When dusk falls, the daytime birds find a well-hidden roosting site, perhaps deep within a thicket, for at night they are at their most vulnerable. They remain motionless and silent until the morning if they survive the attentions of the night hunters. It must be a powerful urge, then, that sends hundreds of millions of birds into the night sky to migrate south every fall, more powerful than their natural fear of the night. Many of these birds are juveniles, striking out on their own, into the unknown, on their first great journey.

I’ve often wondered what it must be like for these youngsters, obeying the urge to launch alone into the night sky. I imagine they feel something akin to terror. I recently had my thinking changed, however, when I read new research that suggests migration is more of a communal affair, where different species form “migrating communities.”

Joely DeSimone, researcher at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, thought that with so many birds in the air together, there must be some kind of interaction going on. It’s well-known that birds call frequently at night during migration. Indeed, if you step outside at night during the next couple of months, you might hear the faint calls of birds passing overhead.

DeSimone had the idea of looking at data from banding stations, where birds are caught in nets, measured, cataloged, fitted with a band, and quickly set free. Banding stations are located at known gathering sites for migrating birds, so it made sense to see if there was data to show that migrating birds were moving together.

The researchers gathered more than half a million records from five stations across eastern North America. After much statistical analysis, lo and behold, the data proved that birds have their own “interspecies social networks.” These networks held true across all the banding stations.

DeSimone had surmised that birds with similar dietary needs would avoid one another to cut down on the competition for scarce resources; they were surprised, then, when they discovered the opposite to be true. Nashville warblers and Tennessee warblers, both tiny green-and-yellow birds that have essentially the same diet, often travel together during migration. Another example of interspecies traveling buddies involves the American redstart and magnolia warbler.

The researchers conjecture that one possible benefit that such companionship could bring is that, because of the birds’ similarities, they can help each other discover prime feeding habitat.

Whether these “social networks” are formed at night as the birds are on the move, or when the birds have landed and are actively seeking food, is still unknown. I’d like to think that it’s the former, and that the birds have some company as they journey in darkness, especially for the youngsters who are striking out for the first time.

The next Santa Barbara Audubon Society program will be Why Are Some Birds So Colorful? The Evolution of Avian Ornamentation, presented by Steven Gaulin. Gaulin is a Professor of Anthropology at UCSB and an avid birder. The talk will take place on Tuesday, September 17, at 7 p.m. at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History’s Fleischmann Auditorium (2559 Puesta del Sol). It will focus on why flamboyant colors and traits are especially conspicuous in many species of birds and the connection of such ornamentation to sexual selection. The event is free and is open to the general public.

Hugh Ranson is a member of Santa Barbara Audubon Society, a nonprofit organization that protects area birdlife and habitat and connects people with birds through education, conservation, and science. For more information, see santabarbaraaudubon.org.

Premier Events

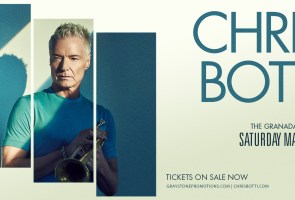

Sat, Mar 29 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Chris Botti in Concert

Sun, Apr 06 11:30 AM

Santa Barbara, CA

Gun Violence Prevention Forum with Asm. Gregg Hart

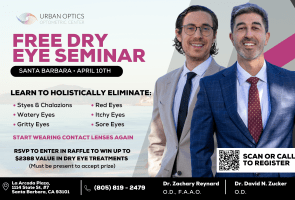

Thu, Apr 10 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Free Dry Eye Seminar w/ Dr. Zucker & Dr. Reynard

Fri, May 23 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Songbird: The Singular Tribute to Barbra Streisand

Thu, Mar 27 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Live Music Supporting Direct Relief

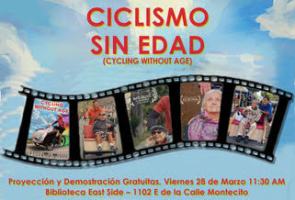

Fri, Mar 28 11:30 AM

Santa Barbara

Encore Screening: Cycling Without Age

Fri, Mar 28 5:30 PM

Santa Barbara

The Happiness Habit (2 for 1)

Fri, Mar 28 7:00 PM

Ojai

Evening of Sacred Song & Mantra with Donna De Lory

Sat, Mar 29 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

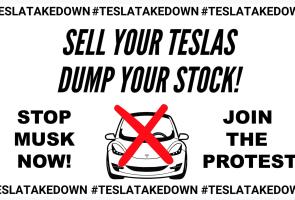

Global Tesla Takedown

Sat, Mar 29 10:30 AM

Santa Barbara

Children’s Resource Fair

Sat, Mar 29 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

National Vietnam War Veterans Day Celebration

Sat, Mar 29 1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

3rd Annual Canned Food Drive and Community Event

Sat, Mar 29 3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

MCASB Presents Los Tranquilos Mini Concert

Sat, Mar 29 5:30 PM

Santa Barbra

You must be logged in to post a comment.