A sacred stretch of ocean along the Central Coast, along with its dedicated stewards, is one step closer to a major victory.

On Thursday morning, amid discussions of various reports and rocket launches, the California Coastal Commission had reason to celebrate. The hearing marked a huge milestone in the designation of the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary, spanning thousands of miles off the coast of Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties.

Federal protection for these waters will safeguard coastal uses and resources and limit disruptions to the region’s ecosystem — a biodiversity hot spot for marine life such as migratory whales and sea turtles — and encompass unique deep-sea topography like the 10-million-year-old Rodriguez Seamount.

The designation will also preserve Indigenous communities’ long-held relationships with the region. It includes some of the earliest recorded human settlements in North America, where Chumash and Salinan bands maintain profound cultural ties.

Though a few kinks — mainly, finalizing the sanctuary’s boundaries — still need to be worked out, the initiative is nearing the finish line.

During the hearing, the Coastal Commission unanimously and enthusiastically endorsed the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) “Consistency Determination.” This means that the proposed sanctuary, along with its draft management plan and proposed regulations, aligns with the California Coastal Management Program’s policies.

In other words: one step closer.

Between Wind and Water

Michael Murray, deputy sanctuary superintendent for NOAA, called the opportunity “historic.” It is not only the first tribally led and managed marine sanctuary, but it will also be the first sanctuary to be established in California in more than 30 years.

And it is decades in the making — originating as a thought bubble among state and local leaders nearly 40 years ago, the sanctuary was officially nominated in 2015, spearheaded by the Northern Chumash Tribal Council.

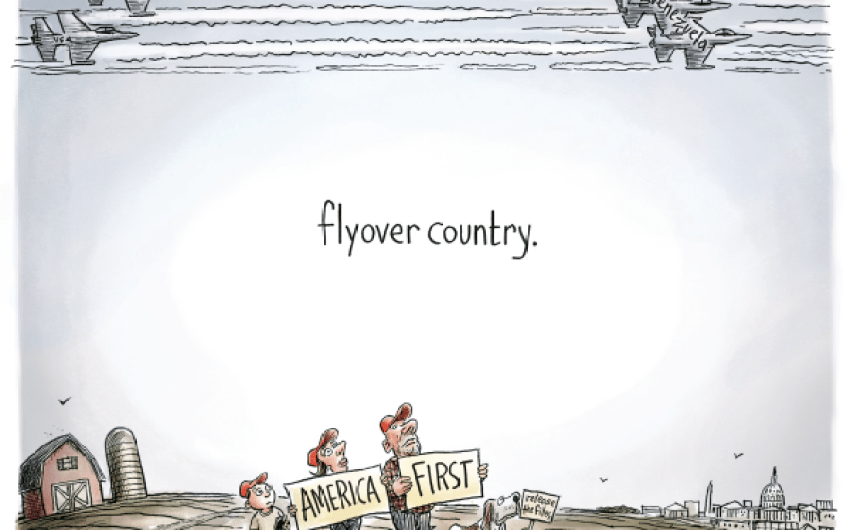

However, no progress is made without a little friction. Namely: plans for developing offshore wind energy within the sanctuary’s proposed boundaries and an unresolved dispute around the sanctuary’s name, as it includes historical areas of both Chumash and Salinan tribes.

[Click to enlarge]The open chunk between the Monterey Bay and the proposed Chumash marine sanctuary can be seen at the map on the left, a space where offshore wind cables could go ashore. At right is the full proposed marine sanctuary. | Credit: Courtesy

As such, five different boundary alternatives of varying shapes and sizes are being considered, with uncertainty shrouding the sanctuary’s final form.

The initial (and largest) boundary alternative would encompass up to 7,600 square miles of ocean and fulfill environmentalists’ dream of connecting the Monterey Bay and Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuaries.

The others would exclude certain areas, with the smallest alternative encompassing only 4,400 miles (which would still make it the second largest marine sanctuary in California).

NOAA’s “preferred alternative” proposes extending the sanctuary boundary along the Gaviota Coast while excluding the northernmost chunk around Morro Bay, making room for a narrow corridor of electrical cables to connect offshore wind turbines to the onshore grid.

Environmental scientist Julia Kelly, who presented the commission’s staff report, explained that establishing the sanctuary in Morro Bay faced “significant opposition” from wind energy lease holders. They were concerned that it might limit their ability to lay these cables across the seafloor.

“While there has been discussion about establishing or expanding the sanctuary in this area once the wind cables are in place, NOAA has not yet identified the proposed sanctuary boundaries, and this addition or expansion is not discussed in the consistency determination,” she said.

But NOAA finds itself stuck between the wind and a hard place. The hard place is the more than 100,000 public comments they received on their draft environmental impact statement, many of which raise concerns over the exclusion of the Morro Bay area. Environmental groups worry that excluding the corridor would make it vulnerable to deep-sea mining or oil and gas drilling.

Why Not Both?

The wind developers and Chumash tribes are willing to collaborate, however. The Northern Tribal Council and Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians — who will co-manage the sanctuary with the state and NOAA — have expressed support for wind energy and are content with either excluding space for the cables or allowing them to run through a portion of the sanctuary.

Additionally, this month, Congressmember Salud Carbajal and Senator Alex Padilla wrote a letter to NOAA keeping with Carbajal’s track record of supporting a “Why not both?” approach. In it, the representatives suggest slicing the boundary into two phases, where Morro Bay is left out of the sanctuary for the installation of the cables, and then “grandfathered in” afterwards.

“As strong supporters of the [Biden] Administration’s goal of protecting 30 percent of U.S. oceans by 2030, we urge the Department of Commerce and NOAA to finalize the designation of the Chumash Sanctuary using this phased approach to establish robust protections for cultural and ecological resources off the Central Coast, while providing certainty for responsible offshore wind development, operations and maintenance,” the representatives wrote.

NOAA’s Michael Murray disappointedly mentioned, though, that retroactively expanding the boundary to include the cable corridor would not be automatic. The entire designation process — including public comment and environmental review — would need to be repeated, if regulations even allowed for the inclusion of the cables in the first place.

For now, NOAA is considering all boundary alternatives for the final designation, saying it would be “pre-decisional” at this stage in the process to outline a specific boundary.

“Despite these concerns and the lack of clarity on the final sanctuary boundary and management plan,” Kelly said, any of NOAA’s alternatives would be better than no alternative and “enhance marine biological resources and productivity, water quality and cultural resource protection.”

Fishing Fears

Others on Thursday questioned fishing restrictions. The voice of Tom Hafer, president of Morro Bay Commercial Fishermen’s Organization, echoed through the meeting space: “We keep hearing about all this protection; more protection, more protection. Does that mean protection from fishing? We already got enough MPAs [Marine Protected Areas] … I don’t think we need a sanctuary.”

Despite Hafer’s fears, no fishing regulations are being proposed — rather, regulations center on preventing pollution and prohibiting new oil, gas, and mining operations, according to NOAA.

“We’re supportive of clean waters and healthy habitat, and look forward to working together with the fishing industry in that area, because we do have a lot of shared goals,” Murray said.

‘An Essential Opportunity’

Though laden with uncertainty, sanctuary stakeholders — including environmental organizations the Sierra Club and the Environmental Defense Center — were all but jumping for joy after clearing the commission.

Next steps include publishing the final Environmental Impact Statement (expected in September) and solidifying decisions on the sanctuary’s boundaries and final management plan.

“This is a very important day for us,” said Violet Sage Walker, chair of the Northern Chumash Tribal Council.

Walker is the daughter and successor of former chair Fred Collins, who worked on the sanctuary nomination with environmental organizations for nearly a decade. Collins died in 2021, about a month before NOAA announced it would put the nomination forward as a designation.

While addressing the commission, Walker noted the overwhelming support the sanctuary has received throughout the designation process — including garnering more than 100,000 public comments and backing from thousands of Indigenous communities across the country.

“It’s an essential opportunity to uplift tribal collaborative management, to protect cultural resources, safeguard precious ecosystems and communities, and help foster sustainable relationships between people and the ocean,” Walker said. “We’re on the verge of having generations of hard work becoming a reality.”

Premier Events

Sun, Jan 11

3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mega Babka Bake

Fri, Jan 23

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Divine I Am Retreat

Sat, Jan 10

9:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Rose Pruning Day | Mission Historical Park

Sat, Jan 10

10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Ice Out For Good Santa Barbara

Sat, Jan 10

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Konrad Kono – Live in Concert

Sat, Jan 10

8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SB Improv: The Great Cornadoes Bake-Off

Mon, Jan 12

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Hot Off the Press: Junk Journal

Tue, Jan 13

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

✨ First Singles Social of 2026 | Open to All Ages 21+

Fri, Jan 16

9:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Eric Hutchinson at SOhO

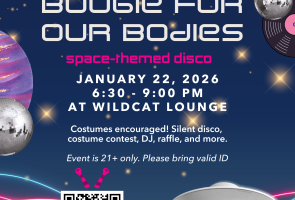

Thu, Jan 22

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Boogie for our Bodies

Sun, Jan 11 3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mega Babka Bake

Fri, Jan 23 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Divine I Am Retreat

Sat, Jan 10 9:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Rose Pruning Day | Mission Historical Park

Sat, Jan 10 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Ice Out For Good Santa Barbara

Sat, Jan 10 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Konrad Kono – Live in Concert

Sat, Jan 10 8:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SB Improv: The Great Cornadoes Bake-Off

Mon, Jan 12 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Hot Off the Press: Junk Journal

Tue, Jan 13 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

✨ First Singles Social of 2026 | Open to All Ages 21+

Fri, Jan 16 9:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Eric Hutchinson at SOhO

Thu, Jan 22 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.