The Isley Brothers story is a great American musical epic, whose dimensions have influenced the evolution of R&B and rock ’n’ roll over the course of six-plus decades. A brief list of greatest hits tells a story on its own: “Shout,” “Twist and Shout,” “It’s Your Thing,” “That Lady,” “Between the Sheets,” and on and on. Still, remarkably, the story also exemplifies a case of “hiding in very plain sight,” in terms of a full appreciation of the band’s output as well as a case study in the notorious and ever-valid disrespect for the huge impact of Black culture — especially in music.

For a fuller, deeper picture of the Isley tale, proceed to Darrell M. McNeill’s fascinating new book The Isley Brothers’ 3 + 3, part of the vast and expanding series of compact books focused on specific albums under the rubric of Bloomsbury’s 33-1/3 series. Taking off from their classic and career-fueling 1973 album 3 + 3 (named for the double sets of Isley siblings), McNeill provides a sweeping historical overview of one of America’s greatest and longest-running bands, touching on influences, changes in the music industry and racial/cultural observations along the way.

McNeill, out of Brooklyn but now based in Santa Barbara, has a hyphenated résumé, as musician/producer/music journalist who is also director of operations for the Black Rock Coalition (BRC) and, locally, serves as cofounder/director of the Santa Barbara Black Culture House and as chair on the Arts Advisory Committee.

Remarkably, the Isley Brothers story, dating back to the mid-’50s from their familial hearth of a gospel music family just outside of Cincinnati, continues, nearly seven decades deep. They played in the area as recently as 2018, at the Chumash Casino, with remaining primary voices at its center — supple lead singer Ronald and master guitarist brother Ernie. Just two years ago, the Brothers released a new single version of the 1975 hit “Make Me Say It Again,” with a cameo from Beyoncé, paying respects to legends who paved the way for many.

For a solid primer in all things Isley, proceed to McNeill’s compact but substantial book. Here are four things I learned from 3 + 3:

Respect Is Due, Along the Black-White Music Divide

McNeill pays a fair amount of attention to the ironic disparity between the Isley Brothers’ prolific and influential musical output, and the disproportionate credit granted by the critical and industry powers that be. It’s a running theme and polemic, frequently revisited through the book and laid out plainly in the introduction:

“The Isley Brothers are, indisputably, America’s longest-tenured, most venerable, active rock and roll group. Not R&B, nor funk, nor soul group. Rock and roll group.

“This is not hyperbole. This is not opinion. This is an uncontestable fact. Let it be said again. Loudly. For the haters, the cynics, the hard-headed, the tone deaf, and so all the folks in the back and up in the cheap seats can hear: The Isley Brothers are, indisputably, America’s longest-tenured, most venerable, active ROCK AND ROLL GROUP. Not R&B, nor funk, nor soul group. Again: ROCK AND ROLL GROUP.

“Deal with it.

“Music and culture do not manifest in a societal vacuum, no matter how angrily we demand it to be so. That fiction leads down a road of misguided denial of the creators’ experiences, the audiences they touch, and the gravitas of their work. This book, about music, is equally about culture, society, politics, and race, and how these factors shape the music and how it is received (or not).”

Near the end of the book, the author exercises righteous indignation over a long-recognized truism in pop music history and fate. “Countless acts like Wynonie Harris, Ruth Brown, Muddy Waters, LaVern Baker, Frankie Lymon, et al. all died penniless. Sam Phillips, Elvis’s discoverer, got his million-dollar ‘White man with the Black sound,’ but Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup and Willie Mae ‘Big Mama’ Thornton, whose hits launched Elvis to fame, never had two nickels to rub together between them. This is the rawest nerve in any discourse that neuters the role race plays in rock: the worth of Black contributions, sacrifices, and lack of reparations has been irretrievably obfuscated.”

Isley-Mania and the Beatles Connection

Early on in the saga, shouting got them noticed. After the Brothers scored their first major hit, and a timeless song in the American music canon, with 1959’s upbeat “Shout,” they scored a hit with 1962’s “Twist and Shout,” then picked up and turned into a much larger hit for the fledgling band called the Beatles. In a documentary on the song’s co-writer Burt Berns, Sir Paul McCartney effused, “The Isleys’ version just blew our minds. This was a great song to perform… I told Ernie, ‘If it were not for the Isley Brothers, the Beatles would still be in Liverpool.”

Letting Jimi Come Over

The Isley Brothers provided a critical early gig for guitar visionary Jimi Hendrix. The young firebrand showed up at the Isley home in Teaneck, New Jersey, sans guitar, which he had pawned. McNeill writes, “Hendrix was a pure gentleman in the Isley house, [the Isley’s mother[ Sallye taking to him like another son. He grew close to the younger boys, watching TV together, even catching the world-shattering Beatles debut on Ed Sullivan with the family. There was vague foreboding as the Isleys saw rock’s future laid bare: The Beatles’ popularity signaled a change of the guard, galvanizing a stampede of aspirant (White) rockers into guitar shops — a genre that never treated Black artists fairly would only get worse now….

“Hendrix on the road was a different beast — he was every bit the wild man he was hired to be: combustible solos, wild theatrics, and outrageous style. He upstaged the band, and, at times, the Isleys themselves. The group were adherents of R&B tradition: drill team choreography, precision performance, pristine grooming. This regimen was anathema to Hendrix — he wore bright scarves and bracelets in defiance of the dress code.”

Hendrix’s guitar work can be heard on the gospel-fired Isley song, “Testify,” but soon enough, he inevitably moved on to develop his own solo mythic musical life as a leader. He left a strong influential imprint on the then very young guitarist Ernie, who has sometimes been praised as the “heir apparent” to Hendrix. Exhibit A, Ernie’s trademark wailing solo on “That Lady.”

On Disco Sucking and Crossover Blues

By the late ’70s, the dance floor of disco was taking over the musical room where much of Black R&B had thrived. The “disco sucks” backlash and the diluting of crossover tactics created tensions for established Black acts, including the Isley Brothers.

McNeill quotes critic Nelson George, who asserted, “Crossover moves only served short term — for veteran Black acts, it actually accelerated the end of their viability in the market: A Black [artist] who crossed over could sell a humongous number of records. And the fact that so few succeeded didn’t stifle the dream. For many Black entertainers, chasing that dream was a fixation, and one that could destroy a career.”

For example, wrote McNeill, “Earth, Wind & Fire, once an apex Pan-Africanist polyglot ensemble steeped in spiritual messaging and jazz foundation, transformed into culturally neutered disco-soul superheroes. Kool & The Gang traded rough Jersey City jazz-funk for polished discotheque sheen. The Commodores’ homespun Tuskegee funk switched up to saccharine pop balladry in service to their one-time front man. Even pinnacle genius Stevie Wonder reigned in his once-vanguard experimentation. The dice roll was: (a) if hardcore fans would follow, (b) if new Black fans would buy in, and (c) if White fans would even care.

“Contrary to rock hubris, disco didn’t ‘die.’ Disco resurfaces cyclically and is resurgent in the 2020s, but as the 1970s waned, it went into the background. This made the Isleys’ next move curious — they not only did a deep dive into disco, they literally doubled down.”

The Isleys busted out the disco ball and grooved on their albums Go All the Way and Winner Takes All. Both scored well on the Billboard charts and at the box office, as Isley music tends to. That was then, in 1980, and the brother saga continues, after the passing of four of the six and despite imbalances in its critical/historical status.

To quote McNeill’s nearly last word on the Isley subject in 3 + 3, “It’s time for the rock music establishment to start paying back the Isleys — and a legion of other Black rock artists — what it owes them: respect. Massive respect. Retroactively. With interest. Forever. The clock starts right now….”

Premier Events

Wed, Dec 31

9:00 PM

Santa barbara

NEW YEAR’S Wildcat Lounge

Wed, Dec 31

6:15 PM

Santa Barbara

NYE 2026 with SB Comedy Hideaway!

Wed, Dec 31

9:00 PM

Santa barbara

NEW YEAR’S Wildcat Lounge

Wed, Dec 31

10:00 PM

Santa Barbara

In Session Between Us: Vol. I NYE x Alcazar

Wed, Dec 31

10:00 PM

Santa Barbara

NYE: Disco Cowgirls & Midnight Cowboys

Thu, Jan 01

7:00 AM

Solvang

Solvang Julefest

Thu, Jan 01

11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Polar Dip 2026

Sat, Jan 03

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

No Simple Highway- SOhO!

Sun, Jan 04

7:00 AM

Solvang

Solvang Julefest

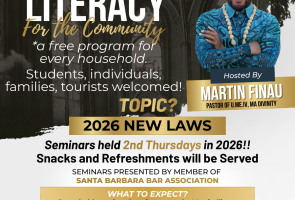

Thu, Jan 08

6:00 PM

Isla Vista

Legal Literacy for the Community

Fri, Jan 09

6:00 PM

Montecito

Raising Our Light – 1/9 Debris Flow Remembrance

Wed, Dec 31 9:00 PM

Santa barbara

NEW YEAR’S Wildcat Lounge

Wed, Dec 31 6:15 PM

Santa Barbara

NYE 2026 with SB Comedy Hideaway!

Wed, Dec 31 9:00 PM

Santa barbara

NEW YEAR’S Wildcat Lounge

Wed, Dec 31 10:00 PM

Santa Barbara

In Session Between Us: Vol. I NYE x Alcazar

Wed, Dec 31 10:00 PM

Santa Barbara

NYE: Disco Cowgirls & Midnight Cowboys

Thu, Jan 01 7:00 AM

Solvang

Solvang Julefest

Thu, Jan 01 11:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara Polar Dip 2026

Sat, Jan 03 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

No Simple Highway- SOhO!

Sun, Jan 04 7:00 AM

Solvang

Solvang Julefest

Thu, Jan 08 6:00 PM

Isla Vista

Legal Literacy for the Community

Fri, Jan 09 6:00 PM

Montecito

You must be logged in to post a comment.