In Santa Barbara, Oil and Rain Don’t Mix

Slow Action to Stop a Slow Seep Has Cost the County Plenty

Without a peep of discussion, the county supervisors approved an additional $155,000 to build a concrete contraption on the banks of Toro Canyon Creek in order to contain a slow-moving oil seep that’s been festering since oil was first drilled there in the 1880s. The lack of discussion is not surprising; the subjects — oil, water and Toro Creek — are all painful ones for the county government.

In 2023, the county’s own District Attorney filed misdemeanor criminal negligence charges against its own county administrator because of how slowly the public works department had respond to the oozing oil seep, an industrial byproduct of a long-abandoned well. The county had known about the problem since 2018, but its administration seemed in a torpor, unable to respond to the looming problem. Showing up in court to plead guilty to misdemeanor counts of criminal negligence were County Executive Officer Mona Miyasato and Supervisor Steve Lavagnino

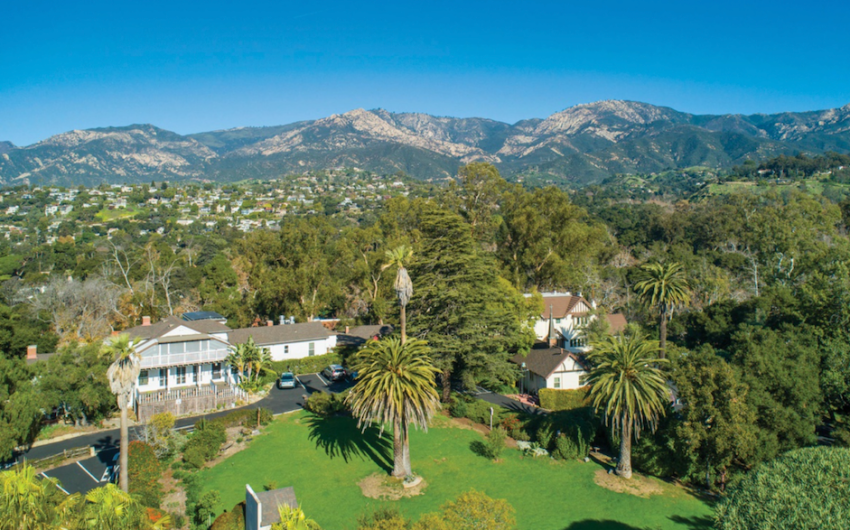

When the torrential rains of January 2019 pelted the county, it combined with that seeping oil, sending 600 gallons of oil-infested water down the creek to the ocean. Along the way, several amphibious critters were killed and others required rehabilitation.

It would not be until 2021 that the county began cleanup efforts in earnest. Before the administrator’s guilty plea, the county spent $1 million on private attorneys to resist — unsuccessfully — the DA’s demands for public documents. Making matters more painful, responsibility for the creek cleanup was foisted upon the county by the Regional Water Quality Control Board and the EPA. State and federal funding for the county’s costs dried up in 2019, the same year the floods came.

Then the heavy rains that bombarded the county early this year so inundated Toro Canyon Creek that the nearby soil was saturated with the runoff six feet deep. To build the concrete storage and diversion box, engineers will have to dig six feet down to stabilize the soil. That’s what the $155,000 will pay for. The oil company that drilled the original mine from which the oil has seeped has long since gone out of business. That brings the cost to the county’s general fund for this mess to date to $5.4 million.