seek cooperation to use this property for higher density, to help Goleta build much needed workforce housing. Regrettably, we have not been successful, all the while incompatible densities are being proposed next to older single-family neighborhoods citywide.”

Because the matter is in litigation, city planning chief Peter Imhof said they could not discuss the project. According to the legal pleadings, talks went on all year. At the 11th hour, a week before the council would meet to adopt the Housing Element, the project team submitted their SB330 application a second time. They got the same result.

Time Will Tell

Other timing issues may come up in Anderle’s court: The largest might be whether Measure G applies to an SB330 application filed in 2023 or if the vested tract map in 2011 prevails. Another novel conundrum was raised by the city attorney of whether builder’s remedy arises upon project approval or project application, stating that the city believed it was upon approval.

Then there’s the golf course zoning. Glen Annie Golf surrounds much of Shelby on three sides, creating a “resource preservation” zone, the city claimed, which protected Shelby from being used for housing, according to one provision of the Housing Accountability Act. However, five months after the Couvillion application was submitted, the county switched the golf course zoning to residential.

And will Shelby benefit from the plentiful rains that triggered in January the lifting of Goleta Water District’s moratorium on new hook-ups? As much as 150 acre-feet of new water is available per year — as long as there’s no drought, Bob Wignot pointed out. Wignot helped create the Goodland Coalition, promulgator of Measure G.

“It doesn’t make sense to say ‘build now, cut back later’ when we know there will be another drought,” Wignot said. “How does that work?”

Wignot thought Measure G should be observed and that the project should go to Goleta voters. He noted the need for affordable and workforce housing, not the market-rate housing the majority of Shelby will become. And he asked how the traffic issues at Glen Annie and Cathedral Oaks during rush hour for residents and Dos Pueblos High School will be resolved.

These same traffic and water issues will come home to roost for the developers, nonprofits, and school district hoping to build hundreds of homes atop 100 acres of Glen Annie Golf Club, which remains in the County of Santa Barbara. However, litigation has begun with its neighbor to the north, Glen Annie Organics, which argues that residences mean herbicides and fertilizers, not to mention roaming pets and their “potential bacterial and fecal coliform contamination” of organic fields.

Recently added to the chorus of opponents is a petition organized by Keep Goleta the Good Land at ThePetitionSite.com. “Tell the politicians and the developers to leave Glen Annie Golf Course the way it is!” petitioner Tom Modugno wrote. It’s gathered 457 signers of its 1,000-supporters goal.

According to Collins, it all comes down to housing. The single-family homes and lower-income homes the Couvillions propose will be a benefit for Goleta, which lacks new homes for sale.

“So many of my colleagues commute from Ventura or Lompoc,” she said. “We really need housing, especially affordable housing.”

Premier Events

Fri, Jan 31

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Wed, Jan 22

5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Talk: “Raising Liberated Black Youth”

Sun, Jan 26

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara,

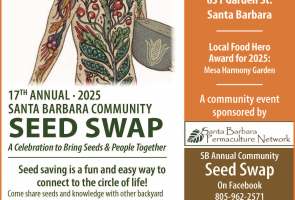

17th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap 2025

Tue, Jan 28

5:00 PM

Zoom

Fire Safety Community Zoom Meeting

Thu, Jan 30

8:00 PM

Solvang

Lucinda Lane Album-Release Show, at Lost Chord Guitars

Fri, Jan 31

9:00 AM

Goleta

AARP FREE TAX PREPARATION

Fri, Jan 31

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Sat, Feb 08

10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Paseo Nuevo Kids Club

Sat, Feb 08

12:30 PM

Solvang

Garagiste Wine Festival

Tue, Feb 11

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Timothée Chalamet

Thu, Feb 13

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Adrien Brody and Guy Pierce

Fri, Jan 31 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Wed, Jan 22 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Talk: “Raising Liberated Black Youth”

Sun, Jan 26 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara,

17th Annual Santa Barbara Community Seed Swap 2025

Tue, Jan 28 5:00 PM

Zoom

Fire Safety Community Zoom Meeting

Thu, Jan 30 8:00 PM

Solvang

Lucinda Lane Album-Release Show, at Lost Chord Guitars

Fri, Jan 31 9:00 AM

Goleta

AARP FREE TAX PREPARATION

Fri, Jan 31 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Artist Talk at Art & Soul on State Street

Sat, Feb 08 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Paseo Nuevo Kids Club

Sat, Feb 08 12:30 PM

Solvang

Garagiste Wine Festival

Tue, Feb 11 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SBIFF – Tribute to Timothée Chalamet

Thu, Feb 13 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.